Life in the Medieval British Village: The Definitive Guide

Life in the Medieval British Village In a previous article, we looked at the icons of the British village–the pub and the cottage–and looked at their history and evolution from Roman and Norman times. In…

22 Aug 23 · 15 mins read

Life in the Medieval British Village

In a previous article, we looked at the icons of the British village–the pub and the cottage–and looked at their history and evolution from Roman and Norman times. In this article we will look at daily life in the British village during the medieval period–or the period spanning the 5th century to the beginning of the Renaissance around the 14th century–with a special focus on the manorial system and the homes that people built and lived in.

This article is written as a backgrounder for the Villages of England small group tour offered by Odyssey Traveller. The tour begins with a welcome dinner at a local restaurant, before taking in the beautiful scenery and landscapes of rural England. From our centrally located accommodation, we embark on this unique travel experience through quaint villages and cottages, historic country lanes, and amazing natural landscapes, whilst learning all about their inspiring architecture and fascinating history.

Manorial System

The Middle Ages was a tumultuous period in British history, marked by foreign invasions, the Black Death, and the Hundred Years’ War. Turbulent circumstances push people to look for security, even at the cost of certain liberties, and this was how the manorial system began. The system can be traced to the Roman villa that formed in the midst of infighting and foreign invasions that afflicted the declining Roman Empire in the 5th century.

The villa–either the villa urbana which could be easily reached from Rome or the farmhouse villa rustica in the countryside–was where the Roman elite retired to take a break from urban life. (As Carolyn McDowall [2014] notes, we are not so different from the ancients, with our idealisation of country life.) They were also centres of agricultural production, with labourers and servants attending to the land and the lavish home. However, as the empire declined and “barbarian” raids continued, the Roman landowners felt the need to consolidate their property and their labourers. The poor and the defenceless also found benefit in siding with the landowners. In the new Roman villa system, those with small farms and those with no land at all exchanged their land or their labour in exchange for protection.

When the Franks, a Germanic tribe, invaded the western Roman Empire in the 5th century (the eastern imperial arm would survive as the Byzantine Empire until the 15th century), they also adopted this practice. According to Mark Cartwright (2018) Frankish kings in the 8th century gave parcels of land (benefices) to loyal nobles in exchange for military service, and the nobles then gave the right to the peasantry to work and live on his land in exchange for their service. Thus the manorial system was born in Europe, which in turn supported the feudal hierarchy of lords and vassals.

Manors after the Norman Conquest

The manors, much like the Roman Villa, were the economic and political units of the feudal system that flourished in medieval Europe. The manorial system, or manorialism, existed in Britain under the Anglo-Saxons in some form, but only as an economic arrangement. Land was gifted and purchased, but there was no expectation of service. This changed after the Norman Conquest of 1066.

The Normans were descended from the Vikings who had settled in the area of what would become Normandy (northern France). Shortly after the victory of Duke William of Normandy against the Anglo-Saxon king Harold II at the Battle of Hastings, William–now styled King William the Conqueror–ordered the redistribution of land to his followers, causing the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy to lose its assets. William also commissioned a survey and audit to establish “who held what [land], in the wake of the Norman Conquest itself” and to “clarify what rights and dues were owed to the King”. The 913-page Domesday Book which surveyed England and parts of Wales was released in 1086, and painted a picture of a land now governed by feudal relationships.

According to A. Hamilton Thompson, “manor” comes from the Latin manere–“to remain, to dwell”, and the French word manoir is used to refer to the “chief house in a village”. Thompson says it was a foreign term imported into England, and feudalism a foreign system that had taken hold in the Frankish Carolingian empire, adopted by the Norman duchy, and now imposed on the former territory of the Anglo-Saxons.

“Feudal” comes from the word fief (also source of the word “fee“, or what we pay for a service), says Matthew A. McIntosh. A fief, which may contain one or more manors, was

“a piece of property which a person was given on condition that he (and occasionally she) performed certain services to the one who gave it. A person who received a fief was a vassal of the one who had given him the fief, who was his lord. In the agrarian society of medieval Europe, a fief was usually a specified parcel of land.” (source)

This was similar to the Frankish benefices, and the military service required by the lord depended on the size of the land allotted to the vassal. The larger the land, the more troops (that is, knights) the vassal had to provide if the lord required warriors in battle. If the land was small, then the vassal usually had to fight on the battlefield himself.

In this system of landholding, the King (William) was “at the top of the feudal ladder“, the land parcelled out into smaller and smaller units, from the land given by the King to the tenants-in-chief to the land they gave to their sub-tenants. As McIntosh says, “In feudal society everyone was supposed to have a lord – except the king at the top, who had no lord (at least, not on Earth: he was regarded as God’s vassal).”

The National Archives provides an expanded translation of a Domesday Book entry regarding Earley manor near Reading, showing the detail of record-keeping of William’s men and the web of ownership after the Norman Conquest. (Note: demesne means a portion of the manor not granted to free tenants and held by the lord for his own use. Domesday words were directly translated in bold.)

The King (William) holds in demesne Earley (in lordship – that is, by and for himself; he has not let it out to a sub-tenant). Almar (an Anglo-Saxon) held it in alod (freehold) from King Edward. Then (in 1066, it was assessed for tax purposes) at 5 hides, now (in 1086 it is assessed) for (the equivalent of) 4 hides. (There is) Land for use by 6 ploughs. In demesne (on the lord’s land there is land for) 1 plough and (there are) 6 villans (villagers) and 1 bordar (smallholder) with 3 ploughs. There (are) 2 slaves (owned by the King) and 1 site (or close) in Reading (presumably owned by or part of the manor) and (there are) 2 fisheries worth(rendering) 7s and 6d (per year) and 20 acres of meadow. (There is) Woodland for (feeding) 70 pigs. At the time of King Edward (1066) it was worth 100s, and afterwards (when William acquired the manor) and now(1086) it is worth 50s. (Source.)

Thompson notes that in popular use, the manor was treated as if it were a parish, that is, “a fixed geographical area with definite boundaries”, but in reality manors belonging to one lord could be scattered across the land, and different lords may have holding rights in a single township, “cross[ing] and recross[ing] each other in a most perplexing way.”

In general, a manor would have the manor house, the principal dwelling in the village inhabited by the lord (or a steward, if the lord had more than one manor and was living elsewhere) with fortified walls and sometimes a moat, according to Mary-Ann Ochota in Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape (Frances Lincoln, 2016, p. 194), though the moat was usually there more for status than actual defence. The manor house was often built next to a church and a mill.

In the village would be a cluster of huts and cottages, barns and gardens, surrounded by arable land and pastures. The Earley manor described above even had fisheries and woodland. The lord of the manor would have his own plot of land (demesne) and might rent other parts to free tenants, who were “often enterprising smallholders, renting land from the lord, or even owning land in their own right” (Alixe Bovey, 2015). Rent was typically paid in the form of produce.

The rest of the land (including the lord’s demesne) would be farmed by landless tenants called serfs, who were bound to the manor on “unfree tenure”. This meant they couldn’t just quit work on the manor without the lord’s permission, and could be arrested and punished if they did.

The word “peasant” referred to both the free tenants and serfs, but in contemporary use it usually only referred to the latter. As we’ve mentioned before, “peasant” more accurately referred to a person who lived off of the products of his or her own labour, not necessarily someone who lived in extreme poverty. But serfs did make up a large majority of the medieval population. According to Bovey, “some 85 percent of the population could be described as peasants. Peasants worked the land to yield food, fuel, wool and other resources…[Serfs] were obliged both to grow their own food and to labour for the landowner.”

Unfree tenure was also inherited, passing from parent to child. Unlike slaves, however, serfs were not considered the personal property of the lord and could not be bought and sold (unless the lord was selling the rights to a serf’s labour or service).

Manors were largely economically, and even politically, self-sufficient. They were beholden to the Crown, but they also had their own manor courts run by the lord or steward. (More serious crimes like murder had to be tried at the Crown court, however.) Villagers followed the agrarian calendar and grew their own food.

Medieval Homes

In some British villages, people lived in longhouses (or blackhouses, as they were called in Scotland), designed to house both people and animals under one roof to protect precious livestock from the elements and from theft (Ochota, 2016, p. 225). People and animals would use the same front door but the side of the house occupied by animals would be on a lower floor elevation. This tradition dated back to Anglo-Saxon times.

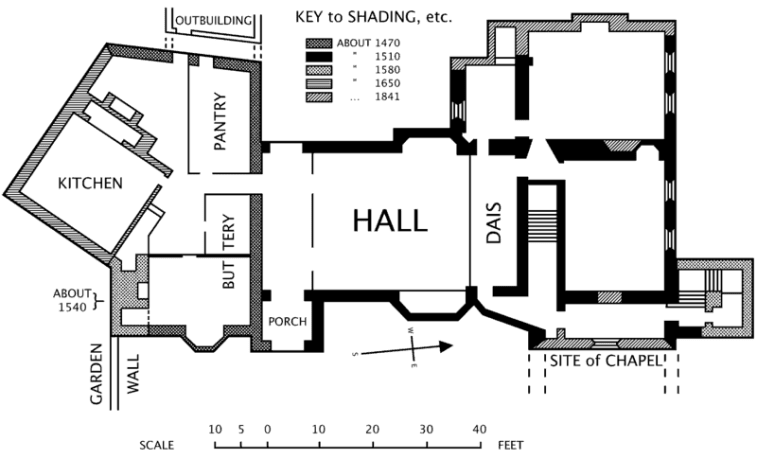

The hall house was the more common “model” during the late Middle Ages, gaining popularity from the 14th to the 16th centuries (p. 226). According to Bill Bryson in At Home: A Short History of Private Life (Doubleday, 2010), “the hall effectively was the house” (p. 53, emphasis his). Life revolved around this large chamber which had an open, central hearth, the smoke rising to the rafters, escaping through the thatched roof, and depositing soot on the exposed timbers.

The family led by the head of the household ate on a raised platform called a dais, a tradition still seen in the dining halls of some colleges and boarding schools (p. 54). The head of the household was called the “husband”, from the Old Norse word meaning “master of the house,” literally “house-dweller”, also the root of “husbandry” or the practice of land management (p. 54). The word only assumed the contemporary definition (married male partner) in the late 13th century, replacing the Old English word wer as companion for the word “wife”.

Food was cooked on the central hearth, or if the household was wealthier, in a separate kitchen at the back, with food stored in the pantry (for dry foods) and the buttery (for liquids, such as ale). Proper food storage was important in order to survive the long, winter months.

Other interior spaces separate from the all-important hall were a side chamber (or chambers) called the parlour, where the master of the house could hold private meetings; and an upper chamber called the solar (from French solive, “beam”), reached by a ladder (p. 54). Sleeping arrangements were informal; the term “make a bed” survives, says Bryson, because in the Middle Ages “that is essentially what you did” (p.59), using cloth or a heap of straw.

The late Middle Ages saw the “growth of specialised trades, such as thatching, carpentry, daubing, and the like” (p. 63) which showed that people were paying attention to building good homes. We have more information about building British cottages in our previous article.

Barns

There wouldn’t be room in the hall for livestock, so in medieval times animals–usually milk cows and oxens–were kept in combination barns which also stored fodder, grain, and tools. Combination barns found in the midlands, East Anglia, and southern England date from the Middle Ages. In later years, livestock would be moved to detached buildings, and the barn used mainly for corn storage and processing.

Barns featured divisions called “bays“, and had a storage bay and a threshing bay. “Threshing” means beating crop on the floor to separate grain from the husks, called chaff. The chaff was then stored and used as animal feed.

Some villages also had bastles, or fortified farmhouses, though these structures usually date from the 16th century.

Under the manorial system, peasants were expected, in addition to paying the lord in produce, to give tithe to the Church as support for the local priest (Ochota, 2016, p. 233). A tithe means “a tenth part” so what was due the clergy would be a tenth of the household’s income or harvest. The produce was then stored in a tithe barn (p. 233).

Dangers in the Medieval Village

The medieval village could be highly dangerous, with violence prevalent in various forms. Medieval records demonstrate high incidents of rape, assault, domestic violence, and homicide. Homicide was especially widespread, with historians calculating its levels in England were at least 10 times days what they are today. Often the murders were unpremeditated, but sometimes longstanding, multi-generational family feuds lay behind them. Bloodshed also resulted from local or regional disputes over land, money, or other issues.

Social urban unrest was also quite common due to the high levels of structural inequality caused by rapid commercialisation and urbanisation. This in turn often led to violent riots and uprisings. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 in England is perhaps the most famous. It was sparked by the imposition of the unpopular poll tax of 1380, in the wider context of economic discontent (a result of heavy taxation and labour shortages due to the Black Death). After spreading across England, the revolt ultimately contributed to changes in labour relations and land tenure systems in the country.

The Black Death, as we talked about in a previous article, itself was another major danger in the medieval village. Caused by the bacterium called Yersina pestis, the plague arrived in Britain in the mid-14th century, carried by fleas on rats. The disease, which peaked between 1347 to 1352, had a devastating impact in Britain due to its high mortality rate, killing around 30-50% of the population.

Many medieval villagers also perished due to famine. Often many would starve when food supplies dwindled due to bad weather or poor harvests. Others barely survived on meagre rations like berries, bark, and mildew-damaged corn and what. Eating little, however, they suffered malnutrition, making them very vulnerable to disease. Deadly epidemics like tuberculosis, dysentery, influenza, mumps, and typhoid often followed famine.

Life for children, in particular, was dangerous in the Middle Ages, with incredibly high mortality rates. Surviving written records have led to estimates that 20-30 per cent of children under seven died, although the actual figure is very likely higher. Malnutrition and various disease and infections were the biggest killers, with infants and children under seven particularly vulnerable. Often accidents also involved children, who were usually left unsupervised day and night due to parents’ busy agricultural work. Coroner’s rolls report, for example, of children falling into ditches full of drain water and drowning; trampled by beasts when accidently entering into fields; and burned by fires in family hearths.

The Role of the Church

The Church was a powerful institutional in the Middle Ages, playing a dominant role in people’s lives. Pretty much all people believed in God and the concepts of heaven and hell and upheld Christian values and morals. Everyone, therefore, was expected to go to church, which in turn gave the institution great power and influence over people.

The spread of the Church started in the late Anglo-Saxon period, as small churches began to be built to serve smaller areas. This process then picked up after the Norman conquest, with William I rapidly building churches and monasteries. Building was often driven by local lords who would pocket a portion of the tithe people had to pay to support the church. A tithe was a 10 per cent tax on what people earned annually, payabale to the Church in either money or in goods produced by the peasant farmer. In addition to collecting tithes, the Church was also responsible for the vital duties of treating the sick and providing education.

On Sunday the Church was the social hub of the village. People of the community would meet at their church to hear news and share stories. After worships, social gatherings of all kinds would take place, which could often get rowdy due to the high consumption of ale. The Church’s calendar also provided the basis for religious holidays, and parishes observed several feast days providing a rest from labour throughout the year. All meant there was a lot of celebrating going on. The Church’s rituals also marked key moments in people’s lives, with churches the sites for baptisms, funerals, and weddings amongst other events.

Decline of the Manorial System

The decline of the manorial system, a system that thrived in a decentralised, local economy, was caused by several factors: the Black Death, the increased use of coinage, and the rise of cities.

In the late Middle Ages, coinage began to replace barter during trade in Europe with the debasement of money. Debasement meant adding other (less precious) metals to silver or gold coins. This meant more coins could be produced, carried (gold coins can be quite heavy), and used. Cities also created a market for agricultural surplus as well as luxuries from other countries that could be purchased. In order to create more wealth in coins, lords began accepting money payment from free tenants, and from serfs who would rather pay than labour on the field, eventually allowing serfs to buy their way to freedom. People also began to pay money in exchange for services (wages), especially to skilled tradesmen.

The Black Death, meanwhile, decimated the agricultural labour pool. As labour supply was low, surviving workers could demand (and indeed demanded and received) higher nominal wages as well as better working conditions.

The manorial system began to decline in the face of all these changes, giving rise to a new system entirely based on money: the tenant paid money to the landlord for use of his land, and the landlord paid money to labourers. Serfs were no longer tied to their lord and to manorial land, and could now be paid coin for their services.

A form of agricultural tenancy survived in the English countryside well into the 19th century, and renting out land was still practised by the aristocracy to this day. As we’ve written before, a third of Britain’s land still belongs to the aristocracy. Those who owned land in London and other city centres grew even wealthier from rental income. The price of land in the country fell as city housing prices skyrocketed, and aristocratic landowners took advantage by becoming landlords, building houses and flats and selling them on a leasehold basis. This meant, according to Christ Bryant in The Guardian, that the “owners” of these homes pay ground rent to the aristocrats “to whom the property reverts when their leases (which in some areas of central London are for no more than 35 years) run out.” The Duke of Westminster, for example, owns parts of Mayfair and Belgravia in London, and Earl Cadogan owns parts of Cadogan Square, Sloane Street and the Kings Road, locations that command high rental values. You can read more about it here.

The changing times also made changes to the medieval home. The introduction of the chimney (the word “chimney” was first used in the early 14th century [Bryson, 2010, p. 63]) ended the tradition of having an open hearth in the middle of the house, and allowed people to build a second storey and divide the hall house into more private spaces. This caused the hall to diminish in size and importance, until it simply became an entrance. “Manor house” is still used in England to refer to large country mansions that may or may not have a manorial history.

If you want to learn more, we recommend Bill Bryson’s At Home: A Short History of Private Life (Doubleday, 2010) and Mary-Ann Ochota’s Hidden Histories: A Spotter’s Guide to the British Landscape (Francis Lincoln, 2016), as well as many online resources linked throughout this piece.

You may also consider joining one of Odyssey Traveller’s many tours to the British Isles, such as the Villages of England tour we’ve mentioned earlier. The 19-day fully escorted tour will let you explore from our well-appointed hotel the history and culture of the British countryside. This tour takes us to the stone circles and henge monument at Avebury, the famous Lake District, the white-washed, thatched-roofed cottages of Milton Abbas, the traditional village buildings of Sussex, the rolling hills of Dartmoor, England’s most photographed bridge in Ashford-in-the-Water, and the delightful coastal village of Port Isaac. We stroll through the villages on Cornwall’s coast, and view the castle towering over the cobblestoned main street of Dunster. All of this will offer a panoramic and revealing portrait of England’s villages.

Another tour that may be of interest is the Prehistoric Britain tour, which visits Skara Brae and other historic sites in Orkney, Shetland, and Wales.

Be inspired by our memorable tours on offer. For more information on all of our tours to the British Isles, click here.

Originally published May 18, 2019.

Updated on October 9, 2019; August 22, 2023.

Articles about Britain published by Odyssey Traveller:

- The London Underground

- Victorian Women’s Fashion

- Queen Victoria’s Britain, Part 1 and Part 2

- Understanding British Churches

- Georgian Architecture

- London’s Victorian Architecture

- England’s Cathedrals

External articles to assist you on your visit to Britain:

- National Parks UK

- William the Conqueror (History.com)

- Queen Victoria

- The Royal Parks of London

- The Royal Mausoleum

Related Tours

19 days

Jun, SepEngland’s villages small group history tours for mature travellers

Visiting England

Guided tour of the villages of England. The tour leader manages local guides to share their knowledge to give an authentic experience across England. This trip includes the UNESCO World heritage site of Avebury as well as villages in Cornwall, Devon, Dartmoor the border of Wales and the Cotswolds.

From A$16,995 AUD

View Tour

21 days

AugPrehistoric Britain small group history tour including standing stones

Visiting England, Scotland

This guided tour invites you to explore UNESCO World heritage sites at Skara Brae in the Orkneys, Isle of Skye, and Stonehenge in a prehistoric tour. This escorted tour has trips to key sites in Scotland, and the Irish sea in Wales such as Gower Peninsula and National Museum in Cardiff and England. Each day tour is supported by local guides.

From A$16,750 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Apr, SepSmall group tours Medieval England

Visiting England

A small group tour of England focused on Medieval England and Wales. Spend 21 days on this escorted tour with tour director and local guides travelling from Canterbury to Cambridge, passing through Winchester, Salisbury, Bristol, Hereford and Norwich along the way. Castles, villages, Cathedrals and churches all feature in the Medieval landscapes visited.

From A$14,665 AUD

View Tour

23 days

AprAgrarian and Industrial Britain | Small Group Tour for Mature Travellers

Visiting England, Wales

A small group tour of England that will explore the history of Agrarian and Industrial period. An escorted tour with a tour director and knowledgeable local guides take you on a 22 day trip to key places such as London, Bristol, Oxford & York, where the history was made.

From A$17,275 AUD

View Tour

16 days

JunBritish Gardens Small Group Tour including Chatsworth RHS show

Visiting England, Scotland

From A$16,895 AUD

View Tour

22 days

Apr, AugSeven Ages of Britain, snapshots of Britain through the ages.

Visiting England, Scotland

This guided small group tour starts in Scotland and finishes in England. On Orkney we have a day tour to the UNESCO World heritage site, Skara Brae, before travelling to city of York. Your tour leader continues to share the history from the Neolithic to the Victorian era. The tour concludes in the capital city, London.

From A$15,995 AUD

View Tour