Britain: The First Industrial Nation

Britain: The First Industrial Nation In the mid-18th century, the Industrial Revolution was largely confined to Britain. Historians and economists continue to debate what it was that sparked the urbanisation and industrialisation that would change…

12 Feb 19 · 8 mins read

Britain: The First Industrial Nation

In the mid-18th century, the Industrial Revolution was largely confined to Britain. Historians and economists continue to debate what it was that sparked the urbanisation and industrialisation that would change humanity’s way of life, for better or for worse. Some say it was less of a “revolution” and more of a “slower, incremental” process that led to Britain accounting for nearly a quarter of global industrial production in the 19th century, with British workers becoming the richest men and women in Europe. Others say England’s incredible economic growth was financed by imperialism, a transformation built on the suffering of other nations and its own citizens. To quote Robert Tombs, “If it made England what Disraeli called ‘the workshop of the world’, it did so by means of William Blake’s ‘dark, satanic mills’, squalid towns, and a degraded and exploited workforce” (The English and Their History, 2014, p. 369), a belief that persists to this day, evident in English nostalgia for the countryside and “pre-industrial arcadia” (Tombs, p. 369).

The Industrial Revolution produced many and far-reaching changes, among them:

- use of new materials (iron and steel)

- use of new energy sources (coal, steam engine, electricity, fossil fuels)

- new inventions that enabled mass-production

- rise of the “factory system” involving division of labour and specialisation

- growth of cities

- developments in communication and transportation

- decline in the importance of land as source of wealth

According to Tombs, Britain’s economic transformation can be traced further back, back before the age of coal and steam, to the Black Death of the agrarian middle ages.

The Black Death and Agriculture

The Black Death looms large in the modern imagination, with grim images of the dead lining the streets of Europe. In the early 1340s, rumours of a “Great Pestilence” devastating Asia had circulated among Europeans, until the rumour became reality with the arrival of 12 ships from the Black Sea at the Sicilian port of Messina in October 1347. Most of the sailors aboard the 12 ships were dead; those still living were covered in boils. Sicily turned the ships away, but it was too late.

Historians believe the Black Death was brought by the bubonic plague (though this is still being debated) which we now know is spread by a germ called Yersina pestis that could be transmitted through the air or through the bite of infected rats. Medieval Europe knew little about disease transmission and had no means to stop it. The Black Death would reach London by 1348, and over the next five years would kill a third of Europe’s population.

European society in the 14th century was incredibly dependent on the soil: nine out of 10 people worked in agriculture. The Black Death’s high mortality rate decimated the agricultural labour pool, which afforded the peasant class an ironic silver lining–people were dying left and right, but fewer workers also meant less competition. The surviving workers could demand (and indeed demanded and received) higher nominal wages. According to David Routt in “The Economic Impact of the Black Death”: “Wages in England rose from twelve to twenty-eight percent from the 1340s to the 1350s and twenty to forty percent from the 1340s to the 1360s.” Rural workers now also had leverage to demand better working conditions, compared to their standing in the pre-plague era, when the landed elite held all the cards and workers acquiesced to demeaning tenure at a lord’s manor in order to survive.

Hence the Black Death brought devastating loss of lives, but also the improvement of wages and a higher standard of living for the lowly English peasant. Routt also mentions the psychological impact of the plague–hounded by the spectre of death, individuals with disposable income turned to the pursuit of pleasure via consumerism; that is, the purchase of luxury goods. This psychological mindset also appeared in England in the late 1600s, an appetite for novel and exotic goods that spurred an eagerness to work more in order to earn more and have more money to gratify hedonistic needs (Tombs, p. 371).

England maintained the high living standards even after population rose following the Black Death by diversifying its economic activities (Tombs, p. 370). The landowning elite shifted to sheep-raising and other forms of livestock husbandry, which were less labour-intensive than traditional grain agriculture. Sheep-raising gave rise to the export of wool. With access to abundant raw material, England was exporting 40,000 pieces of woollen cloth by the year 1400 .

Textile and the Industrial Revolution

“Clothing was the spearhead of the Industrial Revolution,” declares Tombs. Wool, England’s major source of wealth until the 18th century, was produced by a literal “cottage industry“: a network of locals working from their homes to supplement their earnings from farming. This was how goods were produced before the advent of factories: food, clothes, furniture, and other necessities were made at home or by skilled artisans in small-scale production.

But soon cotton, a hard-wearing fabric made from raw materials imported from the United States, grew in popularity. The increasing demand for the fabric inspired English inventors to find ways to speed up the labour- and time-intensive process of cleaning and spinning raw cotton into cotton thread.

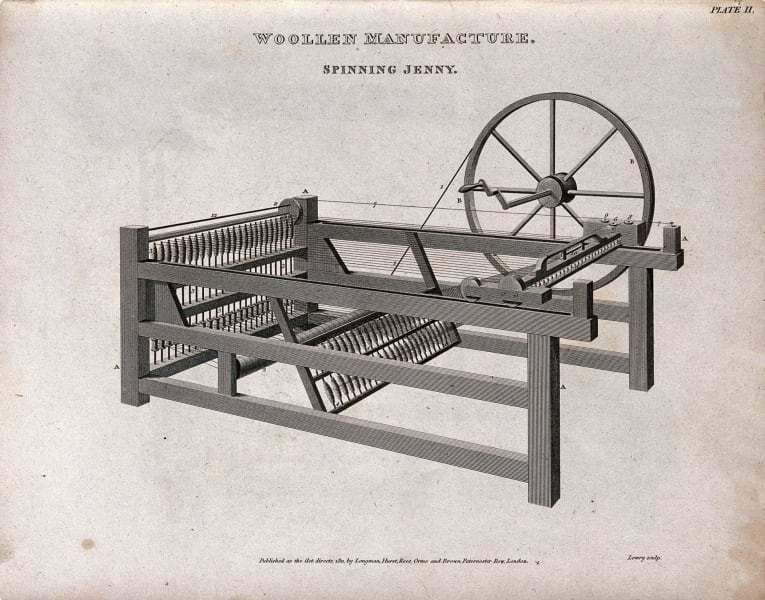

Around 1764, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, which could spin eight spindles at the same time (and hence produce eight spools of thread). Hargreaves’ invention, patented in 1770, would be improved by later inventors. In the 1780s, Edmund Cartwright developed the power loom, which mechanised weaving.

These machines demanded more space than a single household could ever provide. “Manufactories” (later, “factories”) were built to house the contraptions and the workers who would oversee them.

Innovations in steam technology also marked the shift from the old power sources of waterwheels, windmills, and horsepower to coal-powered steam engines. The steam engines also provided power to the factories and brought innovations to transportation, making it possible to travel from London to Bristol in a matter of hours rather than days.

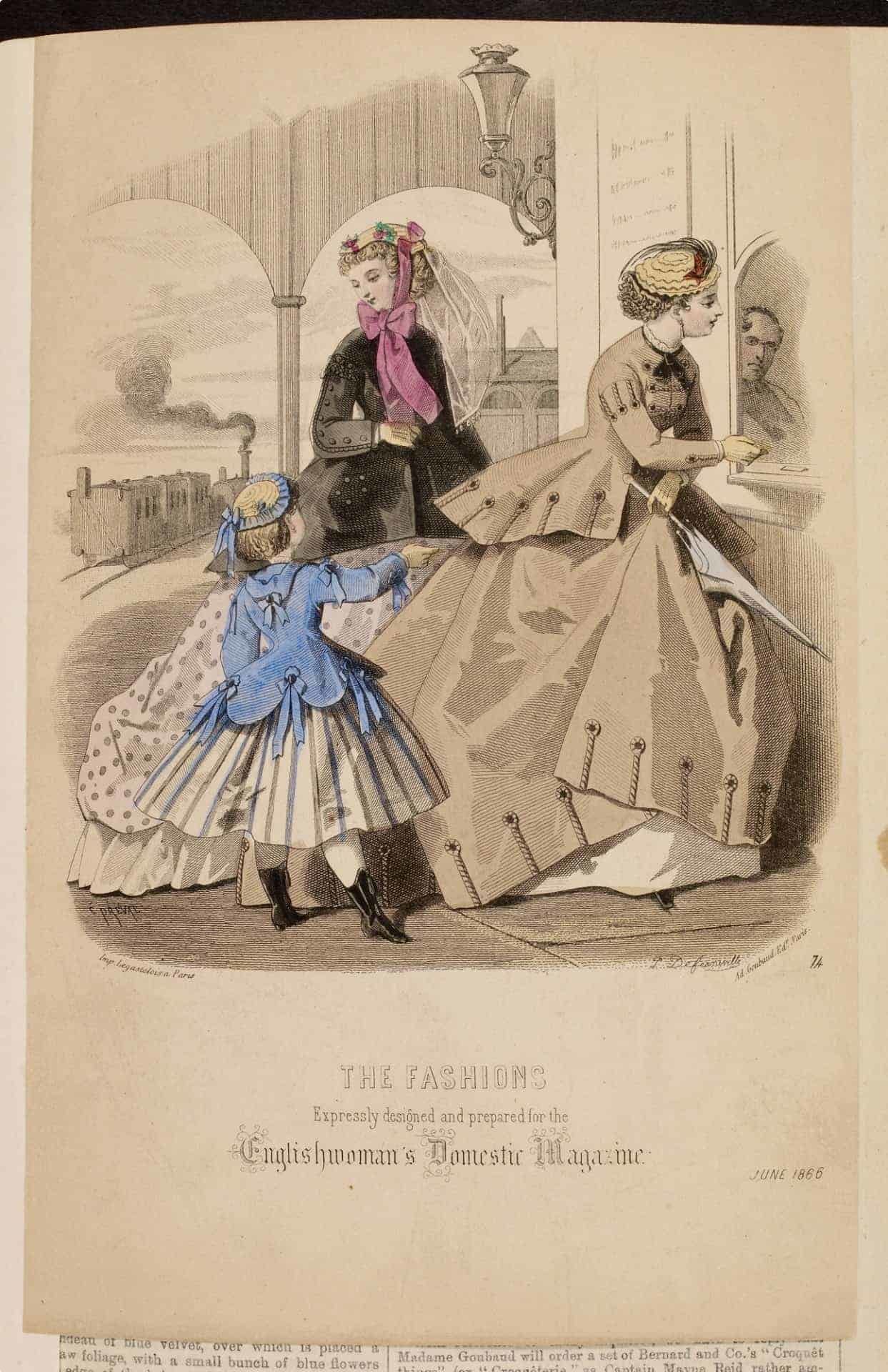

The British Empire by the 1880s had reached the Far East, bringing wealth to industrialists and merchants, and expanding the middle class, giving them power and confidence that for centuries was seen to belong only to the aristocracy. The new British middle class displayed their social standing and fortune through the clothes they wore and the goods they acquired for their household. (Read more about the Industrial Revolution and Victorian-era fashion.)

Britain and Her Neighbours

By 1760, England’s income per capita was higher than India’s in 2000 (Tombs, p. 371), which draws a picture of the staggering wealth of the English.

England had a headstart compared to its neighbours due to its having a politically stable society. While Britain was laying down more tracks for its steam locomotives, France was dealing with a Revolution, an unstable political situation that discouraged large investments in industry. Germany had vast resources of coal and iron, but was busy working towards national unity (achieved in 1870).

Efforts to modernise Russia were rarely embraced by Russia’s landowning aristocracy, who derived their wealth and privilege from the labours of serfs who toiled on their land, and saw no personal gain in transitioning from agriculture to new forms of industry. Russia would only begin building the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1891. (Read more about it here.)

Legacy of Industry

Machine manufacturing and the mass production of goods led to an increased supply and a decline in cost, allowing more people to buy more items that enhanced their quality of life. “Common” people–or those who did not belong to the aristocracy–were able to save money and build personal wealth. Ownership of land was no longer as important as it was in the age of the agrarian economy. In the age of machines, a person could move to the city, find employment in a business, and save and invest a portion of his wages.

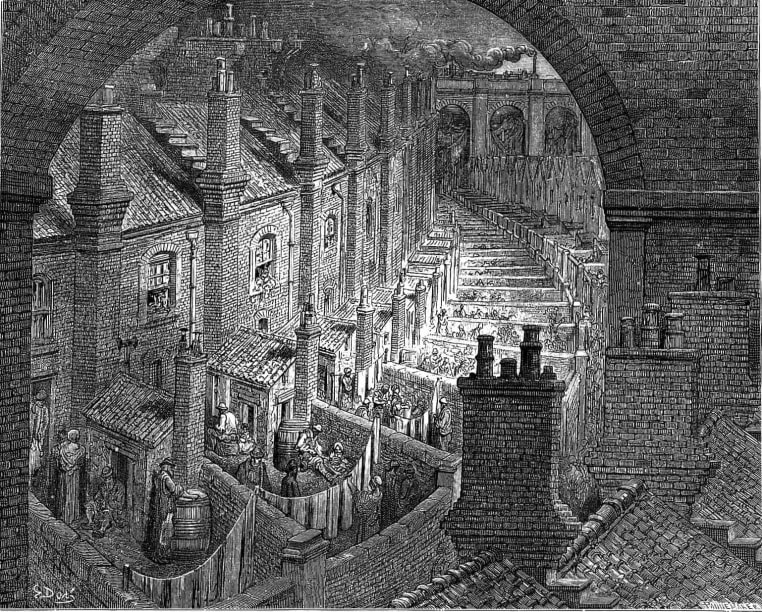

However, the age of machines also put more emphasis on efficiency and profit than on the safety of human beings. Child labour was rampant. Richard Arkwright’s cotton factories employed nearly 600 people by the 1770s, including many small children. In the early 1860s, an estimated one-fifth of the workers in Britain’s textile industry were younger than 15. Factory labourers often worked 14–16 hours per day, six days a week, for low wages in unsafe working conditions.

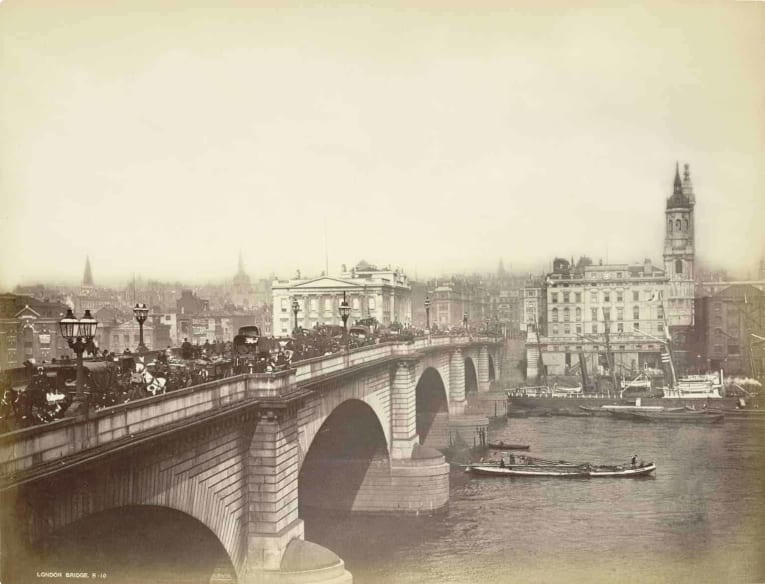

The mass migration of people from the countryside to urban areas resulted in overcrowded housing, pollution, and unsanitary, disease-ridden living conditions. London was a city of 750,000 people by the mid-18th century, and was filled with factories that burned coal and blanketed its buildings with soot.

Prosperity also had negative impact on English health, with the higher consumption of alcohol, tobacco, sugar, and meat (Tombs, p. 380), increased stress, and the adoption of a sedentary lifestyle.

Working and living conditions improved with new government regulations and the rise of the trade unions in the later part of the 19th century. By this time, the Industrial Revolution had spread to other parts of the globe.

Its effects, good and bad, can still be felt to this day. In clothes manufacturing, for example, production capacity and jobs in the textile, clothing, and footwear (TCF) industries, in pursuit of cheap labour and higher profit margins, had shifted from Europe and North America to Asia and other parts of the Global South. There was also a parallel shift in production from the formal to the informal sector, where workers received low wages and had poor working conditions. Global production now exceeds 100 billion garments a year, negatively impacting the environment and workers’ rights in the countries where these garments are produced. (Read more here.)

According to Professor Tony Wrigley, the Industrial Revolution “was also the point at which society ceased to depend on the land, which can produce indefinitely, and moved to dependence on energy sources, which could support vastly increased production but were certain to become exhausted.”

Many countries are now advocating a shift to renewable energy sources, such as solar, geothermal, and wind energy, which are more sustainable. There has also been an increasing call for “slow fashion” or “slow living“, a return to “pre-industrial arcadia”, the specific creativity of artisans, and small-scale production that the machines and factories have replaced 200 years ago.

If you want to learn more about Britain and the Industrial Revolution, consider joining Odyssey Traveller’s Queen Victoria’s Great Britain tour.

This 21-day small group program provides participants with talks and short lectures from a group of guides with expertise on Victorian Britain. The tour commences in London and concludes in Glasgow.

In Odyssey Traveller’s Exploring Britain through its Canals and Railways tour we visit the key sites associated with the history of the railway and canal systems. We travel from the midlands of England and North Wales, up the west coast to Scotland, before returning down the east coast to London. Our small group tours include an experienced guide to provide context and access to locations off the beaten track. For more information on all of our tours to the British Isles, click here.

About Odyssey Traveller

Odyssey Traveller is committed to charitable activities that support the environment and cultural development of Australian and New Zealand communities. We specialise in educational small group tours for seniors, typically groups between six to 15 people from Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada and Britain. Odyssey has been offering this style of adventure and educational programs since 1983.

We are also pleased to announce that since 2012, Odyssey has been awarding $10,000 Equity & Merit Cash Scholarships each year. We award scholarships on the basis of academic performance and demonstrated financial need. We award at least one scholarship per year. We’re supported through our educational travel programs, and your participation helps Odyssey achieve its goals.

For more information on Odyssey Traveller and our educational small group tours, visit and explore our website. Alternatively, please call or send an email. We’d love to hear from you!

Related Tours

23 days

Oct, Apr, SepCanals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of Wales, Scotland & England that traces the history of the journey that is the Industrial revolution. Knowledgeable local guides and your tour leader share their history with you on this escorted tour including Glasgow, London, New Lanark & Manchester, Liverpool and the Lake district.

From A$18,750 AUD

View Tour

23 days

AprAgrarian and Industrial Britain | Small Group Tour for Mature Travellers

Visiting England, Wales

A small group tour of England that will explore the history of Agrarian and Industrial period. An escorted tour with a tour director and knowledgeable local guides take you on a 22 day trip to key places such as London, Bristol, Oxford & York, where the history was made.

From A$17,275 AUD

View Tour

6 days

Apr, SepLondon Short Tour

Visiting England

A small group tour of London is a collection of day tours that visit and explore through the villages of the city. This escorted tour includes a journey out to Windsor castle. We explore Contemporary and learn about Roman Walled city, Medieval, Victorian London and the contemporary city today.

From A$7,345 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Sep, JunQueen Victoria's Great Britain: a small group tour

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of England that explores the history of Victorian Britain. This escorted tour spends time knowledgeable local guides with travellers in key destinations in England and Scotland that shaped the British isles in this period including a collection of UNESCO world heritage locations.

From A$16,675 AUD

View Tour

From A$14,595 AUD

View TourRelated Tours

23 days

AprAgrarian and Industrial Britain | Small Group Tour for Mature Travellers

Visiting England, Wales

A small group tour of England that will explore the history of Agrarian and Industrial period. An escorted tour with a tour director and knowledgeable local guides take you on a 22 day trip to key places such as London, Bristol, Oxford & York, where the history was made.

From A$17,275 AUD

View Tour

23 days

Oct, Apr, SepCanals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of Wales, Scotland & England that traces the history of the journey that is the Industrial revolution. Knowledgeable local guides and your tour leader share their history with you on this escorted tour including Glasgow, London, New Lanark & Manchester, Liverpool and the Lake district.

From A$18,750 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Sep, JunQueen Victoria's Great Britain: a small group tour

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of England that explores the history of Victorian Britain. This escorted tour spends time knowledgeable local guides with travellers in key destinations in England and Scotland that shaped the British isles in this period including a collection of UNESCO world heritage locations.

From A$16,675 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Apr, AugSeven Ages of Britain, snapshots of Britain through the ages.

Visiting England, Scotland

This guided small group tour starts in Scotland and finishes in England. On Orkney we have a day tour to the UNESCO World heritage site, Skara Brae, before travelling to city of York. Your tour leader continues to share the history from the Neolithic to the Victorian era. The tour concludes in the capital city, London.

From A$16,895 AUD

View Tour

From A$14,595 AUD

View Tour

20 days

May, Sep, JunWalking Ancient Britain

Visiting England

A walking tour of England & the border of Wales. Explore on foot UNESCO World Heritage sites, Neolithic, Bronze age and Roman landscapes and the occasional Norman castle on your journey. Your tour director and tour guide walk you through the Brecon beacons, the Cotswolds and Welsh borders on this small group tour.

From A$14,725 AUD

View Tour