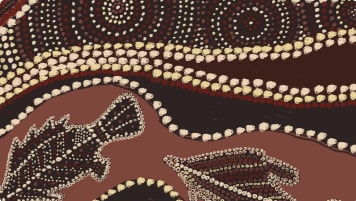

Understanding Aboriginal aquaculture

Aboriginal communities had the ability to harvest fish some 20,000+ years ago. Creating major centres of trade and cultural exchange, and supported permanent communities. Discover and learn more on a escorted small group package tour to Victoria, South Australia & Queensland for mature and senior travellers, couples and solo travellers interested in learning.

10 Jun 20 · 11 mins read

Understanding Aboriginal aquaculture

Aquaculture,‘the rearing of aquatic animals, or the cultivation of aquatic plants for food’ ( Oxford Dictionary ), was a major part of the pre-settlement economies of Aboriginal communities across Australia. Using weirs, dams, a stone fish trap, and other technologies, Aboriginal communities directed water to create a fish trap in order to ensure a consistent and abundant supply of fish. These aboriginal fish traps became major centres of trade and cultural exchange, and many supported permanent communities, challenging the myth that all Aboriginal people were hunter-gatherers.

As part of our new tours of Australia , Odyssey Traveller is offering clients the opportunity to visit two of the most extraordinary examples of Indigenous Australian aquaculture: the Brewarrina Fish Traps,that form the Brewarrina weir, visited on our tour of Outback Queensland ; and the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape , visited as part of our tour of the Southern States of Australia

Brewarrina Fish Traps, New South Wales

The heritage-listed traditional Aboriginal fish traps at Brewarrina consist of an elaborate network of rock weirs and holding ponds and pools arranged using river stones in an intricate way that allowed native fish to be herded and caught during both high and low river flows. Stretching for nearly half a kilometre along the Barwon river bed just below the Queensland border in north-west New South Wales, they are the largest group of aboriginal fish traps recorded in Australia.

Possibly the oldest man made structure on earth, the traps are estimated to be over 40,000 years old. According to Aboriginal tradition, the design of the traps was revealed when the ancestral creation dreamtime being Baiama threw his net over the Barwon river. With his two sons Booma-ooma-nowi and Ghinda-inda-mui he then built the traps to this design.

The incredible effectiveness of the stone fish trap of the indigenous people is testified to in the accounts of early settlers to Australia, who were amazed at how the aboriginal fish traps structure was able to withstand the regular Barwon riverfloods. A locking system using the river stones was engineered by the Aboriginal people, fixing the stone fish trap to the bed of the stream, while an arch and keystones contributed to its strength.

For the Aboriginal groups of Northern and Western NSW including neighbouring tribes , the stone fish trap and surrounds are extremely significant for their spiritual, cultural, traditional and symbolic meanings. The Ngemba people have long been the custodians of the aboriginal fishery, while the significance of the place is shared amongst various Aboriginalcommunity and peoples of Northern and Western NSW. A particular pond was managed by a family, but each family had responsibilities to others upstream and downstream to ensure the river hydrology and that all had secure provisions of fishecology.

It is likely that the Brewarrina weir stone fish trap supported a sedentary population. The poet Mary Gilmore reported her uncles as saying that 5,000 people lived around the Brewarrina fish traps. Alice Duncan-Kemp, the daughter of a pastoralist in southern Queensland, recalled that around 3,000 people lived on Farrar’s Lagoon, not far from Brewarrina.

Brewarrina was one of the great Aboriginal community meeting places of eastern Australia in outback NSW. Aboriginalhistory records huge numbers of indigenous people visited the brewarrina weir each year to attend the harvest, with the fish feast likely complemented with flour-based foods – bread or cake – indicated milled flour found by early European visitors to the area. The creation of the fish traps, and the laws governing their use, helped to shape the spiritual, political, social, ceremonial and trade relationships between various Aboriginal groups.

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, Victoria

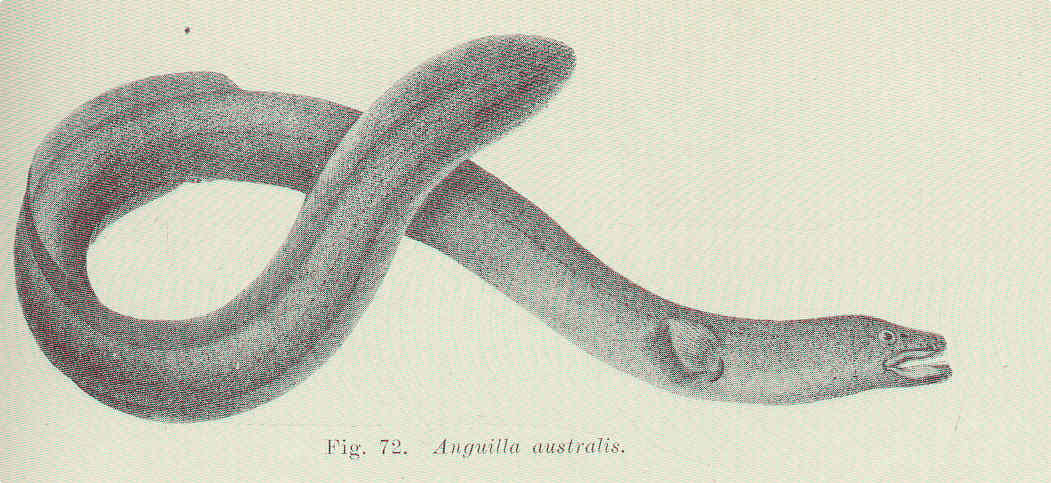

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is another complex aquaculture network, skilfully designed to catch the kooyang, or short-finned eel. It is located within the traditional country of the Gunditjmara Aboriginal people, in south-western Victoria, north of the Great Ocean Road. The site centres around the dormant volcano Budj Bim, formerly known as Mount Eccles. This landscape and associated eel farming is now a UNESCO World heritage site.

Budj Bim was formed by volcanic eruptions around 27,000 years ago. The volcano erupted several times, most recently around 7, 000 years ago, during which lava spread over 50 kilometres to the south, forming a network of lakes, ponds, and swamps – including Tae Rak (Lake Condah) and the Condah Swamp – rich in aquatic life.

From this, the Gunditjmara people created a complex set of eel traps, drawing upon their knowledge of the rise and fall of water levels, and of the geologic processes that shaped them. Using digging sticks, they dug shallow channels – some up to 200 metres long – into the rock, and built weirs and dams out of volcanic rock. By controlling the water, they were able to systematically trap, store and harvest kooyang. The Gunditjmara people also constructed long eel baskets, made of river reeds and steel grass, to regulate and trap the eels according to their size.

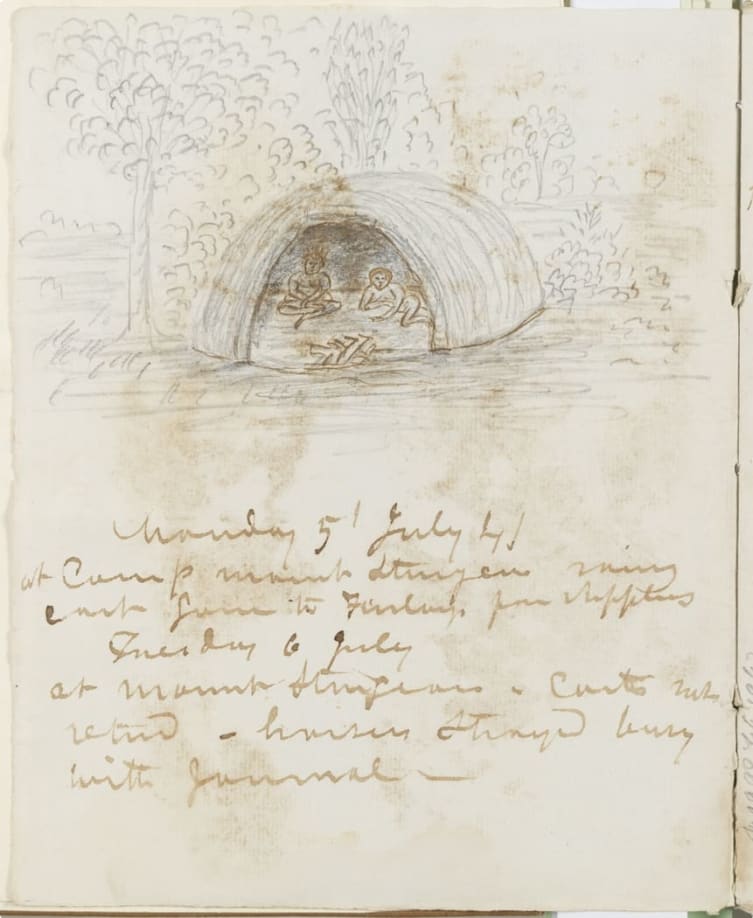

The scope of the eel traps is indicated by the 1841 journal of George Augustus Robinson, the ‘Chief Protector of Aborigines’ in Victoria, who wrote of:

an immense piece of ground trenched and banked, resembling the work of civilized man but which on inspection I found to be the work of the Aboriginal natives, purposefully constructed for catching eels.

Archaeologist Harry Lourandos suggested that the channels controlled the availability of eels. They distributed excess water during floods, retained water during drought, and directed eels to new parts of the country. Since eels flourished in ‘watercourses of this kind’, the channels likely increased the local eel population.

As UNESCO writes, ‘The highly productive aquaculture system provided a six millennia-long economic and social base for Gunditjmara society.’ A valuable commodity, the eels were traded with other Aboriginal language groups – including peoples as far away as New South Wales and South Australia – bringing prosperity to the Gunditjmara peoples. Though speared year-round, particular periods of abundance likely brought large numbers of people from around south-east Australia to join in the harvest.

Like Brewarrina, the eel traps likely supported a sedentary population. There is archaeological evidence of stone dwellings nearby. The existence of permanent settlements is also attested to both by early European explorers and settlers in the region and by the Gunditjmara people themselves. The structures are described by early colonists such as James Dawson and Aboriginal protector George Augustus Robinson. Residents of Lake Condah told Reverend Francis that prior to the arrival of Europeans they had lived in communities of forty or more, all living in the same hut. In the 1990s, archaeologist Heather Builth worked with the Gunditjmara people, who knew from oral history and tradition that the structures were houses – but whose insight had never previously been sought by researchers.

There appears to have been two forms of housing near Lake Condah: large structures where over fifty people gathered (testified to in Robinson’s reports and in oral tradition), and smaller dome-shaped houses, around three to five metres across and two metres high. When families had more children, extra rooms were added, or larger structures were subdivided with internal walls. The walls of houses were made out of basalt, with dome-shaped roofs either thatched by dense layers of grass or leaves, or by deep layers of earth. Doorways were closed with bark and timber doors. The houses often had an ancillary curving wall, providing extra protection from the wind, which appears to have also functioned as a kind of courtyard.

Sedentary structures appear to have been common in south-western Victoria. The Aboriginal Protector William Thomas recalled a village near Port Fairy, on the Southern Ocean coast, which had more than thirty houses, capable of accommodating between 200 to 250 people. Thomas recalled that:

there was on the banks of the creek between 20 and 30 huts of the form of a beehive, some of them capable of holding a dozen people. These huts were about 6’ high or (a) little more, about 10’ in diameter, an opening about 3’6” high for a door which was closed at night if they required with a sheet of bark, an aperture at the top 8” or 9” to let out the smoke which in wet weather they covered with a sod. These buildings were all made of a circular form, closely worked and then covered with mud, they would bear the weight of a man on them without injury.

Robinson observed that in times of abundance, such as the eel harvest, these ‘villages’ could be inhabited by up to 1000 people. In addition to trapping eels, they hunted birds and collected eggs, sowed and harvested cereals, tubers and fruits. The harvest was accompanied by ceremonial activities and ritual burning. It was a social occasion, on which people likely played competitive sports such as wrestling or marngrook, a football game played with a possum-skin ball which many historians believe influenced the development of the Australian Football League.

The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape is entwined with the cultural traditions of the Gunditjmara people, passed down through the generations by oral history and cultural practice. Budj Bim figures heavily in the Gunditjmara creation story. Thirty thousand years ago, their ancestors watched the eruption of the Budj Bim volcano, where the Ancestral Being, Budj Bim (‘Big Head’) transformed himself into the landscape. The Gunditjmara – like other Aboriginal peoples – have what UNESCO refers to as a ‘deep time’ conception of their society, which refers ‘to the idea that they have always been there.’

The first archaeologist to take an interest in the traps was Harry Lourandos, who, inspired by Robinson’s journals, brought a team of six students to investigate over the summer of 1974-75. He found that few people in the region were aware of the traps, and that little visual evidence remained. Noticing that while some archaeological sites in western Victoria dated back to the Ice Age, there was a stark increase in the number of sites dating to around 3000-4000 years ago, and even more in the last 2000 years. He interpreted this as evidence of significant social and economic changes, as people formed new exchange networks, moved into different environments, and lived increasingly sedentarily. In 1983, Lourandos suggested in a journal article that these transformations amounted to ‘intensification’. Archaeologists Caroline Bird and David Frankel have since challenged this framework, suggesting that the proliferation of more recent sites may be the result of preservation, rather than population increase.

A nation of aquaculture?

Across Australia, aquaculture was crucial to the lifeways of many Aboriginal groups. Knowledge of aquaculture was spread across the country alongside goods and culture. Jesse Hammond, a European settler described the fishing of weir by the Barragup people of the Serpentine River, Western Australia:

‘A wicker fence was built across the stream […] through this opening a race was constructed by driving two rows of parallel stakes in the riverbed. The bottom of the race was filled with bushes, until there was only about eight inches of clear water above the bushes for the fish to swim through. On either side of this race was built a platform, about two feet six inches below the top of the water. On these platforms the natives stood to catch the fish as they swam through the race.’

Near identical structures have been found near Purrumbete, western Victoria. Huge nets were used across the country to catch fish and crayfish, with the biggest reaching up to 270 metres long and taking almost three years to complete.

On the Glyde River, in Arnhem Land, the Yolgnu people developed a sophisticated system of fishing nets and traps. On a cane platform set into the river, they created large tubs made of paperbark, and sewed with cane. Chutes made out of paperbark brought water through the fence and into the tubs – where men stood waist deep in water, ready to collect the fish, which were now stranded on the bamboo platform.

Fishing and other forms of aquaculture was also an important component of the lives of Aboriginal peoples who lived by the coast. The Yuin people, near Eden, New South Wales, used their knowledge of fauna to construct a successful whale fishery. They developed ritualised interactions with killer whales, beginning with a ceremony in which a man would light two fires on the beach and pretend to limp between them, as if he was injured. The Yuin believed that this encouraged the whales to take pity, and bring the bigger whales into the bay for his use. Whatever the reason, the killer whales certainly herded bigger whales into the harbour, where they were driven into shallow water, and easily harvested by the Yuin – who would share the feast with the whales themselves. The practice is integrated into religious belief, with the Yuin believing that after death, they return as killer whales. After settlement, the Yuin incorporated European weaponry and boats into this practice, working alongside Europeans to serve the whaling industry.

The southern coast of Australia, from just south of Perth to Gippsland, Victoria, and north to Wollongong, as well as the coast of Tasmania, supported an economy based on crayfish and abalone (mutton fish) diving. Many communities lived sedentary or semi-sedentary lives on the basis of the harvest. In Victoria and Tasmania, diving for abalone was predominantly done by women, many of whom have been discovered to have an odd bone growth in the ear, developed to protect the ear from extreme cold (known as ‘surfer’s ear’). The fish were cooked in their shells on hot coals. After colonisation, Europeans boiled the fish, giving it a rubbery texture – but it turned out that abalone was a delicacy in China and Japan, cooked for only thirty seconds in a searing pan.

Odyssey Traveller explores the history of Aboriginal aquaculture on two of our new tours of Australia. Our tour of the Southern States of Australia takes you through the back country of Victoria, New South Wales, and South Australia. Designed to make you rethink the way you see southern Australia, our tour veers away from the major centres – Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide – in favour of little known sites that cast Australia‘s rich history in new light. In addition to the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, we visit another Aboriginal World Heritage Site – Mungo Lakes National Park, where the remains of Mungo Man and Mungo Lady were found, dating Aboriginal settlement of Australia back 40, 000 years or more. This tour also heads to the quirky outback city of Broken Hill, to the regional city of Mildura, and to Burra, a historic mining town in South Australia.

We visit the Brewarrina Fish Traps as part of our tour of outback Queensland. Staying away from tourism Australia classics, Brisbane, the Gold Coast and the Great Barrier Reef, our tour takes you through quintessential outback Australia territory of central Queensland. We visit the historic towns of Longreach and Barcaldine, and witness the ancient footprints of dinosaurs preserved deep in the desert, on a day tour from Winton.

Travellers with an interest in Aboriginal culture and history should also check out our tour of the Flinders Ranges, in which we visit the culturally important Wilpena Pound while exploring the spectacular scenery and wildlife of central Australia, and our trip to the Kimberley, Western Australia, which sees ancient Aboriginal art among some of the Australian outback’s most remote country.

Every Odyssey Traveller Australia tour is designed for mature and senior travellers, who seek an authentic experience of their destination. We have specialised in bringing Australian travellers to the world since 1983.

Our tours cover a range of interests. In Adelaide, we learn about the Arts and Crafts heritage of the Adelaide Hills, the South Australian wine industry at the Barossa Valley and McLaren Vale, and visit unspoilt Kangaroo Island. On our tour of Tasmania we explore rugged landscapes and stunning coastline, and explore the history of the island as a penal colony. We explore the incredible Western Australian wildflowers, the result of ancient geological processes. And in Victoria, we learn about 19th century expansion and decline on the elegant Victorian streets of Melbourne, Ballarat, and Echuca, by the Murray River.

Every Odyssey guided tour is led by an expert tour guide, chosen for their local knowledge. We move in small groups of around 6-12 like-minded people.

Articles about Australia published by Odyssey Traveller:

- The Kimberley: A Definitive Guide

- Uncovering the Ancient History of Aboriginal Australia

- Aboriginal Land Use in the Mallee

- Mallee and Mulga: Two Iconic and Typically Inland Australian Plant Communities (By Dr. Sandy Scott).

- The Australian Outback: A Definitive Guide

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.

External articles to assist you on your visit to Australia:

- UNESCO: Budj Bim Cultural Landscape and Willandra Lakes Region

- Finding Mungo Man: the moment Australia’s story suddenly changed

- A 42,000-Year-Old Man Finally Goes Home

- Fish traps and stone houses: New archaeological insights into Gunditjmara use of the Budj Bim lava flow of southwest Victoria over the past 7000 years

- ‘A big jump’: People might have lived in Australia twice as long as we thought

- Mildura, Victoria

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Australians and Traditional Custodians of the lands where we live, learn and work. We pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

Selected small group package Tours of Australia

days

Mar, Apr, May, Jul, Aug +2Small group tour of outback Queensland

Visiting New South Wales, Queensland

To Dubbo and back, this small group tour takes you to learn about the Brewarrina fish traps, we travel high up into North Queensland to see the Dinosaurs of Winton and incredible Aboriginal rock art at Cathedral gorge and learn about opal mining and the history of Lightning ridge.

days

Mar, May, Aug, Sep, Oct +2Small group tour of World Heritage sites and more in the Southern States of Australia

Visiting New South Wales, South Australia

Discover the World Heritage Sites of the southern states of Australia travelling in a small group tour. A journey of learning around the southern edges of the Murray Darling basin and up to the upper southern part of this complex river basin north of Mildura. We start and end in Adelaide, stopping in Broken Hill, Mungo National Park and other significant locations.

13 days

Mar, OctSmall group tour; Broken Hill and back

Visiting New South Wales, Queensland

Small group tour of New South Wales, Queensland & South Australia deserts, from Broken Hill. Learn about the history of the people who explored the deserts, from indigenous communities to Europeans, as well as Burke and Wills, visit White Cliffs, Birdsville, Maree.

From A$11,550 AUD

View Tour

15 days

Sep, Dec, Jan, Feb, Mar +2Eyre & Yorke Peninsulas, and the Gawler Ranges

Visiting South Australia

Small group tour South Australia. Yorke, Eyre, and Gawler Ranges, discover the local history.

From A$10,350 AUD

View TourArticles about Australia

Australia’s Ocean Frontier: Exploring the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia

Learn about the landscape and the recent settlement of this Peninsula on the South Australian coast. To see and learn more join on the this collection of Australian small group package tours for mature and senior travellers, couples or singles or join the Eyre & York peninsula program.

Budj Bim Cultural Landscape, Victoria

Article for escorted small group tour about this program visiting UNESCO World Heritage sites in Victoria, South Australia & NSW. Exploring and learn about Budj Bim cultural landscape for mature and senior travellers .

Mungo Man and Mungo Lady, New South Wales

Part of a small group tour of World heritage sites on Victoria, NSW & South Australia for mature and senior travellers. Learn and explore in the Mungo National park about Aboriginal settlement and the fauna and flora of this National park.

Uncovering the ancient history of Aboriginal Australia

For small group escorted tours of Australia in Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, Tasmania, Western Australia and the Northern Territory a guide on Aboriginal culture for mature and senior travellers.

Aboriginal history and culture of Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory

For those seek to learn as they travel then the history of the Aboriginal journey and timelines that unfold as a discovery in Australia seek to fascinate the mature and senior traveller on a small group package tour for couples and singles. From Darwin, this tour also visits Arnhem land as well as Kakadu, during the dry season.

Aboriginal Sites of Importance in Outback Queensland, Australia

Outback Queensland is hiding a number of unforgettable indigenous experiences on this small group tour for senior travellers. Especially at the Brewarrina Fish Traps, and Carnarvon Gorge, for example where you can experience and learn about dreamtime creation stories, age-old cultural practices and traditions, and Aboriginal art.