Traveller's Guide to Medieval England

A travellers guide beyond the landscapes of Medieval England supporting Britain's history from the Roman's to Queen Victoria and the industrial revolution.

18 Sep 21 · 14 mins read

A Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England

A myth commonly repeated about the medieval world is that ordinary people never travelled more than five or six miles from their home. In reality, this was far from true – travel was an important part of daily life in medieval England. People travelled around England and sometimes went abroad for a number of reasons: trade, shopping, religious pilgrimages, and war.

Much like travel today, travel in the Middle Ages came with a number of difficulties: unreliable modes of transport, uncomfortable accommodation, and the dangers posed by bandits and other criminals.

Imagine that you were planning to travel in Medieval England. Whether your purpose was business or trade, or you were making a religious pilgrimage, you would probably have a number of questions. What route should I take? Where should I stay? What difficulties might I encounter on the way?

In this article, we use the format of one of our travel guides in order to immerse the reader in the experience of travelling in the Middle Ages. We have drawn information from Ian Mortimer’s vivid history of 14th century England, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England.

This is part of our collection of England-related articles that we share as backgrounders before you go on a England tour with us, or to simply help you as you firm up your travel plans. All of those articles can be found here.

Travellers with a particular interest in the Middle Ages might be interested in our previous articles on the topic: Village Life in Medieval Britain and Understanding British Churches.

How should I get from place to place?

Getting from place to place (for instance, to use Mortimer’s example, from London to Chester) in medieval England posed a number of difficulties. Firstly, you would have had to work out what route to take. This was made more difficult by the fact that you wouldn’t have had a map. While there were maps in the Middle Ages, these were reference works for use in libraries and households, made of heavy parchment. You certainly wouldn’t have been able to toss one in your bag to consult on the way!

The best way to find your way would have been to ask for directions. You’ll find that the locals have a good memory for places, landmarks, and routes. Directions are usually given as an itinerary, such as:

On the right hand, when ye come to a bridge, so go there over; ye shall find a little way on the left hand which shall bring you in a country where you shall see upon a church two high steeples. From thence shall ye have but four miles unto your lodging. (From a Medieval dialogue book).

Next, you would need to think about what mode of transportation you might take. The two major ways to travel are by road or by sea, each of which has a number of drawbacks.

Road:

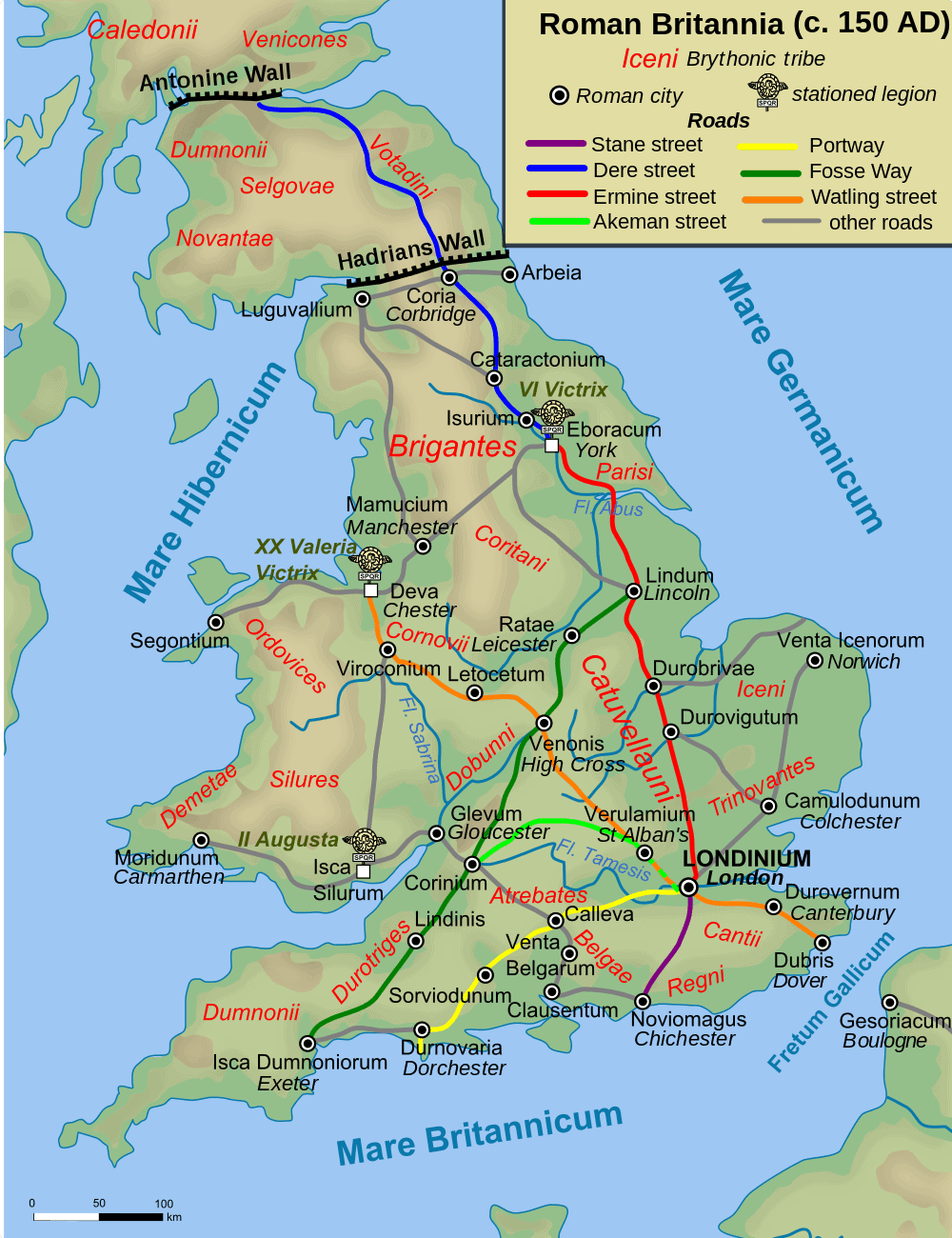

Travel by road in the 13th century continued along the great roads established by the Ancient Romans, including Fosse Way, Ermine Street, Watling Street, and Icknield Way. The main highways are usually kept in good repair, especially when the King travels along them.

However, don’t imagine the smooth and straight roads of the Roman era. While in some places the ancient stones were still in place, in others they have been taken away for use in new buildings. In many places the old roads are now bumpy and uneven – in which case, we advise you take the smoother medieval road that might run alongside it. Some of the most popular destinations in medieval England – the university town of Oxford, the rich market town of Coventry, or the entire country of Cornwall – are not on the Roman network.

In more remote areas, the roads were less well-kept. In bad weather, they might be flooded with water – or farmyard debris let out of a latrine pit.

Moreover, if you encounter a river, there’s no guarantee of a bridge to cross it easily. While on the highways most rivers are spanned by smooth stone structures, when you get off the main road your options were usually either a wooden bridge or the old ford. Some of the old bridges are so rickety that you might find the ford preferable, even if it means that you get wet. In hillier or highland areas bridges are few and far between. Bear in mind, too, that you might have to pay a toll to cross.

The main transportation options for travel by road are:

- Horse. By far the most common option. While royal messengers can reach speeds of 80 miles/day, we advise that mature and senior travellers should not expect to travel more than ten miles per day.

- Cart/wagon. Generally used for goods (not people). Not advised as speeds are very slow and transport is uncomfortable.

- Coach. A rare option reserved for the wealthiest people (generally female members of the royal family or older noblewomen). If this is an option for you, we recommend it, but bear in mind that this will be expensive. Expect to pay up to a thousand pounds for your coach.

- Litter. Another option preferred by aristocrats. Two long poles carry a seat, supported by two horses, one before and one after. The seat has a round canopy to protect travellers from the ailments. Motion-sick travellers should beware, however – litters have a tendency to rock from side to side, particularly if the horse encounters uneven territory.

Sea:

The other major option is travel by sea. Make sure to check up on the political situation before you leave, as English boats are commonly held hostage by French and Flemish sailors during periods of hostility. Even in peacetime, you may be at risk of attack from pirates.

Even leaving aside the dangers, sea travel could be unpleasant. Few people washed at sea, food did not keep well, and it was impossible to keep the boat dry during a storm. Expect to be wet and miserable – and possibly sea sick. In close quarters with your fellow travellers, expect them to begin to grate on you. Make sure, however, not to get into a physical fight – or else you might see yourself tied up with rope, and dunked three times into the sea, according to the old sea-laws of Richard I.

Where should I stay?

Several types of accommodation are commonly found around medieval England:

Inns:

Inns are the major commercial form of accommodation open to travellers. Don’t expect luxury or even a friendly welcome, however – most inn-keepers are no-nonsense men, used to dealing with thieves, ruffians, and other trouble-makers. While in some towns, the law requires inn-keepers to offer every visitor a bed, in others they have the right to reject you. To ensure that you will be accommodated, we advise that you send a servant on ahead to make inquiries on your behalf.

One of the highlights of an inn is the common hall where travellers gather by the fire to drink ale, eat bread and cheese, and exchange stories with others. However, make sure to choose your inn wisely. While a good establishment will change the floor rushes regularly, and weave these with lavender, rose petals and herbs, the worst rarely change them – so you can expect a stench of mouldy food, mud and horse dung trodden in from the street.

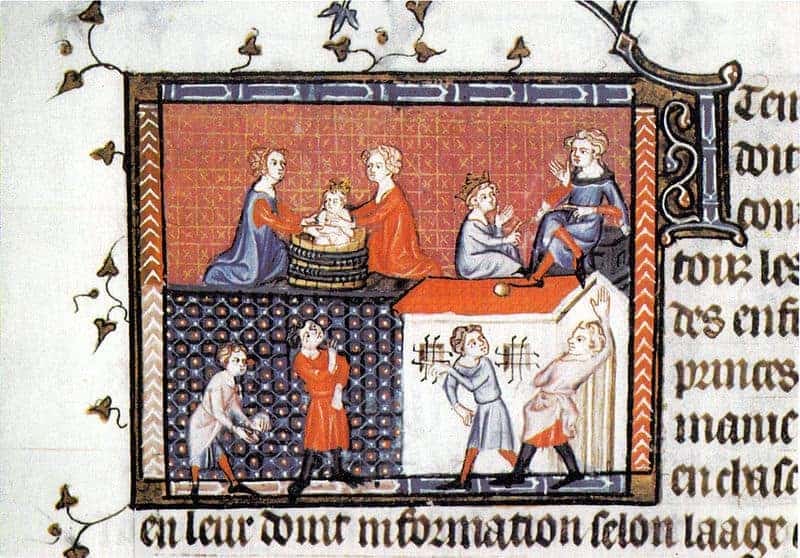

At night, you will sleep in a bedchamber that is home to several beds, each of which holds two to three men. Women are expected to lodge in the same chambers, though it is rare for a woman to stay at an inn alone. Expect a straw mattress, and, at the best establishments, a chest for personal possessions and a pitcher of water for washing.

For more on British inns, taverns, and alehouses, take a look at our article on the history of the British pub.

Monasteries:

Most travellers in medieval England can expect to stay at a monastery at some point. All religious houses offer hospitality as a part of their Christian duty. The extent of this hospitality, however, tends to vary according to your social standing. If you’re a nobleman, or part of the higher clergy, you can expect to share the abbot’s lodgings. Travellers arriving on horse may stay in the guesthouse; while those arriving on foot are generally directed to the dormitory to share in the accommodation of pilgrims and the itinerant poor.

If you stay in the guest house, expect comfortable but simple accommodations. Most guest houses are not decorated. Like at an inn, you will sleep on a straw mattress. Monasteries do have advantages over inns, however, primarily sanitary. Unlike inns, many monasteries have efficient systems of providing clean water for washing, drinking, and cooking, and even flushing drains.

Private houses:

It is also likely that you will stay in a private house at some point. Most people in medieval England are hospitable, and understand the difficulties of travel. Hospitality is considered a work of charity, and most locals are happy to hear a stranger’s news over a mug of ale and plate of bread and cheese.

Where you find this hospitality might depend on your social status, however. If you’re a peasant, you’ll likely only find hospitality with fellow peasants, while a lord is welcome everywhere. The quality of the accommodation will reflect the social status of your host. In a castle or a rich townhouse you can expect a comfortable feather bed with linen sheets. At a peasant’s house, however, you’ll find that accommodation is much more modest – you’ll probably receive a straw- or oat-stuffed mattress, laid out in the family bedchamber. You can trust that the hospitality will be genuine, though. Expect to spend the evening swapping tales with your host over the main meal.

What should I eat?

Don’t expect that many of your favourite foods will be available: prior to the colonisation of the Americas, products we now take for granted such as potatoes or tomatoes were not available in England. Remember, too, that there are strict rules around eating meat – the Church forbids the consumption of meat on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, and throughout Lent and Advent.

Most likely, you will be invited to eat with the locals. At a country peasant’s house, expect the meal to include rye bread and pottage – porridge with peas, herbs, some bacon, and white beans. In town, look out for white bread, fresh fruit, and spices. We also encourage you to try the street food, particularly the hot pies and pastries regularly sold at markets.

Since the water is often of dubious quality, alcoholic beverages are served with each meal. These include:

Ale: You’ll likely be offered this if you dine with a peasant. Made from malted barley or oats, without any hops, most ale is brewed in the home and only lightly alcoholic (a good thing, since many peasants and labourers go to work after drinking it).

Cider/perry (pear cider): Often drunk instead of ale in the western counties, cider is more likely to be highly alcoholic, and often retails for half the price of ale.

Mead and metheglin: Alcoholic drinks based on fermented honey, mead and metheglin (mead flavoured with herbs and spices) are largely drunk in the west and south. Like cider, these drinks are more affordable than ale and much more alcoholic.

Wine: Though generally beyond the means of the typical yeoman farmer, wine is more affordable in town, where tavern-owners buy in bulk. Wine served in taverns is usually imported from Bordeaux, Spain, or the Rhine region, but if you travel in the early part of the 14th century you may have the chance to taste an English wine. In the early part of the century, many noble and royal houses had extensive vineyards, but a changing climate (by 1400, the annual average temperature had dropped by 1 degree from 1300 averages) led to the destruction of the English wine industry.

What should I wear?

The 14th century saw the people of England become increasingly fashion-conscious. James Laver, a fashion historian, has suggested that the 14th century marks the beginning of recognisable ‘fashion’ in clothing. At the beginning of the century, women and men alike wore simple tunics that hang from the shoulders; status was indicated by the quality and colour of clothing, rather than cut. By the end of the 13th century, clothing had become figure-hugging, cut to display the lines of the body.

It was men’s clothing which saw the most drastic transformation. At the start of the century, men wore tunics which reached the floor; by 1400, this had become a doublet that ended at the hip, leaving the legs covered only in hose. Observers were scandalised: a French chronicle remembers that

‘Around that year (1350), men, in particular, noblemen and their squires, took to wearing tunics so short and tight they revealed what modesty bids us hide. This was a most astonishing thing for the people’. (Continuation of a chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis, quoted by Braudel, 1981).

Men’s shoes also become increasingly outlandish. While relatively modest at the beginning of the century, the toes became increasingly prolonged as the century progressed. By 1350 most toes were six to eight inches long, with the Crackow style – imported from Bohemia – reaching twenty-inches. Male travellers wary of the daring doublets of late 13th century England may find the dress of the clergy, which changed little from the beginning of the century, more congenial.

Though women’s dresses became more figure-hugging, they remained relatively modest. Women travellers should remember to dress modestly: ‘respectable’ women in the 13th century always covered their arms and legs. While women had long hair, it was never worn loose in public, and married women covered their hair.

Travellers to medieval England are also advised to research the sumptuary laws of the city they wish to visit. These are laws which restrict people from dressing above their station: so for instance, in 1337, a law was passed providing that only those with an annual income of 100 pounds per year are allowed to wear furs.

What should I buy?

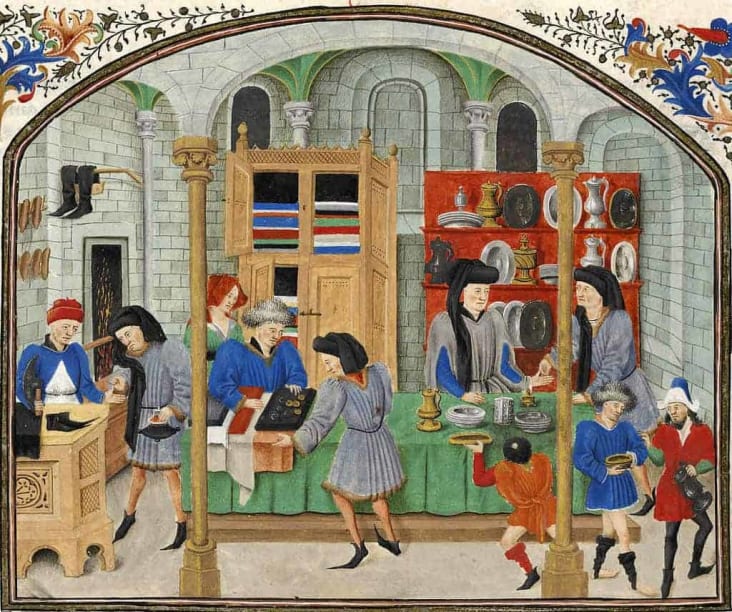

One of the highlights of any visit to medieval England is a trip to market. Small towns and cities alike have markets, though in the smallest villages you shouldn’t expect much beyond fresh produce and practical hardware for home use – nails, hay, carts, and coal. If you’re lucky, you might encounter a travelling fur shop where people stock up on warm clothes for the winter. In bigger cities, you’ll find specialist stores where you can buy clothing, shoes, armour, jewellery, and cosmetics and medicines.

For the best shopping experience, time your visit with the annual fair. Most market towns have a fair, usually held on a feast day between July and September. Here, you can pick up some exotic, imported goods – spices; fruits such as oranges, lemons, figs, dates, and pomegranates; and luxury silks.

Watch out for tricks and deceptions when shopping. Common tricks include loaves of bread with iron inside them (so that they meet their legal weight), cloth mixed with human hair and cooking pots made out of soft, cheap, metal. If you feel like you’ve been ripped off, think about reporting this to the local Tradesman’s Guild – they have an interest in protecting their markets from competitors, so want to keep their good reputation.

How do I greet the locals?

Manners are very important in medieval England. Make sure to show respect to your social superiors. If you are invited to someone’s house, leave your weapons at the door, take off your hat, and when introduced, bow (if you are of equal status to them), or kneel (if they are of superior status).

If you run into a friend on the street, make sure to greet them. If they are a woman, doff your hood. Acceptable greetings include:

Sire, God you keep!

Sire ye be welcome.

Yea, lady or demoiselle (damsel), ye be welcome.

Sire, God give you good day.

Dame, good day give you our lord.

Is it safe to travel to Medieval England?

While it was perfectly safe to travel in Medieval England, travellers should be advised that they might confront certain dangers on the journey. In particular, solo travellers are often the victim of robbery by armed bandits. While the law requires that the road be cleared of trees on both sides of the highway for a hundred yards (to prevent the sneak emergence of bandits from under foliage), this is not always observed. We recommend you join with a group of other travellers or pilgrims to ensure that you reach your destination safely.

We also recommend that you avoid the areas of ongoing conflict near the Scottish border, particularly the counties of Cumberland and Northumberland. Here, large sections of the landscape have been abandoned due to population decline in the wake of the Great Plague. The area is also subject to frequent incursions from invading Scots.

What is there to do?

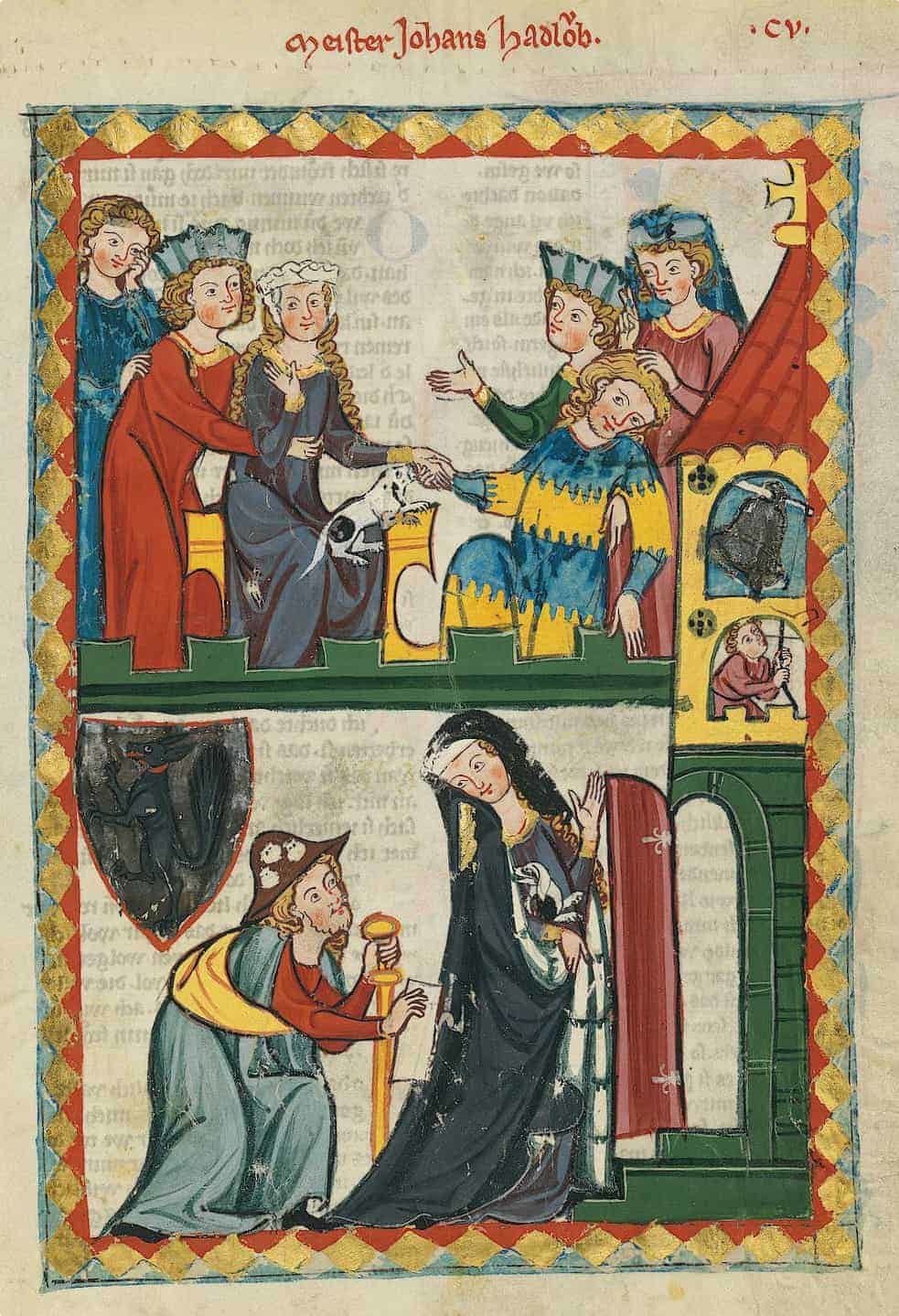

The people of medieval England enjoy a number of leisure activities. You might enjoy a musical performance; itinerant troubadours commonly visited the halls of great lords and performed for their fellow travellers. Dancing is popular with people of all social classes, and feel free to sing along with the music – many people did.

You may also witness a play. Most common are miracle plays and mystery plays, performed on feast days in major towns. The plays performed at York, Chester and Wakefield are known around the kingdom. Also popular are the more secular mummers, in which the emphasis is less on the story and more on characters, exemplified by the lavish masks worn by the performers.

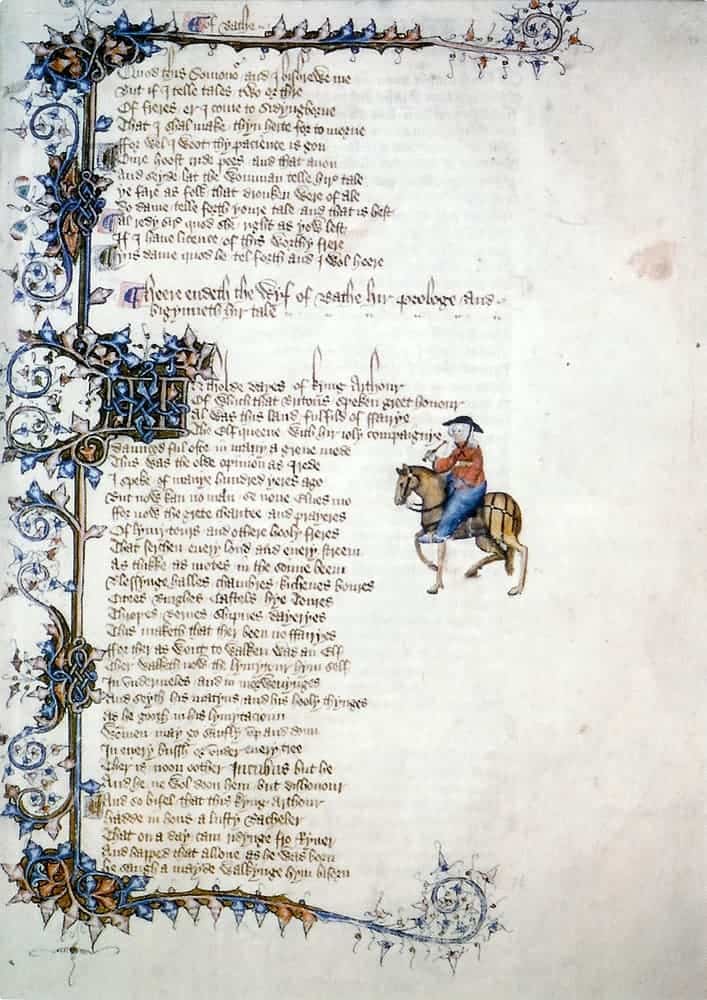

Other cultural activities include reading and the telling of stories. While few people are literate, and even fewer have access to manuscripts in this pre-printed press age, books are often read out loud and minstrels travel the countryside, telling stories to those who cannot read. Works of literature put down in the 14th century are still read today, particularly Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

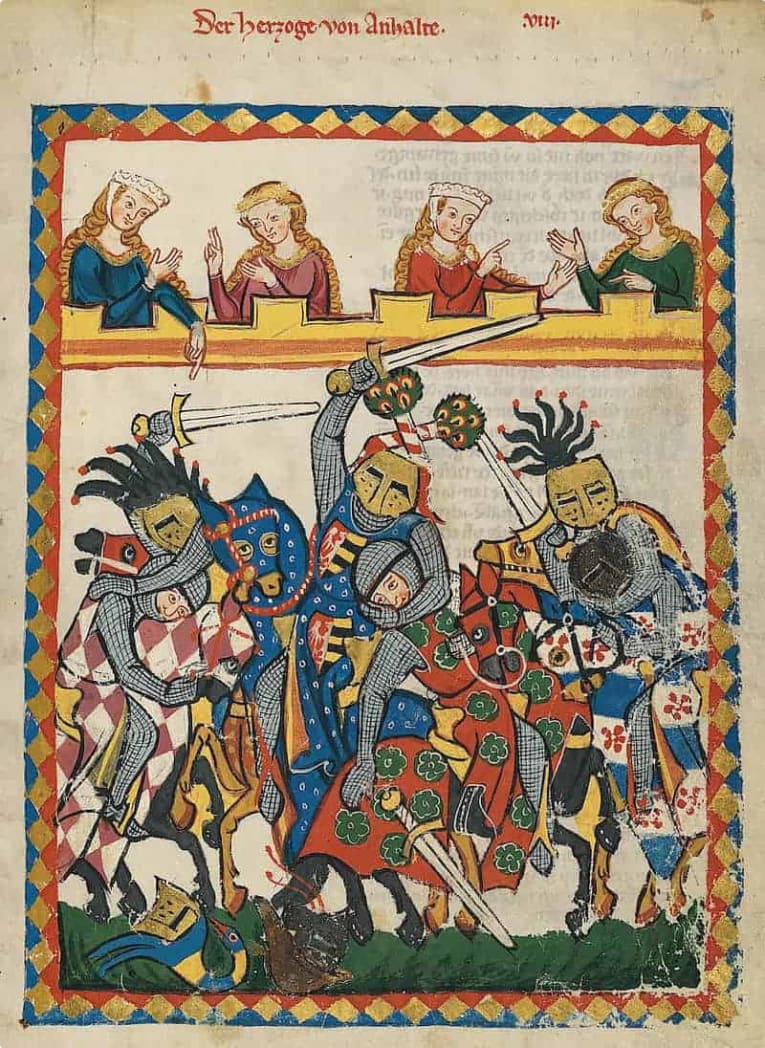

Travellers might also want to check out some distinctive medieval sports at a tournament. The tournament is believed to originate with a French baron, Geoffroi de Pruelly, around the middle of the 11th century. The first tournaments centred around the melee, or a mock battle between two groups of armed horsemen. These could be dangerous: in 1241, eighty knights were killed in a single tournament! By the early 14th century, melees were much more orderly, performed solely for the benefit of spectators.

Beginning in the 1330s, the melee became a thing of the past. Increasingly popular was the joust, in which two horsemen charged at each other with lances, with the aim of knocking the other of their horse. The lances used in jousting were capped, making the sport relatively safer than the melee – while combatants occasionally lost their life if they fell in a bad direction, for the most part, injuries amounted to little more than bruising, loss of teeth, or broken bones. Jousts were popular occasions, attended by huge crowds, who used the events to eat, drink copiously, and flirt with fellow attendees.

Some contemporary sports also have their origins in medieval England. In the late 14th century, a sport known as ‘tennis’ was introduced to England. Unlike today’s sport, medieval tennis was usually played inside – sometimes with rackets, and at other times with the palm of the hand.

You might also come across a sport described as:

‘adominable … more common, undignified and worthless than any other game, rarely ending but with some loss, accident or disadvantage to the players themselves’.

This is soccer. While that description might sound extreme when thinking about the modern game, most medieval games of football were more akin to a melee without weapons than anything resembling contemporary soccer. The game was banned in London in 1314, and throughout the kingdom in 1331 and 1363. If you encounter this game, we do not recommend you join in.

We hope you enjoyed this immersive guide to 14th century England. Travellers with a particular interest in the medieval era might want to join our small group tour of Medieval England. This tour is one among many devoted to the history and culture of England – take a look at the full list.

You might also be interested in our summer school devoted to Medieval and Renaissance Women.

Related Tours

22 days

Apr, SepSmall group tours Medieval England

Visiting England

A small group tour of England focused on Medieval England and Wales. Spend 21 days on this escorted tour with tour director and local guides travelling from Canterbury to Cambridge, passing through Winchester, Salisbury, Bristol, Hereford and Norwich along the way. Castles, villages, Cathedrals and churches all feature in the Medieval landscapes visited.

From A$14,665 AUD

View Tour

19 days

Jun, SepEngland’s villages small group history tours for mature travellers

Visiting England

Guided tour of the villages of England. The tour leader manages local guides to share their knowledge to give an authentic experience across England. This trip includes the UNESCO World heritage site of Avebury as well as villages in Cornwall, Devon, Dartmoor the border of Wales and the Cotswolds.

From A$16,995 AUD

View Tour

16 days

JunBritish Gardens Small Group Tour including Chatsworth RHS show

Visiting England, Scotland

From A$16,895 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Sep, JunRural Britain | Walking Small Group Tour

Visiting England, Scotland

A walking tour into England, Scotland and Wales provides small group journeys with breathtaking scenery to destinations such as Snowdonia national park , the UNESCO world heritage site Hadrians wall and the lake district. each day tour provides authentic experiences often off the beaten path from our local guides.

From A$15,880 AUD

View TourRelated Articles

Understanding British Churches: The Definitive Guide for Travellers

British Churches Through the Years “How old is this church?” asks Mary-Ann Ochota in a chapter of her book, Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape (Francis Lincoln, 2016, p. 250). In this article, we…

Touring England's villages

Touring England’s villages For many travellers, London is synonymous with England. This lively, cosmopolitan capital is a must see, of course, but there is more to England than booming cities and industrial centres. Instead, what…

Studying Gargoyles and Grotesques: The Definitive Guide for Travellers

Article to support world travellers since 1983 with small group educational tours for senior couples or mature solo travellers interested in British and European history.

Medieval British Village Life: The Definitive Guide for Seniors

Life in the Medieval British Village In a previous article, we looked at the icons of the British village–the pub and the cottage–and looked at their history and evolution from Roman and Norman times. In…

Lumps and Bumps: How to Read the British Landscape

The British landscape has been worked and re-worked. It is secrets of this palimpsest landscape is revealed through drainage patterns and prehistoric features all the way through to the modern day. These small group tours for mature and senior travellers examine the landscape from the Neolithic, to Roman, through the seven ages of Britain in walking tours and history tours of Britain.

Landscapes of Medieval England

Article about Medieval England supporting Britain's history from the Roman's to Queen Victoria and the industrial revolution.