Venice and the History of Maps

Venetian Maps and How they Ruled the World ‘Venice was always a frontier,’ Peter Ackroyd (2009) declares in Venice: Pure City. ‘When the empire was divided in the time of Charlemagne, the lagoons of Venice…

9 Dec 19 · 9 mins read

Venetian Maps and How they Ruled the World

‘Venice was always a frontier,’ Peter Ackroyd (2009) declares in Venice: Pure City. ‘When the empire was divided in the time of Charlemagne, the lagoons of Venice were ascribed neither to the west nor to the east…in the medieval period the postal service provided by Venetian galleys was the only means of communication between the courts of Germany and Constantinople.’ (pp. 350-351).

It was this unique historical and economic vantage point that made Venice an important centre of the map trade during the European age of exploration. The map trade, which helped drive maritime exploration, created a ‘new international trading economy'(Ackroyd, 2009, p. 220) and held ‘a particularly significant place in the daily life of early modern Venice’ (Cosgrove, 1992).

Venice, a major maritime power by the 10th century and commanding the largest merchant fleet in Europe, required accurate charts for trading and shipping, making cartography an indispensable scientific and artistic endeavour in the region during the Renaissance.

In this article, we will look at how Venetian cartographers rose to prominence and how maps became a status symbol in Venice and brought great wealth to the city.

Seafaring, Trade, and Venice

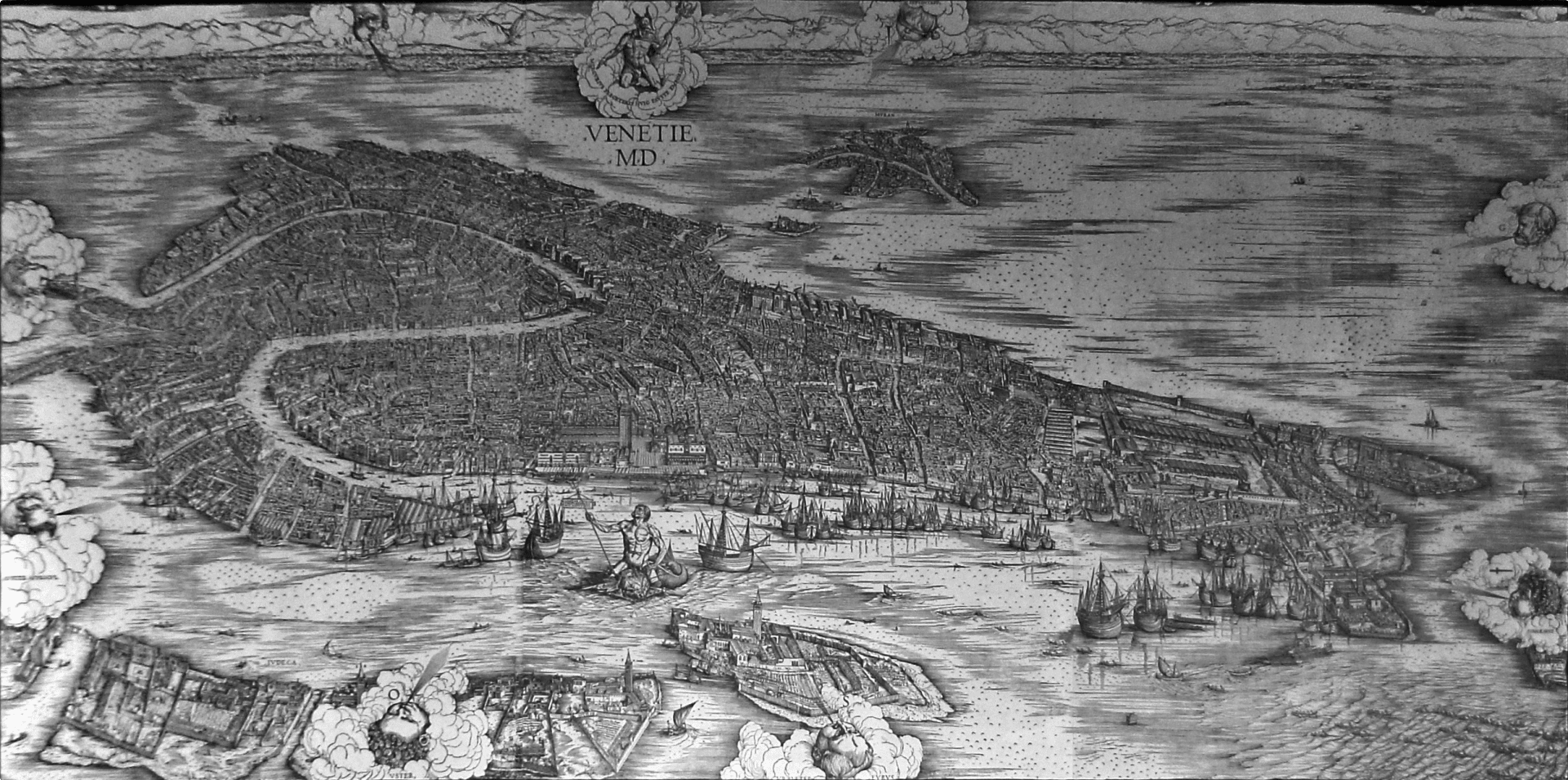

The most famous map of Venice (Ackroyd, 2009, p. 345) was a woodcut engraving by Jacopo de’ Barbari produced in 1500, showing Venice’s “effortless wealth resting on a mastery of trade and navigation”, as Roger Crowley writes in “The Genius of Venice“. The incredibly detailed woodcut shows a bird’s-eye view of the city-state, watched over by the Roman gods Mercury, god of commerce, and Neptune, god of the sea.

It is amazing to think how Venice grew so prosperous, given that it ‘could produce nothing’ (Crowley, 2015). As the city was created on reclaimed land on the lagoon, Venice could not create an economy based on agriculture – they had only fish and salt.

Venetians had to use their ingenuity and innovation to survive and recognised that the sea connected them to the rest of the world. For this reason, they poured their energies into building the best merchant ships and war galleys. Crowley shares that in 1574, to impress the French king Henry III, Venetian workers ‘assembled a complete galley during the length of a banquet’. Trading was a way of life; there was no merchant guild because virtually everyone in Venice was a merchant.

Venetians were encouraged to bring home not only raw materials for production and trade but also innovations and new technology with the state even actively sponsoring industrial espionage. (Read more in our article, ‘Secret Venice‘.)

The development of printing in the 15th century was a turning point. Within half a century of printing’s introduction in Europe, Venice had almost cornered the market (Crowley, 2015). With printing, Venice, in addition to galleys, glass, silk, and spices, found another valuable item that the rest of Europe was eager to buy and which they could sell to create more wealth: printed material – that is, books and, eventually, maps.

Ptolemy’s Geography

Let’s step back in time for a moment.

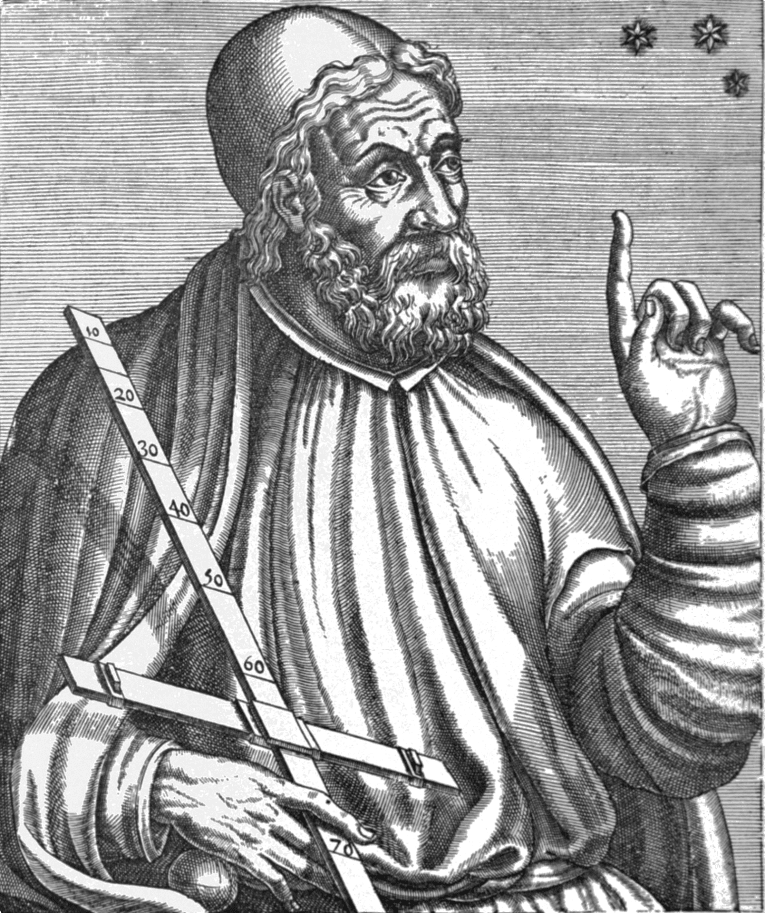

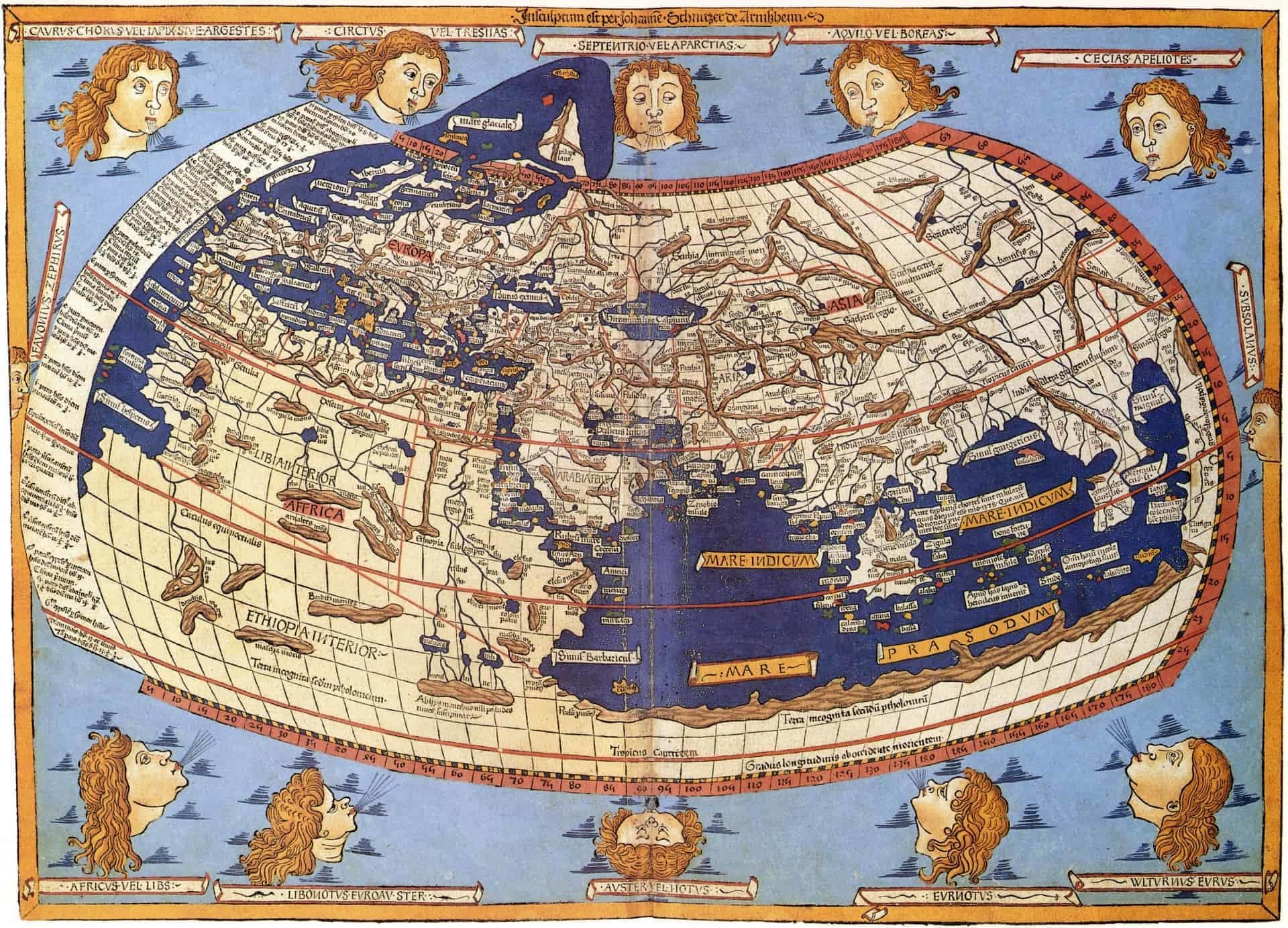

Of great influence on geography in general, and Venetian cartography in particular,is Ptolemy’s eight-volume Guide to Geography (Geōgraphikē hyphēgēsis). Originally written in Greek by Claudius Ptolemy at Alexandria, based on the writings of Marinus of Tyre, this atlas and treatise on cartography provided instructions on how to create maps, as well as several detailed maps of the known world (at least the world known to the Roman Empire) circa the 2nd century.

Ptolemy’s focus on representing the world as accurately as possible helped push scholars to study map construction, but he also made mistakes. For one, Ptolemy was a proponent of the geocentric or Earth-centred model of the solar system (later debunked by Copernicus), and he underestimated the size of the earth, leading to him overestimating the size of Europe and Asia.

But so incredible was his influence that his maps would end up in Italy and later be used by Christopher Columbus, thirteen centuries after Ptolemy poured over the pages of his atlas in the Library of Alexandria.

The Beginnings of Cartography

Ptolemy’s Geography was translated into Arabic in the 9th century and was used by Islamic cartographers. In 1154, Al-Idrīsī created a world map for King Roger of Sicily, probably the first Arabic to Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography, though no copy of it survives.

Before Ptolemy’s Geography was rediscovered in Europe, there was no one orientation used for creating maps. Maps at the time were not the general reference items we know today; in the Middle Ages, they were made for ‘limited purposes, with one class of user in mind’, for example a navigator or simply a traveller who wanted to know more about a place’s customs (Harvey, 1991). What would be shown on the map would depend on its intended purpose – and if in modern times we see these old maps without an inkling of their purpose, they just look odd and useless.

Instead of geographic representations, many of them contained written descriptions, like the ‘map’ created by Sigeric, the 10th century Archbishop of Canterbury, who wrote down details of his route from Canterbury to Rome to receive his pallium (liturgical vestment) from the Pope in 990. His map/itinerary survives now as a guide for the Via Francigena pilgrimage.

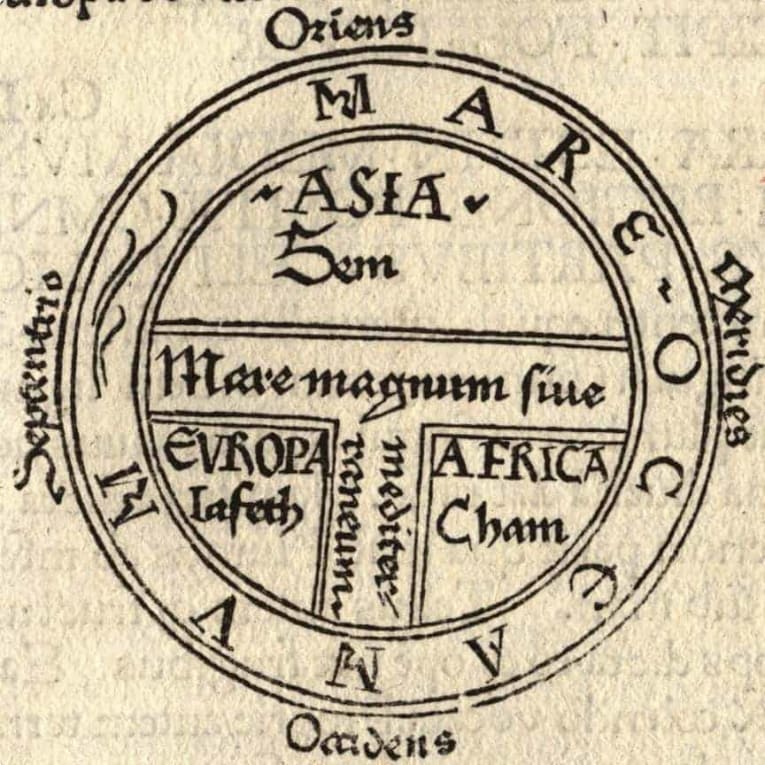

Common among Europeans in the Middle Ages was the small T and O map (T-O or O-T map), called as such because of the way it was rendered: a T inside an O. The O represented the oceans surrounding the world, and the T represented the great bodies of water – the Mediterranean, the Nile, and the Don – dividing the three continents, Asia, Europe, and Africa. Jerusalem was usually at the centre, with the east at the top of the map (evident in our use of the word orientation; Orient = east).

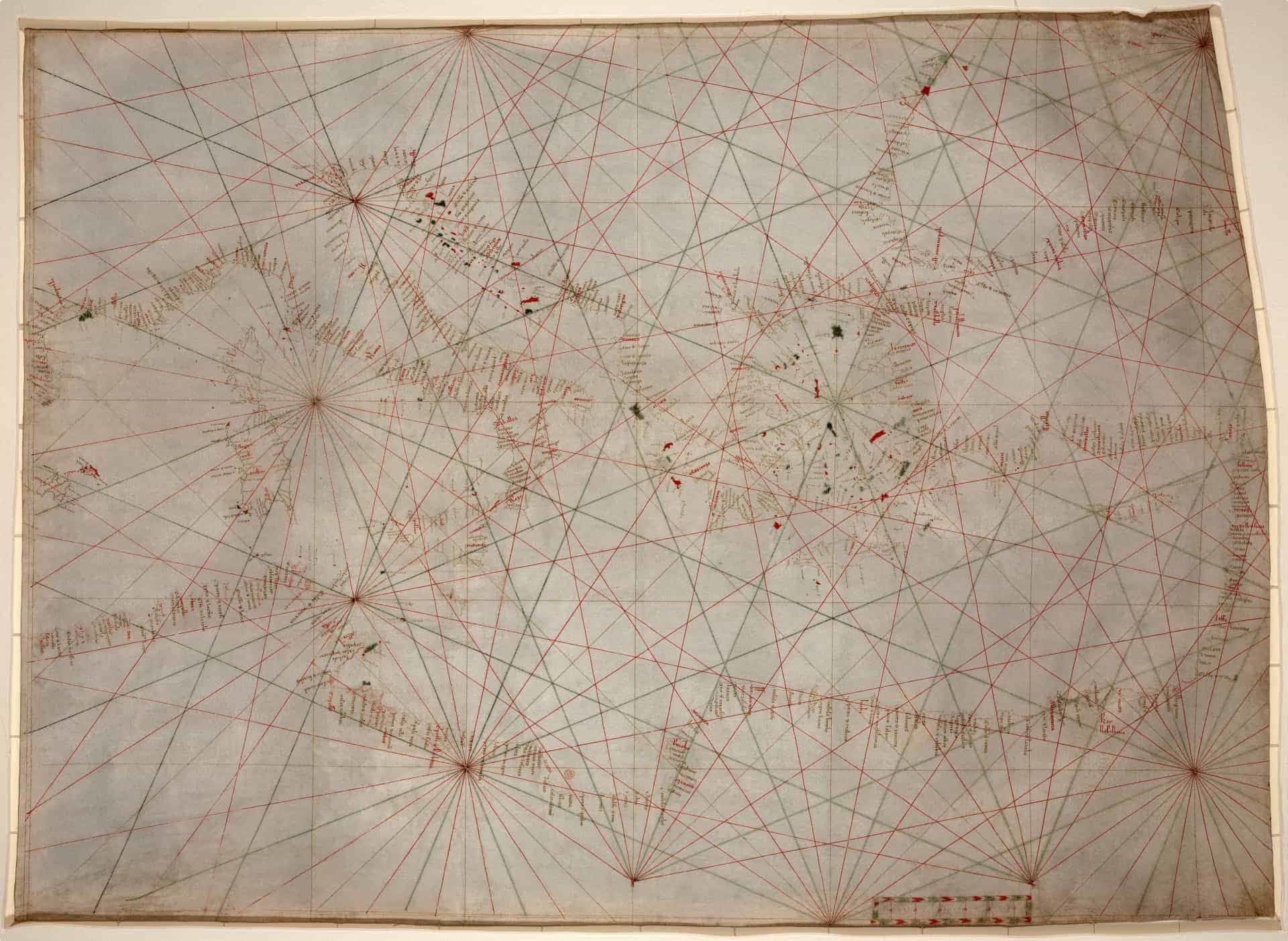

Many of the surviving maps from Europe in the Middle Ages were portolan charts, used for nautical navigation from the 1300s to the 1500s. Most of the roughly 130 extant portolan charts were made in Italy. Portolan charts showed rhumb lines, or lines that radiate from the centre indicating wind direction, and a detailed survey of the coasts and ports.

The Italian charts tended to include only western Europe and the Mediterranean basin, with no details regarding inland topography. (Catalan portolan charts were a bit more detailed.) Early charts were hand-drawn on vellum, a type of high-quality parchment made from calf skin, and were probably “library copies“, never meant to be taken to sea.

Marco Polo and Maps in Venice

The 13th century also saw the travels of the Venetian Marco Polo, who chronicled his travels through Asia and stimulated the imagination of Venetian travellers, as well as the sale and circulation of maps.

As Ackroyd says, the spirit of travel ‘was always part of Venetian consciousness’ (p.350) and it is particularly evident in the Polo family. It is not clear whether the Polos were Venetian nobles, but it is clear that they were extremely wealthy: Marco Polo’s family traded with the Middle East and acquired considerable wealth and prestige. They foresaw the political change in Constantinople, then capital of the Latin Empire after its capture by Crusaders, and liquidated their assets. They travelled to the Volga River, where they had friendly relations with Berke Khan and the Kublai Khan. The Polos returned to Europe wealthier than before, and served as the Kublai Khan’s ambassadors.

Marco Polo, aged 17, headed East with his father and uncle, setting out from Venice in 1271 and travelling to and around Asia until 1295. Seventeen of those 24 years were spent in China. Polo later chronicled his travels in Travels of Marco Polo (English title; the Italian title is Il Milione or The Million), which provided Europeans with their first comprehensive look of the Far East.

Geography (finally) reaches Italy

When Marco Polo sailed to China, Ptolemy’s atlas remained unknown in Western Europe. Constantinople was re-captured by the Byzantines in 1261, but in the 14th century it was hit by the Black Plague and a wave of foreign invasions, sending numerous refugees to Italy. Among these refugees were scholars who saved old Greek manuscripts, including Ptolemy’s Geography. In 1405, Geography was translated into Latin and was finally made accessible to Italians.

The map makers of Venice, along with publishers from Florence and Rome, dominated the printed map trade in the 15th and 16th centuries. According to David Woodward in The History of Cartography (University of Chicago Press, 2007): ‘More maps were printed in Italy during that period [1480 to 1570] than in any other country in Europe.’

Map printings were made from woodcuts, where the plates were inked and paper pressed onto the engraving. Copper was later used, but in Venice the woodcut remained king in the 16th century. Woodward argues it might have been because woodcut was used to prepare popular editions of master paintings, and map publishing in Venice began in collaboration with book publishers, who worked in woodcut.

The Jacopo de’Barbari, an impressive woodcut aerial view of Venice produced by artist de’Barbari, was more than a map – it was ‘an advertisement for Venice’s supremacy’ in the art of printing (Crowley, 2015). Hundreds of printmakers’ shops sprouted on the parallel streets of Frezzaria and Merzaria between the Piazza San Marco and the Rialto. By the 1560s, map making was more intense in Venice than in Rome (Woodward, 2007).

One of the greatest Venetian cartographers of this time was Giacomo Gastaldi. Little is known about his life, but his achievements speak for themselves. In 1548, he produced an edition of Ptolemy’s Geography that was noteworthy for two innovations: first, this version now included regional maps of the Americas, the ‘new world’; and two, he and his publisher reduced the size of the volume, creating a compact ‘pocket’ edition of the Ptolemaic atlas. According to Woodward, ‘The senate bestowed on Gastaldi the title of cosmographer to the Republic of Venice in recognition of his extensive contributions to geography.’

Maps as a Status Symbol

Due to the skill and expense required to make them, maps became a status symbol in Venice. By 1565, clients could have maps bound in vellum or leather to make composite atlases. Woodcut or copper plates of maps were valuable enough to be held as collateral.

Rich Venetians even displayed framed maps in the most visible parts of their homes as wall decorations, and to signal their social and professional standing. Crowley shares that the walls of the Doge’s Palace “are embellished with colossal paintings depicting the city’s maritime victories, maps of the oceans and allegorical representations of Neptune offering Venice the wealth of the sea.”

According to Genevieve Carlton (2012) in ‘Making an Impression: The Display of Maps in Sixteenth-Century Venetian Homes‘ published in the International Journal of the History of Cartography, maps in Venice ‘were valued for their ability to construct a public identity for the owner. They were versatile objects that could demonstrate that the owner was a cultured, cosmopolitan man educated about the world, reinforce his professional or trade standing, or enhance a military persona, all to the glorification of the family name.’

Carlton says Venetians saw their maps ‘as consumer objects, which they valued not merely in monetary terms, or even for geographical information, but for the subtle messages they conveyed to their neighbours and visitors.’

Ackroyd says there are many maps of Venice, but Venice, in a sense, is unmappable with the alleys and streets being ‘to labyrinthine, the connections are too circuitous (p.345).’ Travellers say it is better to just explore Venice without a written guide, to stumble upon hidden alleys and to, somewhat ironically, get lost in the city of maps.

If you want to learn more about maps and Venice, please see ‘The Map Unrolls’, a chapter in Peter Ackroyd’s Venice: Pure City, as well as the articles linked here, especially the journal articles by Carlton, Cosgrove, and Woodward, which were used as references to write this post.

You may also want to read our recent article ‘Secret Venice‘ about the powerful Council of Ten, and consider joining a tour of Italy organised by Odyssey Traveller.

Odyssey Traveller’s small group tour in Italy includes a tour of Venice, and is especially designed for senior travellers and examines the heritage, culture, and history of the country, with a stop in Venice to explore places such as Piazza San Marco, St. Mark’s Basilica, and the Doge’s Palace. We go on a city tour with a local guide, exploring the hidden gems and secrets of Venice.

In our time in Venice, we will we will go on a historical walking tour through its beautiful monuments and have our fill of contemporary art as we stroll through amazing museums.

Below is a list of some of our other tours in Italy:

- Heritage, Culture and History of Italy

- Northern Italy Tours

- European Cities Small Group Tour

- Ancient History of Southern Italy and Sicily

The full list can be found here. Happy travelling!

Updated on December 10, 2019

Related Tours

27 days

DecEuropean Cities Small Group History and Cultural Winter Tour

Visiting Albania, Croatia

An escorted tour A Journey that commences in Rome and takes in 12 destinations along its journey to Athens. This is an off season small group journey with like minded people. A small group tour across Southern Europe with local guides sharing authentic in-country authentic experiences for mature couples and solo travellers.

From A$17,295 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Mar, Sep, MayFlorence: Living in a Renaissance City

Visiting Italy

A small group tour with like minded people, couples or solo travellers, that is based in Florence. An authentic experience of living in this Renaissance city The daily itineraries draw on local guides to share their knowledge on this unique European tour. Trips to Vinci, Sienna and San Gimignano are included.

From A$14,375 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Oct, AprTour of Northern Italy's Lakes and Alps

Visiting Italy

A European tour to the stunning Lakes Region of Italy. Your travel experience begins in Milan, daily itineraries include two of the region’s lakes - Garda and Maggiore, plus the Roman villa Desenzona and a day in Cinque Terre. Local guides share experience and knowledge with you on this escorted small group tour for couples and solo travelers.

From A$14,895 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Apr, Aug, MayRenaissance Italy Tour: Story of Five Families

Visiting Italy

Explore Renaissance Italy on this small group tour though an examination of five significant city states. Florence, Urbino, Ferrara, Mantua and Milan were all dominated by families determined to increase the status of their city through art and architecture. Spend time coming to know the men and women who helped create the cities, as well as the magnificent legacy they left behind.

From A$14,295 AUD

View Tour

15 days

DecDiscover Rome | Cultural and History Small Group Tour for Seniors

Visiting Italy

Rome is arguably the most fascinating city in Italy, the capital city, once the centre of a vast, ancient empire and still today a cultural focus within Europe. Explore the city in-depth as part of a small group program spending 15 days exploring, just Rome and Roman History.

From A$9,235 AUD

View Tour

18 days

Aug, SepArt and History of Italy | Small Group Tour for seniors

Visiting Italy

Taken as a whole, Italian Civilization (which includes, of course, the splendid inheritance of Ancient Rome) is absolutely foundational to Western culture. Music, Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Literature, Philosophy, Law and Politics all derive from Italy or were adapted and transformed through the medium of Italy.

From A$16,695 AUD

View Tour