West African Gold and Empires

The surging gold trade in West Africa transformed cities like Gao and Timbuktu into vibrant hubs of trans-Saharan commerce. This article explores the importance of this trade and early globalisation. An Antipodean travel company serving World Travellers since 1983 with small group educational tours for senior couples and mature solo travellers.

17 Jul 24 · 18 mins read

Gold and Empires of the Sahel

European expansion is often seen as the trigger for modern history, but in reality, globalisation came even earlier to West Africa’s Sahel region, underpinned by the gold trade. Analysis by archaeologists of the gold coins used in Tunis and Libya suggests a major change around the ninth century CE, when gold from the forest regions of what are now Ghana and Ivory Coast was dug out in large quantities and exported through networks of local traders. Then, for several centuries from around 1000, the gold of Christian Europe and the Muslim world came largely from West Africa, and it was the growth in production there that produced the ready-cash economy.

The surging gold trade in West Africa transformed cities like Gao and Timbuktu into vibrant hubs of trans-Saharan commerce, enriched local economies, led to the consolidation of important states such as Kano in northern Nigeria and Mossi in Burkina Faso, and drove the rise of powerful empires like Mali and Songhai.

Religion also played a pivotal role, uniting communities and fostering stable political entities. Islam spread through trade connections, coexisting with persisting local beliefs and traditions. These dynamics not only shaped cultural identities but also propelled West Africa onto the global stage, exemplified a legendary pilgrimage of Mali’s Mansa Musa, which showcased the empire’s wealth and influence.

However, West Africa’s engagement with the broader world also brought challenges. External pressures, such as Portuguese and Moroccan incursions, reshaped regional dynamics and contributed to the eventual decline of indigenous empires. Despite these challenges, the legacy of West Africa’s medieval city-states and empires endures, reflecting a history of resilience, cultural exchange, and enduring spiritual traditions that continue to shape the region’s identity to this day.

This article explores the complex interplay of religion, gold, and political ambition in West Africa’s Sahel. It is intended as background reading for Odyssey Traveller’s 21-day West Africa Tour: Ghana, Togo, and Benin. Much of the information is sourced from Toby Green’s A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution.

Continues Below.

Religion, Gold, and City States of the Sahel

Religion was crucial in shaping West African political structures in this period. Recent archaeological work in Mali has demonstrated that the creation of collective shrines helped to unite villages into broader political entities, with shared worship fostering common political identities. By uniting various villages under sacred protection, both collective security and a collective identity could be ensured.

Similarly, religious practice associated with gold production could be shared across larger communities in the forest areas between the Sahel and the Atlantic Ocean. Religious powers were hugely important in gold production, as miners sought protection from malevolent spirits and occult powers. The belief that such protection is required for gold miners in West Africa remains widespread to this day. As the power of the gold trade grew, so did the power and respect of those involved in gold mining, along with their religious practices.

Although growing in popularity at the time, Islam could not yet supplant the power of the smiths, who were long associated with strong occult powers in many West African societies. However, as trade across the Sahara Desert intensified, differences in religious practice between rulers and those who worked in their kingdoms grew.

Islam found favour among elites due to the wealth brought by Muslim traders, known as the Wangara, to West African city-states. Diasporas of traders linked by shared identities were vital for connecting the extended geographies that underpinned trade: the forest zones from which the gold was mined, the savannah where the city states grew, and the desert that had to be crossed if the whole system was going to work. Only communities of traders united by shared beliefs could bridge these vast geographical divides and navigate perilous trading networks, making Islam increasingly important in this context.

Thus, with the expansion of the gold trade, different approaches to religion became necessary. On one hand, Islam provided access to a broader world, and literacy in Arabic helped build bureaucracies for rulers. On the other hand, gold miners jealously guarded their own beliefs and resisted adopting Islam as a way to protect their privileged access to the mines.

This dynamic was evident in the city state of Gao. Located at the northernmost point of the Niger, Gao was always an influential centre, with access both to the Sahara and to the rest of the region. Commercial trade from Gao to North Africa had increased from the seventh century onwards, and cotton was grown to trade across the Sahara by 1300. By 1000, Gao had already established strong trading links with the Islamic kingdoms of southern Spain, evidenced by marble funeral stelae made in Almería and Andalusian glazed ceramics found in the city.. Despite this, formal Islam did not spread far beyond the elite.

A key state in the emergence of Islam in West Africa was much further east, in Kanem-Borno, in north-eastern Nigeria. In this region, where scrubland transitions into deserts, ancient accounts of the Borno mais (kings) date back to the eleventh century, when they originally founded Kanem, north of the present Nigerian state of Borno.

By the end of the century, Islam had been consolidated amongst the ruling class in Kanem-Borno, with Mai Umme’s decision to convert grounded in the influence Arabic learning and instruction had in shaping centralized kingdoms in the Sahel from c. 1000 CE, and of the place of trade from West Africa in securing this learning. Politically, the priority was building a bureaucratic state, and what mattered economically were the exchanges of value through a trade in currencies (gold and silver), carried by caravans north across the Sahara to Algiers, Cairo, Tripoli and Tunis, alongside the trade in captives, which was already important.

The kings of thirteenth- and fourteenth- century West Africa relied heavily on this trade. Just as Gao urbanized by the end of the twelfth century, so the Kano Chronicle tells us that Kano’s walls were completed by the end of the reign of the fifth sarki, Yusa (c. 1136– 94). Increased trade led to more wealth and resources, which were crucial for defending this material power. However, it also led to conflict and divide between the gathering power of Islam and existing African religious practice. In time, however, the two frameworks would mesh, with religious and political power remaining interwoven down the centuries.

Globalizing Empires

The thirteenth and fourteenth centuries saw significant political transformations in the Sahel. Independent of any European influence, these changes were internally driven and directed. State institutions and power expanded through international connections, and standing armies protected the political authority of the rulers and their aristocracies.

According to Green, four key underpinned the increasing complexity of these political systems and structures: the diverse composition of communities; the globalization of movement; the expansion of the labour force; and the region’s role in global trade through the place of currency use.

The first key factor involved accommodating indigenous African religiosity alongside Islam. By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the elites had widely adopted a form of Islam influenced by tolerant currents of Islamic philosophy. This strain of Islam emphasised learning and pacifism, which was vital in a region where practitioners of African religions still outnumbered Muslims. The creation of a mixed and plural society was to become a hallmark of West African life.

In the emerging superpowers – Kano, Borno, Mali and then Songhai – historically grounded African religious customs practices therefore remained widespread, melded with the new religion. Kings needed to communicate to both their Muslim and non- Muslim subjects, and this required a flexible approach. Elites developed states founded on indigenous practice, with a warrior cavalry aristocracy, and using the traditional hunters’ and blacksmiths’ societies and manufactures as symbols of their kingship. However, they also incorporated Islamic bureaucratic forms, religion, scholarship and legal structures to govern the new state.

The second factor, growing globalism, meanwhile, was seen in the large numbers of pilgrimages from West Africa to Mecca via Cairo and other North African cities, as well as in the exchange of scholars. In return, many craftsmen and scholars from North Africa and Andalusia travelled to Mali, using the trade routes along which caravans transported gold and enslaved persons.

Regarding the third factor, expanding the labour force, slaving had grown significantly in West Africa by the fifteenth century. As in many other parts of the world, it relied on the capture of ‘outsiders’ in war. The growth of the external slave trade in Borno, Kano, Mali and Songhai also saw the growth of relations of dependence within West Africa itself. These relationships often provoked disputes, fundamentally driven by the growing financial value assigned to enslaved persons. Indeed, money, slavery and political power were intertwined in the West African kingdoms of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The fourth factor concerned the use of currency in the region’s global trade. In Borno, for example, multiple currencies operated. The standard currency was a piece of cloth measuring 10 cubits in length, and that was used to make purchases from ¼ cubit upwards. Cowries, copper, coined silver and beads were also used as currency, but they were all valued in terms of that cloth.

Money as a representation of value was becoming increasingly powerful. By the end of the fifteenth century in Songhai, traders often adulterated gold and silver with copper dust, or did not fully separate sand from gold dust. By the fifteenth century, ‘hard’ currencies, such as cloth in Borno, and gold in Mali and Songhai, were increasingly capturing a kind of pretended ‘universal’ value in the trade, becoming central to commercial exchanges.

Mali Empire

Having begun to grow in the 11th and 12th centuries, by the middle of the fourteenth century, Mali was the largest empire in West Africa, with growing global connections. Under the rule of Mansa Musa, who reigned from 1312 to 1337, the empire expanded significantly, reaching its peak in terms of territorial extent, wealth, and influence. Mansa Musa’s famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324-1326, notable for the large amounts of gold he left in Cairo along the way, showcased the empire’s immense wealth and solidified its status as a major power.

The Mali Empire during this period encompassed a vast area, including parts of modern-day Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, and Mauritania. Its influence extended over crucial trans-Saharan trade routes, which facilitated the exchange of gold, salt, and other goods, further enhancing its economic and political dominance in the region.

By this point, the grandeur of the Court of the Emperor of Mali was becoming well known in the Mediterranean worlds. Contemporary writers in the reign of Mansa Musa described his court as adorned with three arches decked out in sheets in silver, beneath which were adorned in gold. When the emperor held an audience, 300 slaves would emerge from the palace gates with bows, lances and shields. Additionally, each provincial governors were preceded by their own followers with lances, bows, drums and trumpets. This military might of the empire included an army of 100,000, including 10,000 cavalry.

Islam had assumed a pivotal role in the Mali Empire. Passing through Songhai on the return journey of his pilgrimage, Mansa Musa had a mosque built at Gao. Then, upon reaching Timbuktu, he ordered the construction of the palace there and the Djinguereber Mosque. Designed with input from the Andalusian architect Al-Sahili, who was born around 1290 in Granada, the Djinguereber Mosque was built in an urban centre that combined North African and Islamic Iberian architectural styles, while also integrating indigenous West African cultural elements throughout.

As Mali’s power expanded, the empire depended heavily on its control of the Niger River. The Joliba (as it was known in Manding) was the vital artery for the transport of foodstuffs to the communities nearby, and for trading networks to develop once products had crossed the Sahara.

Meanwhile, the size of the caravans bringing these goods grew tremendously large. Some accounts suggest that caravans linking Egypt and Mali included as many as 12,000 camels – an almost unbelievable number. With these global connections came the establishment of more complex state mechanisms to regulate travel and trade, to secure taxes for the running of the administration, and to uphold Mali’s regional dominance.

Mali was becoming bigger, stronger and richer in the fourteenth century. It had conquered neighbouring territories, and its power extended to the Atlantic. Preserving such wealth, however, also required the development of a state sponsored apparatus of persecution. Each commander controlled a contingent of officers and troops, leading to tendencies of tyranny, high- handedness, and the violation of people’s rights in the latter days of their rule. Mali’s power was nothing if not hierarchical, and these deep inequalities fostered internal divisions.

Beyond areas of formal political control, Mali’s cultural influence also grew. The royal manifestation of power was certainly acute in Borno, but nevertheless there was a strong cultural influence from Mali. By the fifteenth century, an increasing number of Wangara traders in the kingdom were accompanied by numerous scholars and preachers who brought books and new ideas.. This did not lead to formal political control, however, and Borno remained a powerful kingdom, with Kano being subordinate to it long into the fifteenth century.

Thriving Gold Trade

Gold and the exchange of value through currency had come to have a symbolic importance by the fourteenth century. The role of gold in Mali’s power was notably evident in Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage, which historians often highlight as the pinnacle of this association.

However, the gold trade did not become static after the 1320s. In fact, it expanded. By the fifteenth century, the major source of Akan gold production in the Volta River Basin was connected to Borno. Traders from Borno exchanged locally produced cloth for gold in this region, which they then transported northward to Tripoli.

So extensive was the gold trade in the forests of the Volta River at this time that, within twenty years of the Portuguese arrival on the Gold Coast in the 1480s, it was able to supply 30,000 ounces annually. Impressive technologies were developed to enhance production, enabling gold to be mines to depths of nearly 230 feet.

In fact, there was an overproduction of gold, which could not be sold for the volume of goods that the trans-Saharan trade was able to provide. This situation had profound effects in West Africa, contributing to terms of trade that were unequal. The cost of even the most basic manufactured goods in Gao was significantly higher than what would be paid in Europe.

The overproduction of gold by West African miners and traders on the one hand, led to profiteering on European trade goods on the other. Initially, these profits were largely captured by middlemen in the trans-Saharan trade. However, as trade dynamics shifted from the desert to the ocean, these profits and the subsequent capital accumulation increasingly fell into the hands of European traders.

Political Transformations

The thriving gold trade was a key driver of profound political transformations during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The expansion of gold production meant that there were new trade routes. The Borno traders who went to buy gold in the forests of the Volta brought cloth, so cloth manufacturing grew in Borno. This increased demand for traders, expanding the foreign-trader communities in West African city-states and thereby the influence of Islam in the region.

Meanwhile, the burgeoning trade necessitated new governmental structures to manage its complexities. In Borno, this prompted the relocation of the capital from the old centre of Kanemould lead to further south to Ngazargamu around 1470. Additionally, in Kano, the establishment of the Sarauta system introduced a new administrative framework to effectively govern and regulate the evolving trade dynamics.

However, what is even more remarkable than these changes within an existing kingdom like Borno is the broader political transformations that took place across West Africa, spanning from Senegambia to Nigeria. The expanding gold trade not only supplied a significant amount of currency for the North African and European market, but also supered the growth of trading routes and the development of governmental systems to regulate them.

This led to the he emergence of new states, the transformation of existing ones, and significant migrations of peoples. Armies expanded, and communities fortified themselves by constructing new defences or relocating to more defensible locations.

For example, the Mossi Kingdom rose in the fifteenth century in what is now Burkina Faso, fuelled by the revenue generated from taxing the gold passing through the Volta forests. Around the same time Bono-Mansu, an Akan state located closer to the goldfields on the Gold Coast, also rose to prominence. Meanwhile, the key gold- trading centre of Bighu, also situated on the Gold Coast, began to gain importance during these decades, a trend that would continue especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In other regions similar transformations were afoot. In Mali, the famous Dogon people of the Bandiagara escarpment probably moved there in the fifteenth century. The steep nature of the cliffs made this a much easier area to defend against attacks. Fourteen different languages are still spoken among the Dogon, making it clear that this was not one ‘ethnic’ population movement, but rather a common gathering of people seeking sanctuary from increasing militarization and insecurity.

Many of these peoples had probably had connections to the trans-Saharan trade, since some of the textiles found here from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries reveal Islamic- influenced designs. They also appear to have had a sophisticated astronomical system, according to some researchers.

Near to Bandiagara, the city of Djenné was famous as a major marketplace for the exchange of gold and salt. Meanwhile, in Senegambia, the rise of the military leader Koli Tenguella at the end of the fifteenth century probably coincided with an attempt to control the gold trade that came from the Kingdom of Wuuli, on the north bank of the Gambia River. Tenguella, of the Fula people, would eventually lead an army south across the Gambia to the Fuuta Jaalo Mountains in what is now Guinea-Conakry and establish communities there, before returning to establish the Kingdom of Fuuta Tòòro.

Thus, West African mining technology, economic transformation and political reorganization facilitated the framework in which European powers sought to expand their knowledge of the world, as they began to sail along the West African coast in the fifteenth century.

The dynamics of these developments are evident in Borno. After the Ottoman Empire’s conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the sultans in Istanbul became significantly involved in the affairs of the Borno Kingdom. This involvement was such that later rulers of Borno were able to count them as allies. In the fourteenth century, Borno had established strong diplomatic ties with the Mamluk sultans of Egypt and to the kings of Abysinnia (Ethiopia). Borno’s pivotal role as a hub for the gold trade made leaders like the Ottoman sultans eager to ally with its rulers, underscoring the trade’s critical role in bolstering their own authority from the outset.

Kano

The most notable example of political transformations in the fifteenth century occurred in northern Nigeria. While the trans-Saharan trade was crucial, even more significant was the regular regional trade in food, raw materials, animals, and manufactured goods, particularly cloth. Kano experienced rapid growth in the fifteenth century, launching military expeditions to the south and emerging as a regional hub connecting trading networks from southern Nigeria to present-day Mali and beyond.

By the 1450s, Kano’s commercial expansion attracted merchants from Gonja (in modern northern Ghana), along with many Hausa diaspora traders and North African merchants. Kano became increasingly prominent, serving as a clearinghouse for local cloth produced in Borno and Kano, forest products from the south, gold from the southwest, and goods traded across the Sahara by Arab merchants, some of whom settled in Kano and Katsina. Thus, long before colonialism, Kano had already developed a cosmopolitan outlook.

Kano’s final sarki of the fifteenth century, Mohammed Rumfa, embodied Kano’s new status. Rumfa established an Islamic theocracy, encouraged prominent residents to convert to Islam, and invited many Islamic scholars to settle in the city. Among these scholars was Sherif Abdu Rahman from Medina in Arabia, who brought his library and numerous learned followers. During his reign, Rumfa also expanded the Sahelian Gidan Rumfa (Emir’s Palace), built the city walls of Kano, and established the Kurmi Market.

Mali’s Fall, Songhai’s Rise

In the fifteenth century, Mali faced a crisis, leading to the transfer of its power eastward to the new imperial centre of Songhai. Mali’s influence began to decline around 1433–34, marked by the loss of Timbuktu to the Magsharan Tuareg from the northern desert. This retreat signalled the rise of Songhai, with its young king, Sonni ‘Alī, reclaiming Timbuktu in 1468.

For Songhai, the late fifteenth century represented the height of its expansionist power. Sonni ‘Alī waged wars for years, conquering neighbouring kings and regions such as Djenné and Kebbi.

He then developed new administrative frameworks, putting each conquered province under a war chief who recognized his authority, and running a central administration from the Songhai heartland at Gao, where there was an imperial administration and a royal military council. Over time, Songhai’s rulers would develop a complex system of titles, including the bana farma (paymaster general), fari mondoyo (overseer of royal estates), goima- koi (harbourmaster for the river ports on the Niger) and the yūbu- koi (chief of the market.

This intricate administration led to rivalries and conflicts, particularly regarding the role of Islam in the empire. A major controversy surrounding Sonni ‘Alī was his dismissive attitude towards the scholars and holy men of Timbuktu, in stark contrast to his more Islamized successors. He was known for tyrannizing, killing, insulting, and humiliating them. However, Islam would be the glue of the new empire under his successors, and, when Sonni ‘Alī died in 1492, drowned in a river after returning from a military campaign, the place of Islam as a guarantor of trade and external connections would be renewed.

The rise of Songhai was driven by various factors. For one, there was the decline of the western trans-Saharan trading route through Oualata in Mauritania. Demand for gold and enslaved persons increasingly shifted eastward to Cairo and the Ottoman Empire following the capture of Constantinople in 1453. The growing diplomatic ties between Constantinople and Borno aimed to redirect trade in their favour, mirroring the shift of power from Mali to Songhai. Additionally, the arrival of the Portuguese in the mid-fifteenth century further weakened Mali’s control over western trading routes.

After Sunni Ali’s death, Askia Muhammad (also known as Askia the Great) took power in 1493 and led Songhai to its zenith. He expanded the empire further, reformed the administration, and promoted Islam, making a pilgrimage to Mecca that enhanced his prestige.

The Collapse of the Songhai Empire and End of an Era

Throughout the sixteenth century, Songhai’s significance was widely acknowledged. However, by the 1580s, the empire was beset by both external and internal pressures. Following the long and illustrious reign of Askia Dawūd (c. 1549–1582), succession struggles ensued, leading to civil wars in 1586–1588 during the reign of Askia Mohammed IV Bani. Mohammed’s successor, Ishaq II, made efforts to quell the growing divisions between the western and eastern provinces of the empire, but these efforts only led to further fragmentation.

As a result, the empire was weakened and fractured when its overdependence on the trans-Saharan trade began to pose significant problems. Over time, alternative trade routes emerged, reducing the volume of trade passing through Songhai’s key cities like Timbuktu and Gao. This decline in trade revenue undermined the economic foundation of the empire.

At the same time, the Moroccan kingdom was thriving. In 1588, the Moroccans had defeated and slaughtered a Portuguese army led by the Portuguese King Sebastião I, effectively ending any Portuguese territorial claims in Morocco. By late 1590, Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur of Morocco now sought to control the gold trade routes that were crucial to Songhai’s wealth.

In November 1590, the Sultan dispatched the Moroccan Army, which reached Niger at the end of February 1591. At the decisive battle of Tondibi, near Gao, the Moroccan forces equipped with firearms, defeated the larger but less technologically advanced Songhai army, and the Songhai Empire collapsed in civil war.

For centuries, Songhai, and Mali before it, had been the land of gold. Green writes, “The gold trade had been the keystone in the globalization of West Africa, and had influenced events as far distant as the fall of Constantinople and the onset of the Portuguese voyages of discovery… The fall of Songhai represented the end of the first phase in the globalization of West African peoples, states and worldviews.”

Small Group Tour of West Africa for the Adventurous Senior Traveller

Odyssey offers easy, convenient, and relaxed escorted small group tours across the world, including to Ghana, Togo and Benin in West Africa. On our 21-day small group tour West Africa, we explore these three countries’ natural beauty, ancient heritage, World Heritage Sites, and famous cities, all with some truly spectacular scenery along the way. Ghana, Togo and Benin may be off the usual tourist route, but each has much to offer the discerning visitor. Our tour concentrates on the history, culture and wildlife of these African countries. Designed for the senior traveller, It is led by experienced, and enthusiastic likeminded tour leader and guides.

This small section of Africa has a fascinating, if often tragic, past. Colonial powers including the Portuguese, French, Germans and British all fought for control of this gateway into the rich African interior. It was from here that enormous numbers of slaves were shipped to Europe and the Americas from the 16th to the 19th century. On our tour we will visit some of the well preserved “Slave Castles” to witness this infamous part of European history.

The pre-colonial past is also fascinating. Local kingdoms existed from very early times. Our trip explores the culture and history of a number of different groups. In Benin, for example, we will visit the mud tower houses of the Batammariba people. Take time to trace the history of Somba culture in the Natittingou Museum. A Gelede masked dance ceremony will give us an insight into local traditions dating back to the 15th century.

Ghana, Togo and Benin offer a diverse range of cultures and activities in what is actually quite a small region. There are long, palm fringed, sandy beaches, dense rain forests, teeming cities and exotic wild life parks. These countries all suffer from great poverty but each is attempting to escape from their economic hardships through a variety of strategies, including increased tourism. Become a part of the solution!

Odyssey Traveller has been serving global travellers since 1983 with educational tours of the history, culture, and architecture of our destinations designed for mature and senior travellers. We specialise in offering small group tours partnering with a local tour guide at each destination to provide a relaxed and comfortable pace and atmosphere that sets us apart from larger tour groups. Tours consist of small groups of between 6 and 12 people and are cost inclusive of all entrances, tipping and majority of meals. For more information, click here, and head to this page to make a booking.

Articles about Africa published by Odyssey Traveller:

- The Portuguese in Africa

- Discover Central and West Africa: Ghana, Togo, Benin and more

- Exploring South Africa: The Definitive Guide for Travellers

- Madagascar’s Fascinating History

- Questions About Egypt for Senior Travellers

- Africa’s Gold Coast and the Gold Trade

For all the articles Odyssey Traveller has published for mature aged and senior travellers, click through on this link.

External articles to assist you on your visit to West Africa:

Related Tours

21 days

May, SepExplore the History, Culture & Wildlife of West Africa: Ghana, Togo & Benin

Visiting Benin, Ghana

This small group tour for couples and solo travelers concentrates on the history, culture and wildlife of coastal Central Africa. Meet the friendly local people and come to a greater understanding of just what has made them what they are today.

From A$14,995 AUD

View Tour

18 days

Nov, JanEgypt tour: escorted small group history & cultural tour of Egypt

Visiting Egypt

Our small group program for senior and mature couples and solo travelers takes us to contemporary feats such as the Aswan Dam and also to current crucibles of the Egyptian experience such as Tahrir Square. Proof, were it needed, that Egypt’s role as the pivot of civilisation is far from ended. There is the opportunity to visit our Morocco, Jordan or Iran tours before embarking on this tour of Egypt.

From A$12,950 AUD

View Tour

16 days

Apr, Aug, SepMadagascar Small Group Tour | The island of Lemurs & Avenue of Baobabs

Visiting Madagascar

On this small group tour we explore the country’s natural wonders as well as its colonial past. Madagascar has a range of extraordinary plant and animal life which we will have the chance to view in the island’s National Parks and Nature Reserves. While on the tour we will also learn about both the Portuguese and French periods of control.

From A$14,295 AUD

View Tour

10 days

SepNamibia Wildlife and Culture Tour for Seniors

Visiting Namibia

A small group tour for seniors and couples to Southern Africa for couples and solo travellers. Namibia shares borders with Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Wedged between the Kalahari and the South Atlantic, Namibia is home to the oldest desert of the earth. Despite its parched reputation, Namibia is one of the world’s best wildlife destinations.

From A$11,695 AUD

View Tour

20 days

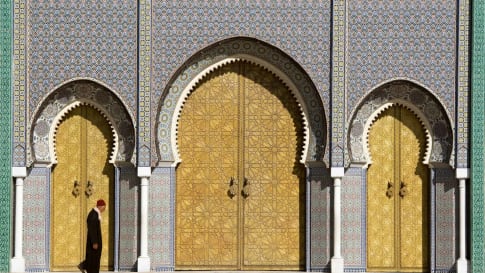

Apr, Oct, MarMorocco tour for senior travellers

Visiting Morocco

Embark on an unforgettable journey through Morocco: A Gateway to a world of vibrant colors, cultural diversity, and endless wonder. Join our escorted small group tour designed for senior travellers, whether you're a couple or a solo adventurer, and immerse yourself in the captivating allure of Casablanca, Fez, Meknes, Rabat, Marrakech and beyond. Experience the richness of Moroccan traditions and heritage as we explore this enchanting destination.

From A$11,915 AUD

View Tour

19 days

AugSouthern Africa Tour | Fully Escorted Africa Tour for Seniors

Visiting Botswana, South Africa

Experience as a small group tour for couples and solo travellers, the beautiful landscapes of the Garden route and the unique wildlife at places such as Kruger National Park, Cape Town, Victoria Falls and Chobe Game Reserve. During the program participants will have the opportunity to learn about the culture, the politics and the social issues facing South African people in Soweto and more. How the natural resource managers are caring for their wildlife reserves in the face of land enclosure, climate change and poaching.

From A$12,095 AUD

View Tour

14 days

Apr, Sep, MarTour of Tunisia

Visiting Tunisia

Join Odyssey Traveller on this small group tour of Tunisia in North Africa for couples and solo travellers, where Carthaginian ruins sit side by side with Roman monuments, grand Islamic mosques, Arabic souks and medina, and honeycomb-like Berber cave dwellings and hilltop villages.

From A$10,995 AUD

View TourRelated Articles

Africa's Gold Coast

Article for travellers exploring West Africa and Ghana about the Portuguese and Gold. An Antipodean travel company serving World Travellers since 1983 with small group educational tours for senior couples and mature solo travellers.

Atlantic Triangular Slave Trade

Atlantic Triangular Slave Trade Somewhere between ten million and twelve million enslaved Africans were transported across the Atlantic to the Americas between the middle of fifteenth century and the end of the nineteenth. The largest…

Caves of Hercules, Morocco

Visit the cave of Hercules whilst on a Small group package tour of Morocco for mature and senior travellers. Morocco is an ancient country with a fascinating history too be explored by couples and single travellers.

Elements of Mosque Architecture

The word "mosque" often brings to mind not this simple prayer space, but the ornately decorated monuments built by powerful Islamic rulers.

Exploring Ancient Cities

Exploring Ancient Cities What can we learn from exploring the ancient world? What do we take away from the wealth of knowledge uncovered as archaeologists investigate the ruins of past societies, while social scientists speculate…

Exploring Southern Africa: The Definitive Guide for Travellers

Exploring Southern Africa Southern Africa, a subregion of the African continent, is composed of Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. (The United Nations geographic region of Southern Africa, on…

Marrakech, Morocco

Marrakech's medina quarter is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a dazzlingly colourful maze of alleyways and shops, the sights and sounds welcoming and enchating travellers.

Portuguese in Africa: The Definitive Guide

The Portuguese in Africa The Kingdom of Kongo and the Transatlantic Slave Trade The Kingdom of Kongo was a former kingdom that dominated West Central Africa in the fourteenth century (Heywood, 2009). Located south of…

The Phoenicians and Purple Dye

Article supporting tours to Morocco, Tunisia, Spain, Sicily and Crete. The Phoenicians where one of the empires controlling the Mediterranean sea from the 11th to 13th century. This article is for small group educational tours for senior couple and mature solo travellers joining a program.

Early History of Sicily: From the Phoenicians to the Arab Conquest

Early History of Sicily: From the Phoenicians to the Arab Conquest (800 BC to the 10th Century) Sicily in Southern Italy is the largest island in the Mediterranean, separated from the mainland by the Strait…

Empires Crossing the Mediterranean: 1130-1300

As a sea connecting continents and stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Asia in the east, the Mediterranean has for centuries been a centre of trade and exploration.

History of Genoa, Rival to Venice

In this article, we will look at the history of Genoa, and its rivalry with Venice that led to several wars fought between the two city-states in the 12th to 14th centuries.

Atlantic Ocean and How it Shaped Ancient Communities In Europe

Article of interest for senior couples and mature solo travellers joining a small group European tour to Faroe Islands, Scottish Isles, Morocco or Portugal. Focus is on the early exploration of the Atlantic.