Egyptian Linen Treasures

Egyptian linen treasures Egypt has long held a place in the imagination of curious travellers. Many of us were introduced to the stories of pyramids, pharaohs and buried treasure as children, and since then, books…

22 Jan 19 · 8 mins read

Egyptian linen treasures

Egypt has long held a place in the imagination of curious travellers. Many of us were introduced to the stories of pyramids, pharaohs and buried treasure as children, and since then, books and films have created ancient worlds we briefly inhabit, before returning to our modern lives. The fascination with Egypt itself has a long history. The promise of undiscovered tombs proved irresistible for those adventurers who devoted themselves to the field of archaeology. And Egyptology, though compelling, was challenging and often slow. On the 4th of November, 1922, the forty-eight-year-old English archaeologist Howard Carter would despatch an urgent telegram to his long-suffering patron Lord Carnarvon. This was finally it: he had uncovered a passage leading to a royal tomb.

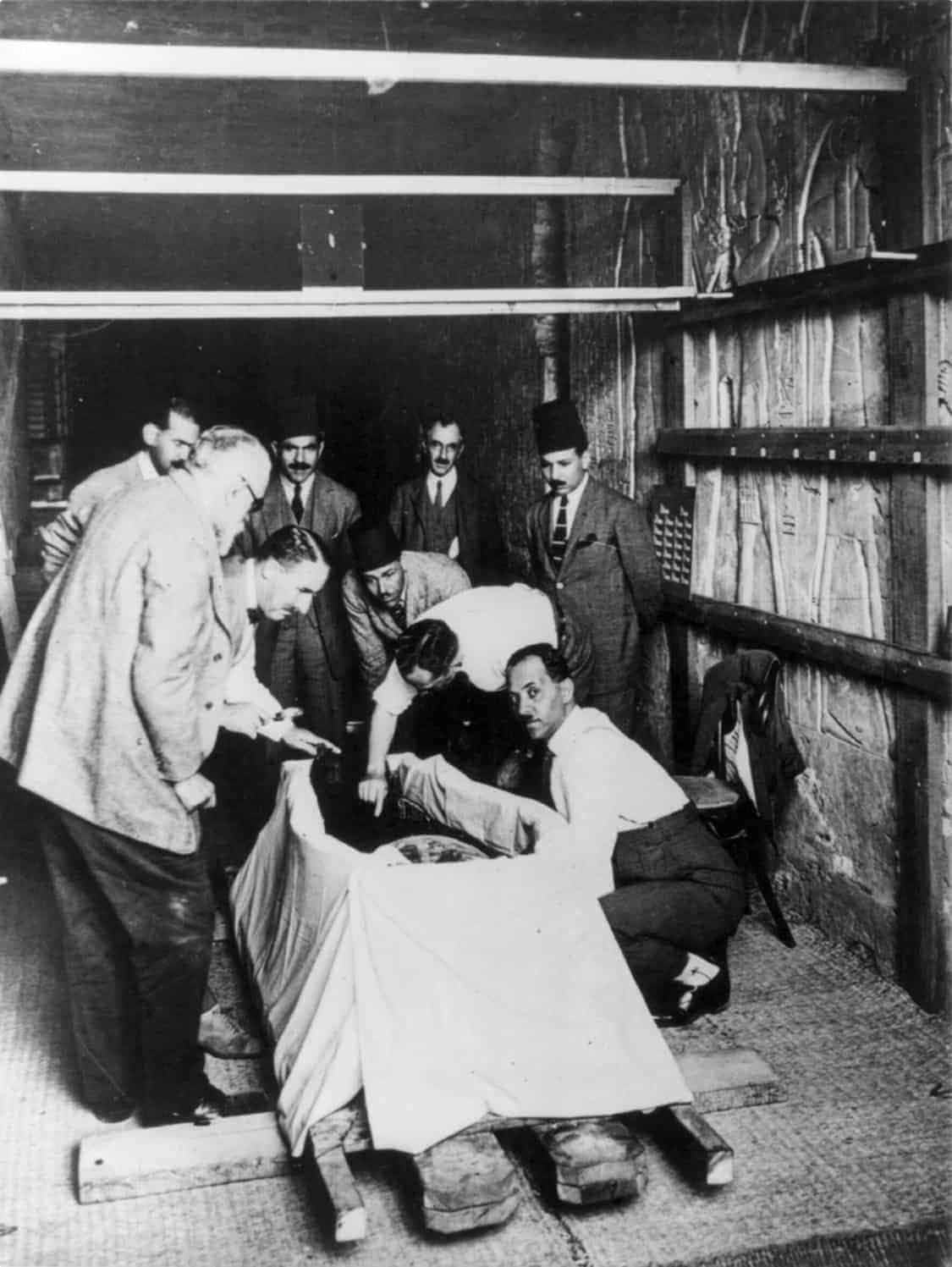

Tutankhamen’s tomb

Three weeks later, Carnarvon stood beside him as the pair peeked into the darkness, guided by candlelight. This was the tomb of Tutankhamen, and after three further, painstaking years of careful excavation (archaeologists would decry the damage left by looters who worked in haste), Carter finally laid his hands upon the linen wrapping the mummy of the young king. Carter dutifully recorded that “The outer wrappings consisted of one large linen sheet, held in position by three longitudinal (one down the centre and one at each side) and four transverse bands of the same material” (Carter & Mace, The Tomb of Tutankhamen, 107). As Kassia St Clair reports, however, this cloth was deemed “a lacklustre side dish” (The Golden Thread, 38); Carter would go on to hack through these layers to reach hidden treasures and, of course, the mummy itself. In doing so, he missed the significance of linen to the burial technique. He also overlooked a source for further understanding how the ancient Egyptians lived. Read on to discover more about linen in Egypt – part of our article series on the world history of cloth.

Egyptians produced linen using intricate techniques

We are fortunate that examples of textiles from Ancient Egypt remain relatively intact. From samples now housed in museums, along with relics of spindles and whorls, paintings and miniatures, we know that the flax plant was used to cultivate linen. This blue-flowered crop thrived in the city of Sais by the Nile and Mediterranean delta, favouring humidity. It is believed seeds were sown in close proximity to encourage height and longer fibres. The process of its cultivation is complex. The flax stems would have been dried, then shaken or combed to remove the seed heads. The inner bast fibres would be exposed, followed by further drying and the delicate removal of all traces of bark and woody matter. Miraculously, the methods used by the Egyptians separated the basts as thoroughly as modern machinery (St Clair, 41).

Weaving the linen on heavy looms

In 1920, twenty-four wooden statues were among artefacts discovered in the tomb of high steward Meketre (buried between 1981 and 1975 BC). These figural statues depict the processes of making what Meketre might need in the afterlife, including bread, beer and linen. From these models, we can glean that women would twist roves of flax fibre between their thighs and hands. And that the newly formed thread was wound into balls then spun with spindles. The thread was weaved using horizontal, and later vertical, looms; cumbersome instruments operated by two women at once. The result was linen of quality and robustness, worn by Egyptians in simple designs draped against their bodies. This is supported by imagery in surviving wall paintings, along with artefacts stored in tombs. Sometimes richly coloured, most linen was dyed a creamy white, believed to be a reflection of cleanliness and purity. It adorned both the living and dead.

Linen was used to wrap statues and other objects too

Carter discovered that it was not only Tutankhamen shrouded in a total of sixteen layers of linen in the depths of his tomb. Statues and other objects had been similarly treated, wrapped in fabrics that ostensibly protected them from the elements. However, this was the first live discovery of a practice already understood from surviving rites and paintings. Statues were not simply “wrapped” for safe keeping but stored in shrines where they were dressed at least daily, in private, by priests. Christina Riggs argues in Unwrapping Ancient Egypt that the ritual itself strengthened and renewed the statues’ meaning. Linen, it seemed, conferred great significance upon whatever it happened to enrobe.

Intricate wrappings

Linen was an important part of life in ancient Egypt. It was also an important part of death. This is no clearer than in the mummy of Senebtisi. This slender woman was aged around fifty and estimated to have died in 1800 BC. She was discovered in a tomb in a pyramid at Lisht, encased within a series of nested coffins like a Russian doll. The innermost coffin was draped in linen shawls. Her body was also carefully wrapped in linen; originally supine, she had slipped to her side as the coffin had shifted. Each limb had been wrapped separately, and her arms arranged straight down with her hands in her lap. Her entire form was encased in alternating bandages and sheets of linen. They were badly decayed, but the innermost wrapping was of exceptional quality with around fifty by thirty threads per centimetre.

Sculpted linen

Over time, the mummification process had evolved to include the removal of internal organs. This is because they sped up the process of decay. In the case of Senebtisi, the internal cavity was also stuffed with linen. Scientists were amazed to discover that her heart had been stoppered with wads of linen and carefully replaced into her body.

While Tutankhamen was wrapped in sixteen distinct layers of linen, the mummy Artemidona was wrapped in so much linen that her length was extended by a full third. Her feet were wrapped in such a fashion that her shape resembled a supine ‘L’, reaching almost a metre into the air. St Clair uses the word “sculpted” to describe these mummies; the stiffened layers of linen seeming to pose these venerated bodies within their coffins.

Masters of secrets

The wrapping itself was an elaborate and ritualised process, conducted within a special room floored with sand and topped in papyrus mat and linen. Attendants would shave, wash, and dress in fresh linen: a purification process before they could begin. Priests would perform the physical bandaging and favoured layers in multiples of three and four. These priests were given the name of “masters of secrets” – a reflection of the great respect given to this role. You can find out more about the mummification process here. The wrapping process alone would have taken up to weeks. Old texts reveal a rich vocabulary used by Egyptians to detail these processes and dressings. There were at least three different verbs for the application of textiles to a body: wety for wrap, djem or tjam for covering, and tjestjes meant to fasten with knots. Sah was a word for a wrapped figure wearing a divine head covering, like Tutankhamen in the gold mask Carter prised from his face.

The “spoils” of science

Tombs were looted for their buried treasure, often leaving a trail of destruction to be rediscovered by archaeologists later on. Fortunately for these dedicated researchers, the mummies themselves often remained. As modern science developed, mummies were prized as sources of rich discovery. In 1825, Augustus Bozzi Granville presented research to the Royal Society on “his” mummy. Purchased years prior for a fee of four dollars, “Granville’s mummy”, as it is known, is believed to have been the first modern autopsy of mummified human remains. St Clair describes his scrupulous attention to detail; the recording of 28 pounds of cloth he laboriously unwound from the body. The autopsy took six weeks, during which he took note of her large breasts and wrinkled stomach and the stubble of hair on her shaved skull: too-intimate details that betray his fascination with this incredible resource. His estimations proved wrong, in time: she was not the victim of an ovarian cyst but likely tuberculosis or malaria. But Granville’s treatment of his mummy reveals how the bodies themselves were effectively pillaged for treasure.

Ancient treasures

St Clair compares history’s archaeologists with the looters that plundered tombs of gold and jewels. As Carter and his team employed ever more violent means to reach the amulets and jewellery clothed in linen against Tutankhamen’s remains, the body itself was left “not in one piece”. St Clair recounts one researcher’s testimony that “The head and neck were separated from the remainder of the body, and the limbs had been detached from the torso… Further investigation showed that the limbs were broken in many places” (cited in St Clair, 54). The linen torn from his body, Tutankhamen was replaced in his tomb sans the sculpted form perfected 3,360 years prior. As St Clair argues,

“Our preoccupation with the bodies and treasures hidden within the linen… fails to capture the value and significance of the linen itself… Wrapping did help to preserve bodies, but this doesn’t seem to have been its primary purpose. The special, mummiform shape of the sah, with its headdress and mask, was associated in Egyptian art with the divine. Humans were sculpted, using linen, into this form in order to be imbued with divinity. As a body was embalmed and enfolded, it was being transfigured into something worthy of veneration” (53).

Linen was valued by Egyptians: they stored flax as currency, they wore its soft cloth against their bodies in the oppressive heat, and they used it to wrap or “sculpt” items and beloved people to be cared for in the afterlife. Linen wasn’t protecting treasure, it was treasure – and it is one that lives on in modern society, scarcely even attracting our notice.

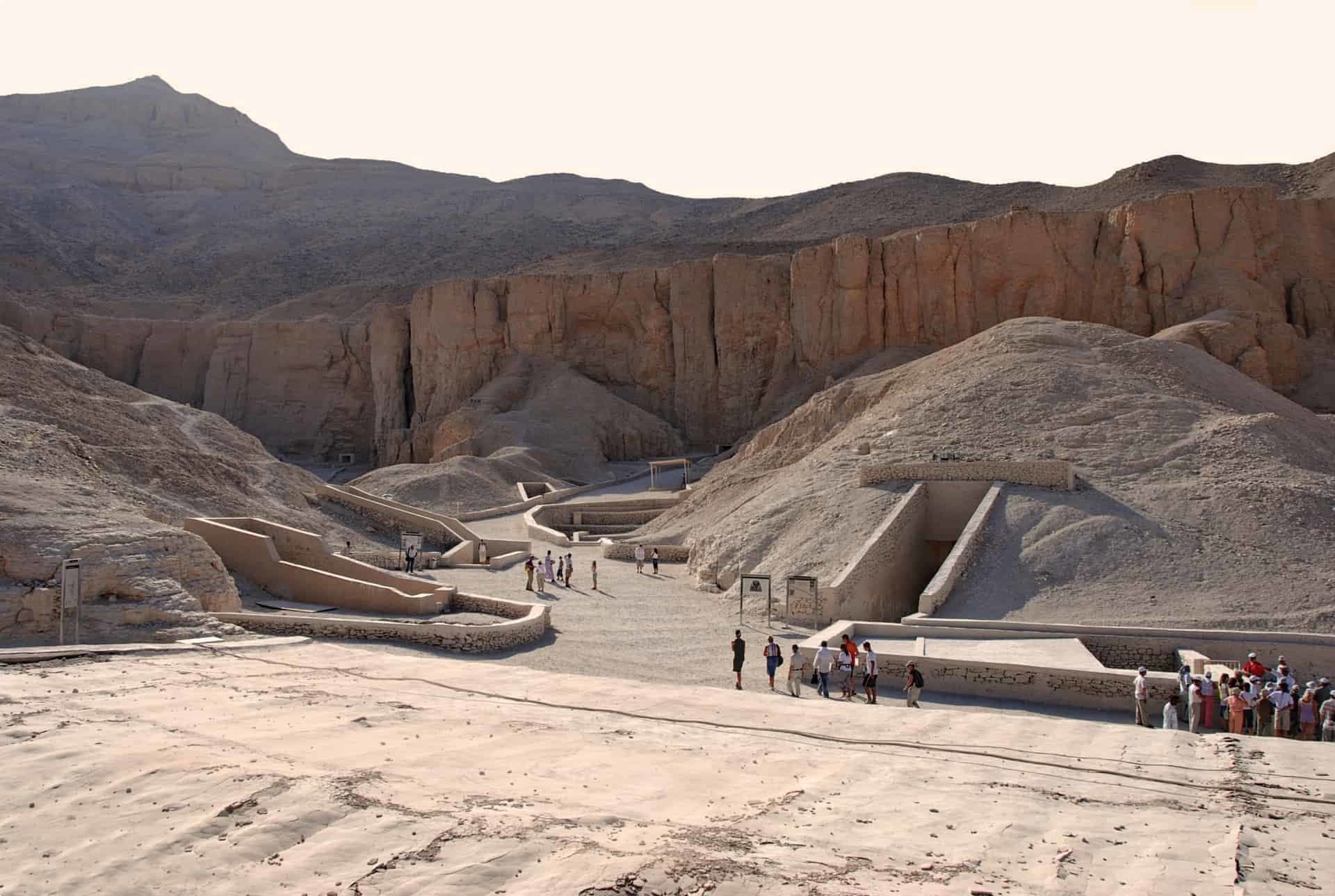

Travelling in Egypt

Egypt is the ultimate bucket list destination for many world travellers. Few experiences can rival standing before the ancient pyramids, and modern Egypt and its culture is equally fascinating. The best way to experience Egypt it on a small group tour. On Odyssey Traveller’s small group tour of Egypt, you are accompanied by a team leader, meet with local guides, and even a specialist Egyptologist. Odyssey tours are specifically designed for seniors with a passion for learning. This article is part of a series on the history of fabric – an interesting and underappreciated source for understanding how people lived. You might like to read about how clothes began in Georgia; or the history and legacy of the Silk Road, where trade routes defined cultures. You can learn about the history of Persian carpets: centuries-old art forms. We also examine the history of women’s fashion in the Victorian era – a period we focus upon in our tour of Queen Victoria’s England.

Kassia St Clair’s excellent 2018 book How Fabric Changed History informs our article here, and we recommend it for further reading on a unique take on world history.

About Odyssey Traveller

Odyssey Traveller is famous for our small groups, and we average eight participants per tour. Our maximum group size is eighteen people, which ensures quality, flexibility and care that is tailored to our clients. We specialise in small group tours for the senior traveller who is seeking adventure or is curious about the world we live in. Typically, our clients begin travelling with us from their mid 50’s onward. But be prepared to meet fellow travellers in their 80s and beyond! Both couples and solo travellers are very welcome on our tours.

Odyssey Traveller is committed to charitable activities that support the environment and cultural development of Australian and New Zealand communities. Accordingly, we are pleased to announce that since 2012, Odyssey has been awarding $10,000 Equity & Merit Cash Scholarships each year. We award scholarships on the basis of academic performance and demonstrated financial need. We award at least one scholarship per year. We’re supported through our educational travel programs, and your participation helps Odyssey achieve its goals.

For more information on Odyssey Traveller and our educational small group tours, visit our website. Alternatively, please call or send an email. We’d love to hear from you!

References

Carter, Howard, and Mace, Arthur C., The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen: Discovered by the Late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter, vol II (London: Cassell & Co., 1923).

Riggs, Christina, Unwrapping Ancient Egypt (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014).

St Clair, Kassia, The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History (London: John Murray, 2018).

Related Tours

18 days

Nov, JanEgypt tour: escorted small group history & cultural tour of Egypt

Visiting Egypt

Our small-group program, designed for senior couples and solo travellers, offers a rich journey through Egypt's past and present. You'll explore modern marvels like the Aswan Dam and immerse yourself in pivotal sites such as Tahrir Square, both key to understanding Egypt’s enduring influence on civilization. This tour is proof that Egypt remains a vital crossroads of history and culture. We explore Egypt's fairy-tale natural beauty, its ancient history, and Imperial heritage, its World Heritage Sites, and world famous cities, all with some truly spectacular scenery along the way. For those seeking an even deeper experience, we also offer opportunities to extend your travels with our tours in Morocco, Jordan, or Tunisia before beginning your Egyptian adventure.

From A$13,450 AUD

View Tour

14 days

Apr, Sep, MarTour of Tunisia

Visiting Tunisia

Join Odyssey Traveller on this small group tour of Tunisia in North Africa for couples and solo travellers, where Carthaginian ruins sit side by side with Roman monuments, grand Islamic mosques, Arabic souks and medina, and honeycomb-like Berber cave dwellings and hilltop villages.

From A$11,650 AUD

View Tour

20 days

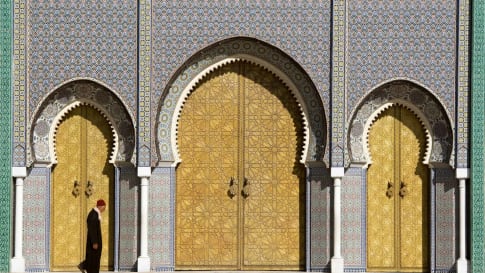

Apr, Oct, MarMorocco tour for senior travellers

Visiting Morocco

Embark on an unforgettable journey through Morocco: A Gateway to a world of vibrant colors, cultural diversity, and endless wonder. Join our escorted small group tour designed for senior travellers, whether you're a couple or a solo adventurer, and immerse yourself in the captivating allure of Casablanca, Fez, Meknes, Rabat, Marrakech and beyond. Experience the richness of Moroccan traditions and heritage as we explore this enchanting destination.

From A$12,750 AUD

View Tour