Early Russian History and its Key Figures

Early Russian History and its Key Figures It is probably unsurprisingly that the largest country in the world, encompassing Eastern Europe and Northern Asia, with its ever-changing landscapes, multiple timezones and diverse inhabitants, would also…

5 Dec 19 · 23 mins read

Early Russian History and its Key Figures

It is probably unsurprisingly that the largest country in the world, encompassing Eastern Europe and Northern Asia, with its ever-changing landscapes, multiple timezones and diverse inhabitants, would also have a long and complex history. Early Russian history begins in the late 9th century with the establishment of the Rus state and from this point on, there are many twists and turns in the story of Russia. There are the early Mongol invasions, Ivan the Terrible and tsarists regimes accompanied by the conquering of foreign lands and the ages of enlightenment followed by bloody revolutions and destructive wars.

Russia’s history is turbulent, dramatic and violent but for a history enthusiast it is also gripping and engrossing. While there are many household names from Russia’s modern history, such as Rasputin, Trotsky and Gorbachev, there are some equally compelling and significant figures in early Russian history, like Rurik of Rus, Ivan the Great and of course, Ivan the Terrible.

In this article, we will delve into early Russian history and its key characters to gain a deeper understanding of the Russia we know today. Some of these figures have shaped the nation of Russia in consequential ways and both enriched and enfeebled different aspects of the state. This is the first article in a series of articles that will explore Russian history and its characters, from the foundation of the Rus state up until Vladimir Putin.

This article is inspired by Martin Sixsmith’s book Russia: A 1000-Year Chronicle of the Wild East (Penguin House 2011) as well as other resources linked throughout. The article acts as a backgrounder for Odyssey Traveller’s small group tours that travel to Russia and those interested in the history of Eastern Europe.

Currently, Odyssey Traveller offers five tours to Russia. The tours, usually involving travel by the Trans-Siberian rail across the vast country, visit St Petersburg and Moscow as well as other key sites such as Irkutsk and Lake Baikal. Travellers will get the chance to see some of the country’s main tourist attractions including Peterhof Palace, Nevsky Prospekt, the Moscow Kremlin and Lenin’s Mausoleum.

For our full list of tours travelling to Russia, please click here.

The Land of the Rus

Archaeological evidence suggests that Indo-European, Ural-Altaic and other diverse groups occupied the area that is now Russia since 2 millennium BCE. Little is known about this period and the institutions and activities of those who populated the territory. From the 3rd century, the East Slavs emerged as a coherent group in this part of Europe. The story of how various Slavic tribes came to unite under one leader is retold in The Russian Primary Chronicle (also known as Nestor’s Chronicle and Kiev Chronicle). The Russian Primary Chronicle, thought to have been written in 1377, covers Russian history from the year 852 to the second decade of the 12th century and has been of fundamental importance to understanding this time period, thanks to several surviving editions.

Novgorod (known as Veliky Novgorod) is often called the birthplace of Russia as it is considered the oldest city in the country. Prior to the 9th century Novgorod was an important staging post on the trade route that ran from the Baltic Sea in the north down to the Byzantine Empire in the south. It was here that various Slavic tribes lived, with each tribe vying for power over the others. According to The Primary Chronicle, ‘tribe rose against tribe’ with the discord between the groups quickly intensifying to war. However, before any destruction ensued, the tribes said to one another ‘Let us seek a prince who may rule over use and judge us according to the law’. In a time period marred by wars and invasions, this decision to seek a negotiated settlement was truly remarkable.

The tribes decided to find a neutral leader from outside the region to rule over them and went overseas to the Vikings to pick one out. As the story goes, the Slavic tribes found a group of Vikings called Rus (as others were called Swedes and Angles) and told them of their rich but disorderly land and asked three brothers to come and reign as princes. The eldest brother, Rurik of Rus, located himself at Novgorod and the Russian land gained its name. The date that Rurik arrived in Novgorod, 862 AD, is generally regarded as the founding of the Russian nation.

Rurik of Rus

Rurik of Rus has almost mythological status in Russian history and is considered by many Russians to be the founder of the first Russian dynasty and the true creator of Russia. There is some dispute among historians whether he really existed or was some amalgamation of Viking princes who came and ruled in the area. However, for many Russians, Rurik, real or not, is an important figure and symbolic of the transition from disparate, warring tribes to something that resembled a nation or community.

Rurik was a Varangian chieftain but little is known about his birthplace, family history or early life. Some 19th-century scholars theorised he may have been Rorik of Dorestad, a Danish Viking who died around 882 but there is not much concrete evidence to confirm this. Most historians agree Rurik and his followers likely originated from Scandinavia and were related to Norse Vikings.

According the Primary Chronicle, Rurik and his brothers Sineus and Truvor and their large retinue came to the area that is now Russia between 860-862. Sineus claimed an area at what is now Belozersk, near Lake Beloye, while Trevor established himself at Pskov. Rurik first residence was allegedly in Ladoga but he moved his seat of power to Novgorod. When Sineus and Truvor both died shortly after establishing their territories, Rurik consolidated their land into his territory. He remained in power until his death (reportedly 879). It is said that on his deathbed, he declared Oleg his successor and entrusted Oleg with his son Igor, who was still too young to rule.

During this time, the Rus gained a reputation for ferocity and aggression with tales in the Chronicle outlining how Rurik’s men led expeditions to Byzantine Empire, south of Rus territory, killing many Christians and laying siege to Constantinople. Rurik’s successors would eventually move the capital to Kiev, founding the state of Kievan Rus. It is said that a number of extant princely families are descended from Rurik but the last Rurikid who would rule Russia was Vasily IV.

Oleg of Novgorod

Oleg is thought to have been the brother-in-law of Rurik and agreed with Rurik’s death to take care of both his kingdom and his son, Igor. During his rule, Oleg seized control of new territories including the Dnieper cities. In 883 he gained power of Kiev by supposedly tricking and killing Askold and Dir, the military men who ruled the city. Oleg named Kiev the capital of Kievan Rus, his newly created state and set to work fortifying the city and ordering military expeditions around the area to neutralise any potential threats around the area.

In 911, Oleg set his sights on Constantinople and ordered 80,000 men in 2,000 boats to sail down the Dnieper and besiege the city. Terrified of what Oleg might do, the Greeks agreed to negotiate with him and give him anything he wanted in return for keeping their city. As a result, the Russians were able to negotiate a very favourable trade treaty with the Greeks that helped to lay the foundations of Kiev’s future prosperity. Russians would travel to Constantinople with goods and slaves to trade and return to Kiev bearing wine, glassware, jewellery and silks. The capture of Kiev thus would lead to the Kievan Russians travelling the world, building an economy and seeking out new territory to conquer.

In the Primary Chronicle, Oleg is often called the Prophet. Legend has it that Oleg’s death was prophesied by pagan priests who said that Oleg’s stallion would cause his death. In order to defy the prophesy, Oleg had the horse sent away and when he discovered the horse had died, he asked to see its remains. While visiting the bones, he touched the horse’s skill with the tip of his boot, causing a snake to emerge from inside the horse’s skull. The snake bit Oleg and he died, fulfilling the prophecy.Vladimir the Great

Vladimir the Great or Vladimir I was the Grand Prince of Kiev and the ruler of Kievan Rus from 980 to 1015. He is best known for changing the state religion to Orthodox Christianity and Christianising the Kievan Rus. For this, he was made a saint after his death.

Vladimir was the illegitimate son of Prince Sviatoslav of the Rurik dynasty. His mother was his father’s housekeeper, Malusha Malkovna and in Norse sagas she is described as being a prophetess who lived to the age of 100 and was brought from her cave to the palace to predict the future.

While Vladimir was made Prince of Novgorod in 970, his father’s legitimate son, Yaropolk, was given control of Kiev. After the death of his father in 972, Vladimir fled to Scandinavia where he recruited a Varangian army and then returned to Kiev and conquered it, killing Yaropolk and becoming ruler of all of Kievan Rus. By 980, he had consolidated the Kievan realm from Ukraine up to the Baltic Sea.

When he came to power Vladimir was a pagan, who was said to have had seven or eight wives and taken part in idolatrous rites including human sacrifice. Initially when in power, he built pagan temples and icons around Kiev. However, according to the Primary Chronicle, in 987, Vladimir sent envoys out to study the religions of neighbouring nations as many of the leaders of these nations had been encouraging Vladimir to adopt their respective faiths. The envoys returned and reported that of the Muslim Bulgarians of the Volga, there is no gladness among them and that the lack of alcohol made it undesirable as a religion for the Russians. It is often said that on this point, Vladimir remarked ‘Drinking is the joy of all the Rus. We cannot exist without that pleasure’. It was Eastern Orthodox Christianity that most impressed the envoys who were dazzled by the Byzantine Church, describing to Vladimir the overwhelming beauty of the majestic Divine Liturgy at Hagia Sophia.

Consequently, in 988, Vladimir sought the hand of Emperor Basil II’s sister, Anna. Never before had a Byzantine imperial princess married a Slavic pagan but the Emperor needed military aid from Vladimir and so a pact was formed. Basil II consented to the marriage, under the condition that Vladimir become Christian. After his baptism, Vladimir took on the Christian name Basil and ordered the Christian conversion of Kiev and Novgorod. Pagan idols were cast into the Dnieper River. In their place, Christian churches were built including one dedicated to St. Basil and the first stone church in Kiev, the Church of Tithes, built in 989.

Alexander Nevsky

St. Alexander or Alexander Nevsky is a key figure of medieval Rus and recognised for his military victories over German and Swedish invaders. He was canonised as a saint in 1547.

During his lifetime, Nevsky served as Prince of Novgorod, of Kiev and of Vladimir, one of the medieval capitals of Russia. While the Grand Prince of Kiev was considered to be the supreme ruler of Kievan Rus, the city states were led by individual princes who had their own armies. Nevsky was the second son of Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich and his grandfather was Vsevolod the Big Nest, the Grand Prince of Vladimir who brought glory to the city.

In 1236, the Novgorodians summoned Alexander to become prince of Novgorod in the hopes he would defend their position in the northwest from Swedish and German invasions. In 1240, at just nineteen, Nevsky successfully attacked and defeated the Swedes and prevented Novgorod from invasion. The following year, the Teutonic Knights, a militarised group of Prussian crusaders, sought to invade Rus and spread the Catholic faith. The knights captured Pskov but as they marched on to Novgorod, the now-20-year-old Nevsky was ready to meet them. Legend has it that, even with a growing number of Russian casualties, Nevsky managed to lure the enemy forces onto the thin ice of the Lake Peipus where they went crashing through the ice into the chilly waters to meet their deaths. This became known as the Battle on the Ice.

This was an important victory and is still seen a a significant event of the Middle Ages. It was unheard of at the time that foot soldiers could defeat mounted knights but this was precisely what Nevsky and his soldiers did and thus it represented an important milestone for Russia.

After the victory, Nevsky proved himself to be quite a politician. He sent envoys to Norway and arranged a peace treaty that was signed between Rus and Norway in 1251. However, in the east of the country another problem was arising. Mongol armies were conquering parts of Rus and Nevsky’s father had agreed to serve the new Mongol rulers. When he died in 1246, the throne of the Grand Prince was left vacant but it was Nevsky’s younger brother, Adrei or Andrew, was installed as Grand Prince by the Great Khan. In 1252, Adrei refused to pledge allegiance to the new Great Khan and he was driven out of Russia. In his place, Alexander became Grand Prince.

Despite facing opposition from the people, Nevsky continued the policy of cooperating with the Mongols and for his cooperation, he was allowed considerable freedom in how he ruled and received major concessions from the Mongol khans. While Nevsky had to pay tribute to the Mongols, he could essentially act as a deputy of them. Nevsky worked to restore Rus’ prosperity and when he died in 1263, he was greatly admired as a leader. He is remembered in Russian history for his deeply felt Christianity, his military prowess and his ability to co-exist with the Mongols.

However, the invasion of the Mongols saw the last remnant of Kievan power destroyed. Medieval Russia was essentially divided into four regions and the Khan of the Golden Horde would rule European Russia until 1480.

In 1938, the famous Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein made the film Alexander Nevsky, depicting the Battle of the Ice. The epic film was made in a politically charged context, against the backdrop of the rise of Nazi Germany, and the film is noted for its Stalinist propaganda. However, the Battle on the Ice scene continues to be one of the most famous audio-visual experiments in film history.

The two and half centuries of Mongol rule would have a dramatic effect on Russia. Many historians argue that it was this period of Russia’s history that prevented Russia from developing as a Western state and effectively separated Russia from the West. As well as this, being isolated from Europe meant that Russia missed out on the Renaissance and, according to the political philosopher Pyotr Chaadayev, failed to acquire the universal values of duty, justice and the rule of law. The legacy of the Mongol period is that, rather than developing into a democracy, Russia was transformed into a durable autocracy and civic participation and respect for the law was replaced by judicial torture and cruel despots.

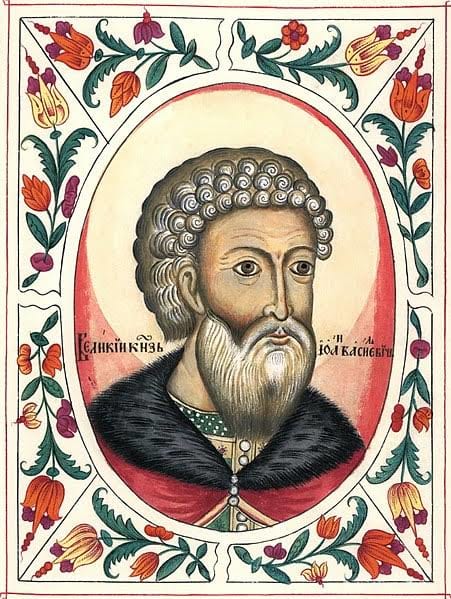

Ivan the Great

Ivan III or Ivan the Great was a Grand Prince of Moscow and Grand Prince of all Rus. He is remembered as tripling the territory of Russia, gaining independence from the Mongols/Tatars and laying the foundations for the Russian state. He served as ruler for 43 years and was the first Russian ruler to style himself as ‘tsar’, although it was not his official title.

Ivan was born at the height of a civil war between supporters of his father, Grand Prince Vasily II of Muscovy (Moscow), and supporters of his rebellious uncles. In 1446, when Ivan was six years old, his father was captured and blinded by his uncle and his sons. Ivan was treacherously handed over to his father’s captors but his father regained power and trained Ivan in the arts of war and government. Ivan was married off to the daughter of the Grand Prince of Yver for political reasons when he was twelve years old and by the time he was 18 he had led successful military campaigns. When his father died in 1462, Ivan became the Grand Prince of Moscow.

Five years later, Ivan’s child bride died (under slightly mysterious circumstances). After her death, Ivan married Zoë Palaeologus, who changed her name to Sophia after the marriage. Sophia was a Byzantine princess and the niece of the Constantine XI, the last Byzantine emperor. The marriage was thought up by Cardinal Bessarion and sponsored by the Pope in the hope of bringing Russia under the sway of the Vatican – a goal that ultimately failed. From Ivan’s point of view, the marriage could help with elevating him as a ruler and later, he took the Byzantine double eagle for his coat of arms.

Ivan’s predecessors had increased Moscow’s territory from less than 600 sq miles to more than 15,000 sq miles and under Ivan, the independent duchies of different Rurikid princes were brought together and single rule was established over them. The princes became noblemen and the former semiautonomous principalities became provinces of Moscow. Ivan spent a lot of his rule engaged in war with Lithuania who had expanded into Russian territory. A peace treaty was eventually signed in 1503 in which Lithuania recognised Russian control over the Polotsk and Smolensk areas.

In 1480, Ivan led a victorious campaign against Khan Ahmed of the Golden Horde that saw Moscow become an independent sovereign and no longer be seen as a vassal of the Khan.

In 1490, Ivan’s eldest son from his first marriage died of gout, leaving Ivan with the predicament of who would be his heir: his eldest grandson, Dmitry, or his eldest son by Sofia, Vasily. In 1497 he nominated Dmitry as his heir, prompting his wife Sophia to plot against her husband. When Ivan discovered her plans to rebel against him, he disgraced both Sophia and Vasily and crowned Dmitry Grand Prince in 1498.

In response, Vasily rebelled again and defected to the Lithuanians. At this time, Moscow was at war with Lithuania and so, in 1502, he gave the title of Grand Prince to Vasily and had Dmitry, along with his mother, imprisoned.

Ivan died in 1505 and it is recognised by historians and academics today that, as a ruler of Muscovy, he did more to lay the foundations of a centralised state and strengthen the authority of the monarch than any other figure. His reign marked the beginning of Muscovite Russia and he established Muscovy as a great power to be reckoned with. His diplomatic and military successes are well documented but despite this, not much is known of Ivan himself, in terms of his personality and virtues.

One thing that Ivan the Great is remembered for is his renovations of the Kremlin. Ivan carried out an ambitious building programme and endowed his city with new cathedrals and palaces. Much of the Kremlin’s current appearance comes from Ivan’s designs. Ivan commissioned a host of Italian architects to bring his vision to life and created the current skyline of golden domes high above red walls.

Ivan the Terrible

The first tsar or czar of Russia (derived from the term Caesar), Ivan the Terrible has an infamous reputation in Russian history, for obvious reasons. However, the original translation of his name, from the Russian word Grozny, is more likely to have meant ‘formidable’ or ‘awe-inspiring’, rather than terrible in the sense that English speakers know it. Although, in his later years it is said he was prone to rages, episodes of paranoia and mental instability. He is credited with transforming Russia from a medieval state into an empire but he also left behind hardly any written records or documentation from his reign.

Ivan the Terrible became Grand Prince when he was just three years older. As a result, a band of advisers or boyars united around him, becoming known as the ‘Chosen Council’. Some say these years being advised, or manipulated in some accounts, by the boyar powers shaped Ivan and would inform his behaviour in later life and his hatred of the boyar class. In 1547, when he was 16, he was declared Tsar of All Rus, establishing the Tsardom of Russia. He was the first person to be coronated with this title and the title established a new unified Russian state. He also married Anastasia Romanovna in a union that tied him to the powerful Romanovna family.

During the first few years of his reign, Ivan is said to have reformed tax collection, introduced self-government in rural areas and instituted statutory law and church reform. The Russia of Ivan the Terrible was surrounded by enemies, with Lithuania and Poland to the west, Sweden to the north and Muslim powers in the south. For this reason, Ivan found a sole ally in England and he communicated frequently, via letters, with the Queen.

Some of his achievements include bringing the first printing press to Russia and establishing the Moscow Print Yard in 1553, as well as overseeing the construction of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. One of the most emblematic symbols of Russia, St. Basil’s Cathedral was commissioned by Ivan the Terrible to commemorate his conquest of Kazan, an Islamic city previously held by the Mongol empire. As well as conquering Khazan, Ivan IV oversaw two other important territorial victories. The first was the defeat of the Crimean horde, bringing southern lands back under Russia’s control. The second was the expansion of Russian territory through expeditions to parts of Siberia that had never been considered part of Russia.

In the 1560, Ivan’s first wife Anastasia died in a suspected poisoning and it is said that her death had a dramatic impact on Ivan, with damaging consequences for his mental health. Ivan fell into a deep depression, becoming increasingly paranoid and behaving more and more erratically. He was convinced that Anastasia had been murdered by the boyars and threatened to abdicate the throne unless he be granted absolute power. He demanded that he should be able to execute traitors without any interference. This is what led to the creation and implementation of the oprichnina, a state policy that involved the mass repression of the boyars, public executions and confiscation of land and property. The oprichnina consisted of a separate territory within the borders of Russia where Ivan exerted exclusive power. Part of the policy also stipulated the creation of the oprichniki, a personal guard whose allegiances lay with Ivan, rather than the government or local bonds. The oprichniki were Russia’s first secret police and they had unlimited powers to crush dissent and recruit informers.

For the next two decades, Ivan conducted a reign of terror, ordering the executions of thousands of people he feared were plotting against him. He alienated many of his former allies and crushed any form of civic society. He grew into a deranged and violent figure. A story that seems to encapsulate the ‘terrible’ side of Ivan is the supposed murder of his son by his hand. As the story goes, in 1581 Ivan beat his pregnant daughter-in-law, Yelena Sheremeteva, for wearing immodest clothing, causing a miscarriage. Upon learning of the beating inflicted upon his wife and unborn child, Ivan’s second son (also called Ivan) confronted his father. The resulting fight ended in Ivan the Terrible striking his son in the head with a pointed staff, killing him. Ivan had been grooming his son for the throne and with his death, the throne was left to his childless son, Feodor Ivanovich.

Ivan the Terrible died in 1584 of an apparent stroke. Under the rule of his unfit son, Russia would spiral into the Time of the Troubles, which would eventually lead to the establishment of the Romanov Dynasty. Ivan the Terrible left behind a complex legacy, having transformed Russia into the expansive state we know today but harming the economy, alienating allies and destroying the boyar class. The country was left with deep political scars after his rule and this was part of the reason the nation was plunged into chaos for almost a century afterwards.

Michael I Romanov

Michael of Russia, also known as Mikhail Romanov, was the first monarch of the Romanov dynasty, who ruled Russia for more than three hundred years. His ascension to the throne saw the end of Russia’s ‘Time of Troubles’ (1584-1613), a period of turmoil characterised by puppet leaders, conmen pretending to be resurrected Tsars and civil war among feuding factions.

Michael was elected as Tsar by a national council known as the Zemsky Sobor (Assembly of the Land). The Zemsky Sobor was a prototype of modern parliament and even some representatives of the peasantry were able to have a say in who was elected as Tsar. It was important that there was broad societal support for the new leader given the decades that the country had spent in civil unrest. Michael was chosen partly because he was the grandnephew of the Ivan the Terrible and thus connected to the Rurik dynasty rulers and thus was seen has having a link to a time when Russia had been militarily strong.

Michael was just 17 when he became Tsar and, in many ways, he was very different from his great-uncle Ivan. Michael was reported to be delicate, sensitive and pious and was often described as giving little trouble to anyone. He relied heavily on the support of the Zemsky Sobor, who met annually throughout his reign, and took on the advice of his counsellors. This had mixed results given that some of his counsellors were honest and capable men and others were corrupt and determined to undermine him.

Under Michael, however, Russia entered a time of prosperity. Michael invited foreign manufacturers to Russia which helped to boost Russia’s diplomatic and trade relations with other countries. Many historians credit Michael with beginning the Europeanisation of Russia by importing Western technologies and improving relations with other European nations. He also reorganised the military, laying the foundations for the creation of the regular national armed forces.

After a brief first marriage (Michael’s first wife died just four months after they wed), Michael married Eudoxia Streshneva, with whom he had ten children. Four of his children reached adulthood and by all accounts the marriage was a happy one. Michael died at age 49 after falling ill in April 1645, leaving the throne to his son Alexis.

Michael, with the help of his government and advisers, restored order in Russia and consolidated her territories, obtaining peace with Sweden and Poland.

Peter the Great

Peter the Great, who ruled the Tsardom of Russia and later the Russian Empire from 1682 to 1725, is recognised as being one of the most influential leaders in Russian history. He is best known for his extensive reforms and establishment of institutions that helped to mould Russia into a great state. His achievements include expanding the Tsardom, facilitating a cultural revolution, secularising schools, creating a strong navy, reorganising the army and administering control over the Orthodox Church. He is generally credited with bringing Russia into the modern age and intensifying the Europeanisation process Michael started.

Peter was the 14th child of Tsar Alexis by his second wife and when his father died, both Peter and his sickly half-brother Ivan V ruled jointly. However, this changed in 1696 with Ivan’s death when Peter was officially declared Sovereign of All Russia. Peter was known for being a giant, both physically and intellectually. Standing at 6 ft 7 in, he is described in various accounts as being well-formed and slim but also a big drinker and reveller. His penchant for debauchery was often frowned upon by members of the aristocracy.

Peter inherited a severely underdeveloped nation characterised by a distrust of the outside world and fierce conservatism. He was determined for Russia to become a great European power and after his brother’s death he travelled to London and Amsterdam, both in search of allies and in order to be able to replicate what he saw as the sophistication of the West in Russia. In 1703 he began the construction of St. Petersburg, which would become the new capital, and it is said that the city was inspired by Peter’s trip to Amsterdam. He also returned from his travels and cut his beard, even going so far as to implementing a beard tax so that citizens would look more European in appearance.

Peter set the foundation for a new Russian culture that was essentially an imitation of Western Europe. He introduced art forms that had previously been forbidden by the church, including portraiture, instrumental music and theatre. By the time of his death, Russians were producing famous ballets, operas and novels. He also modernised the Russian alphabet, introduced the Julian calendar and established the first Russian newspaper. He gained access to the Black Sea and acquired territory in parts of Estonia, Latvia and Finland.

There is no doubt his reign was a turning point in Russian history but while Peter did prove himself to be an effective leader, capable of introducing sweeping changes, he was also known for being cruel and tyrannical. He suppressed revolts and had many of his elite guards tortured and executed when they rebelled against him. He sent his first wife off to live in a convent and ordered his son to be beheaded.

He died in 1725, at age 52, without having nominated an heir.

Catherine the Great

Empress of Russia for more than 30 years, Catherine the Great remains Russia’s longest-ruling female leader. Under her reign, Russia was revitalised and became recognised as a great power of Europe. Her rule is often referred to as the Golden Age of Russia and Catherine presided over the age of Russian Enlightenment. She has been described by historians as an enlightened despot.

Born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, the daughter of a minor Prussian prince, she was summoned to Moscow in 1744 when she was 14 to marry the man who would become Emperor Peter III. Here the church re-christened her Catherine. At the time, Russia was ruled by Peter’s mother, Empress Elizabeth. Catherine and her new husband did not have a happy marriage, although the couple did give birth to one son, Paul. Their rocky marriage meant that both Peter and Catherine began extramarital affairs, sparking gossip that Paul was not actually fathered by the Emperor. None of Catherine’s three additional children would be fathered by Peter and this added to rumours that he was infertile or unable to consummate the marriage.

When Empress Elizabeth died in January 1762, Peter III came to the throne but he was a deeply unpopular ruler. After six months in power, he was overthrown in a bloodless coup organised by Catherine and led by officer Grigory Orlov. Catherine had the support of the people and was proclaimed Empress on 9 July, 1762. Peter III abdicated and was killed eight days later.

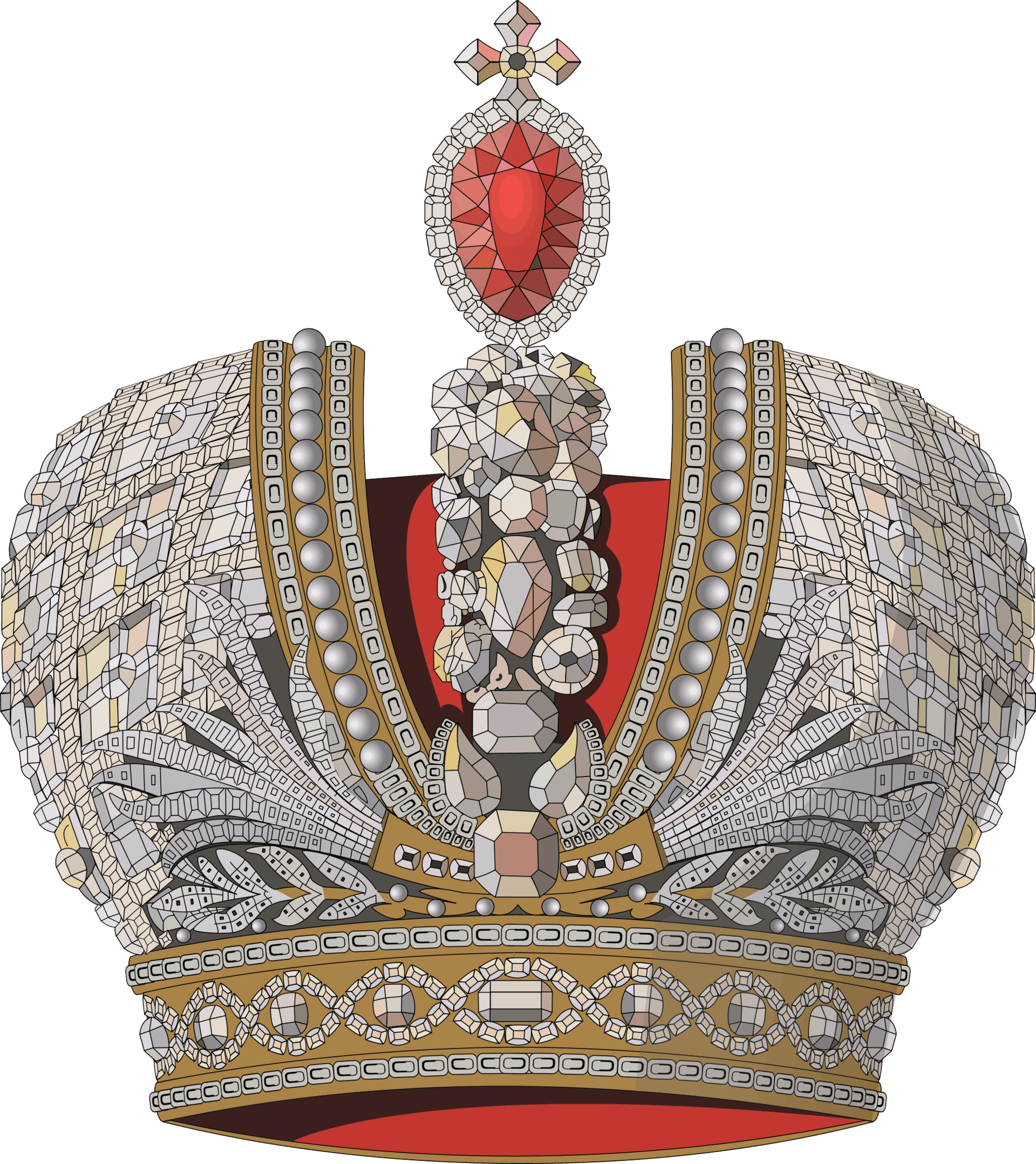

On 22 September, 1762 Catherine was crowned in Moscow with the Imperial Crown of Russia. The crown was designed specifically for the venet by the Swiss-French jeweller Jeremie Pauzie. It is considered to be one of the main treasures of the Romanov dynasty and features two gold and silver half spheres, 75 pearls, 4,936 Indian diamonds and a ruby spinel that belonged to Empress Elizabeth. It is currently displayed at the Moscow Kremlin Armoury Museum.

During her reign, Catherine built on the legacy of Peter the Great by overseeing the expansion of the Russian Empire and further integrating Russia into Europe. She expanded Russia’s borders both southwards and westwards, adding territories which included Crimea, Belarus and Lithuania. The British ambassador to Catherine’s court, George Macartney, describes her leadership:

‘I never saw in my life a person whose port, manner and behaviour answered so strongly to the idea I had formed of her…Russia is no longer to be gazed at as a distant, glimmering star but as a great planet that has obtruded itself into our system, whose place is yet undetermined, but whose motions must powerfully affect those of every other orb’.

Particularly in the early years of her reign, she was seen as ruling with tact and dignity, a progressive reformer who was determined to Westernise the country. She was fiercely intelligent and a keen reader, who enjoyed corresponding with Voltaire and studying philosophy. In 1767, she convened an All-Russian Legislative Commission and presented them with her Nakaz (‘Instruction’) to create a new code of law. The document was strikingly liberal in its approach, professing the equality of all men and rejecting capital punishment and torture. The outbreak of war against the Ottoman Empire the following year prevented its implementation but it is often cited as evidence of Catherine’s desire for a stronger civil society.

While she began her reign as a political and social reformer, Catherine grew more conservative with age. She realised that she needed to exercise more control over the people and began to restrict the rights of serfs, despite once having labelled the system of serfdom as inhumane.

In popular culture, Catherine the Great is notorious for her many lovers, whom she often elevated to high positions and gave large estates. While rumours abound about the aristocrats and military men she supposedly had relationships with, it was Grigory Potemkin who was considered to be the love of her life. Correspondence between the pair shows their affection for one another (Catherine wrote Potemkin a letter in which she said ‘My heart cannot be content for even an hour without love’) and scholars say the affair could be described as an open relationship with the couple staying in contact until Potemkin’s death.

Catherine the Great died of a stroke on Nov. 17, 1796. Prior to her death she had been attempting to install her favourite grandson Alexander as heir to the throne, superseding her difficult son Paul, but she died before the announcement could be made.

The story of the remarkable Catherine the Great concludes our journey through early Russian history, tracing the story of the Russian state from the mythological Rurik dynasty to the country’s most famous female leader. In the future articles in this series we will look at the decline of the Romanov dynasty, the rise of revolution and the dictatorship that followed. Examining the roles the leaders mentioned above have played has given a sense of how the character and identity of Russia was formed and its complicated relationship with Western Europe and its neighbouring countries.

If this article has sparked your interest in a small group tour to Russia, please take a look at the tours on offer with Odyssey Traveller. Our tours visit heritage sites and key attractions as well as hidden gems and lesser-known spots, making for a unique and incredible travel experience. You will see firsthand the history discussed in this article including discovering more about Russian tsars, Russian folklore, the Iron Curtain and the days of the Soviet Union. Each tour allows you to discover colourful and beautiful Russian cities and understand the complexity of this beautiful and mighty country.

Related Tours

days

JulJourney through Mongolia and Russia small group tour

Visiting Mongolia, Russia

This escorted small group tour traverses this expanse, from Ulaanbaatar to St Petersburg; from the Mongolian Steppes to Siberian taiga and tundra; over the Ural Mountains that divide Asia and Europe to the waterways of Golden Ring. Our program for couples and solo travellers uses two of the great rail journeys of the world; the Trans Mongolian Express and the Trans Siberian Express.

From A$17,850 AUD

View Tour

days

Oct, MayHelsinki to Irkutsk on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Finland, Russia

Escorted tour on the Trans-Siberian railway network from West to East starting in Helsinki and finishing in Irkutsk after 21 days. This is small group travel with like minded people and itineraries that maximise the travel experience of the 6 key destinations explored en-route. Our small group journeys are for mature couples and solo travellers.

days

Apr, AugIrkutsk to Helsinki on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Finland, Russia

Escorted tour on the Trans-Siberian railway network from East to West starting in Irkutsk and finishing in Helsinki after 21 days. This is small group travel with like minded people and itineraries that maximise the travel experience of the 6 key destinations explored en-route. Our small group journeys are for mature couples and solo travellers.

days

Apr, AugVladivostok to Krasnoyarsk on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Russia

Mature and solo travelers group Travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway for 22 days covering the second half of the Trans-Siberian journey, from Vladivostok to Krasnoyarsk in the heart of Siberian Russia Small group journeys with a tour leader, explores 5 key cities with local guides providing authentic experiences in each with stops of 2-3 nights.

22 days

OctKrasnoyarsk to Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian Railway

Visiting Russia

Mature and solo travelers group Travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway for 22 days covering the second half of the Trans-Siberian journey, from Vladivostok to Krasnoyarsk to Vladivostok on the edge of Siberian Russia Small group journeys with a tour leader, explores 5 key cities with local guides providing authentic experiences in each with stops of 2-3 nights.

From A$12,650 AUD

View Tour