Ten Personalities from Queen Victoria's Britain (Part 1 of 2)

Article for senior couples and mature solo travellers exploring Queen Victoria's Empire including Britain and the personalities. Supports small group educational tour about the monarch and the industrial revolution.

30 Oct 21 · 17 mins read

Ten key influencers that shaped Queen Victoria’s Britain (Part 1 of 2)

This article related to Queen Victoria’s Britain was prepared by one of our Odyssey Program Leaders, Mal Bock. You may also want to read the previous article providing an overview of British life during Queen Victoria’s time. (Part 1 | Part 2).

Queen Victoria and her family constitute just a fraction of the people we’ll meet during our exploration of Victoria’s Britain. Most of the people who made their mark were men and most were from the middle class and above. We will, however, find a couple of important women and a few people who rose through society with the help of ability and good fortune. This article lists 10 key influencers that shaped Great Britain in this period.

1. Sir Charles Barry (Houses of Parliament architect, 1795-1860)

Charles Barry was born into the comfortable middle class but his father died when he was young and he had to leave school at fifteen after what he called “an imperfect education”. After leaving school he was articled to a surveying firm where he stayed for the next six years, working industriously but finding time to paint, exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

In 1817, when he came into a small inheritance left by his father, he set out to travel through Europe and the Middle East, painting and sketching buildings as he went. He travelled through France, Italy, Greece and Turkey before taking employment with a gentleman who took him to Egypt and Palestine, employed to sketch as he went.

When he finally returned to England in 1820, Barry set himself up as an architect, taking on a number of prestigious assignments including the Manchester Institute of Fine Art. Although he initially preferred to work in an Italianate style, Barry was a practical man and was prepared to design in Gothic Revival when necessary. When a competition was announced, in 1835, for the design of the Houses of Parliament in either Elizabethan or Gothic style, Barry rose to the occasion. Barry, having asked Augustus Pugin to draw up plans for the interior, was awarded the contract and worked on the project until his death in 1860. He was buried in Westminster Abbey.

2. Augustus Welby Pugin (Gothic Revival Architect, 1812-1852)

Augustus Pugin lived a short life but an extremely influential one. He was the son of a French father and an English mother. His father was a draughtsman and architect and the young Augustus worked with his father from an early age.

Pugin was appalled by the indifference of the modern city. He came to believe that many of the ills of early 19th century society could be connected to its poor architecture. His father had published books on Gothic architecture and Augustus began to equate the solidity of the Gothic with Christian virtue. In 1843 Pugin converted to Roman Catholicism and the next year Charles Barry asked him to design plans for the interior of the new Westminster Palace.

In 1836 he had published his architectural manifesto, Contrasts, which linked the character and quality of society with the calibre of its architecture. Pugin had examined modern architecture and found it wanting. He stressed the need for a Gothic Revival believing that the current decline in spirituality could be linked to shoddy architecture. In 1841 he published another influential work, True Principles of Christian Architecture, which also equated Christian architecture with a Gothic revival. The eminent Victorian critic, John Ruskin, used this work as a foundation for much of his criticism.

Pugin’s business took off. By the time he was 30 he had designed 22 churches, 3 cathedrals, 3 convents, half a dozen houses and a Cistercian Monastery. Probably the most famous of his churches is the one at Cheadle in Staffordshire. During his short life Pugin also found time to marry three times (the first time when he was only nineteen) and to produce seven children.

In February 1852 Charles Barry visited Pugin in his home and asked him to design a bell tower for Westminster Palace. Pugin worked on the design for what we now call the Big Ben tower until he had completed it and declared, “It is beautiful”. A few weeks later he took ill, suffering a complete mental and physical breakdown. For a short period he was confined to the Bethlehem Asylum (Bedlam) until declared fit enough to return home under the care of his wife. He died in September 1852.

3. Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

Florence Nightingale was born to a wealthy, well-connected English couple in the city of Florence while they were on an extended honeymoon. Well educated by her father, Florence was unhappy with the restricted life expected of young women of the upper classes. She wanted to do more with her life than just marry, as was expected by her parents and society. Florence claimed that she had been called by God to be a nurse.

Although her parents were considered liberal-humanists, nursing was not what they had in mind for their attractive young daughter and the family was torn apart by dissension. Florence persevered and was eventually allowed to undertake training in Germany and to work two hospitals back in England.

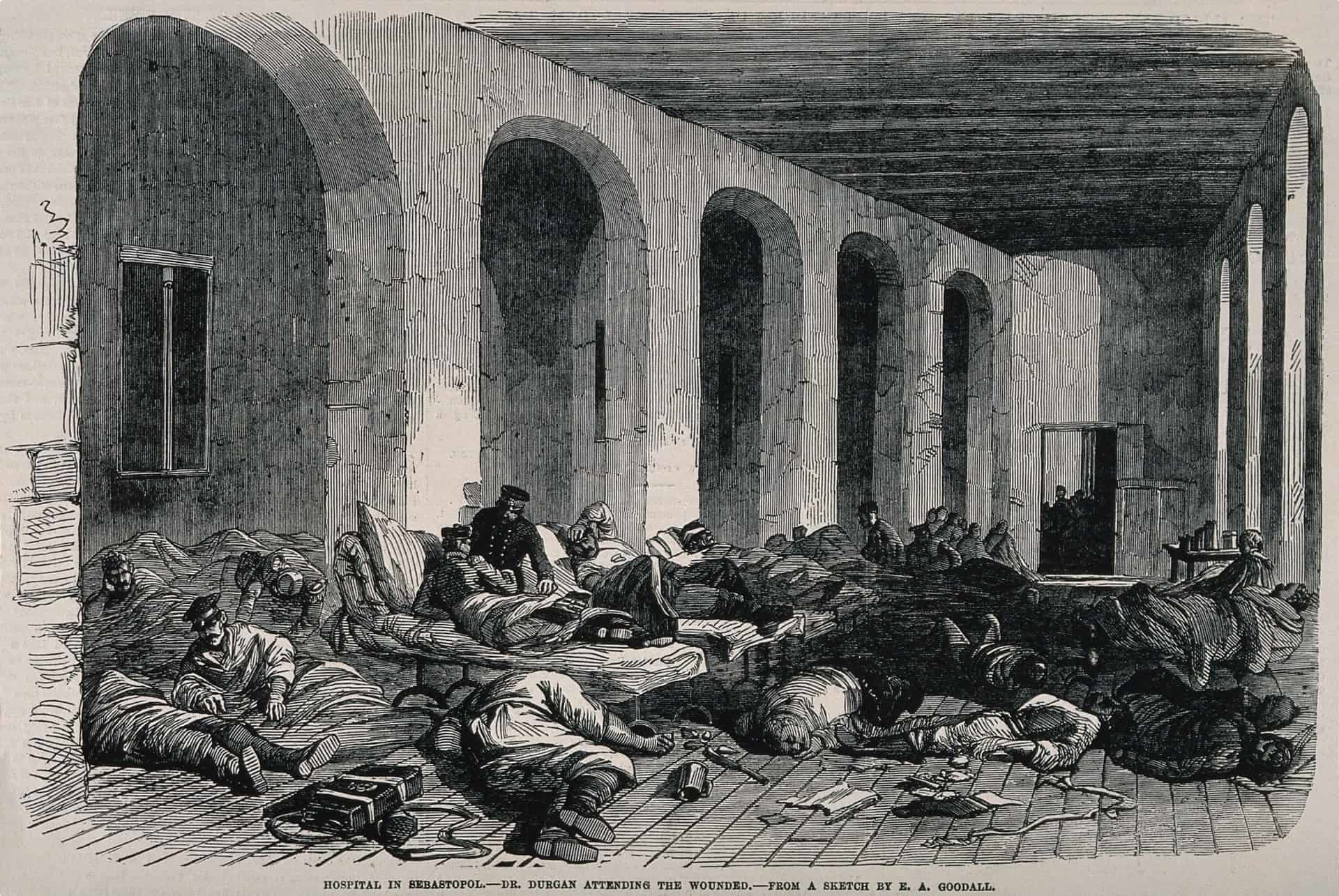

In 1853 the Crimean War broke out and dispatches from the front emphasised the terrible conditions sick and wounded soldiers were facing. This was the chance Nightingale had been waiting for. She persuaded a close friend, Sidney Herbert, Secretary for War, to send her to the Crimea with a contingent of female nurses. Once there she attempted to bring order into the chaotic conditions, emphasising personal hygiene among the patients and trying to provide rations and medical supplies.

Unfortunately, even in her hospital at Scutari, more soldiers died of disease than battle wounds. Nobody at the time knew anything about germs and Nightingale, like everybody else, believed that diseases were carried by miasmas (bad smells). She insisted that the soldiers in her care were washed but nothing was done about the fact that the hospital was situated on top of a cess pit. Raw sewage was coming up through the floors and ventilation was poor. It was only once a team of sanitation experts arrived and flushed out the sewers and improved ventilation, that the death rate began to drop.

On her return from the Crimea, Nightingale was welcomed as a heroine. The Nightingale Fund was established for the training of nurses at St Thomas’ Hospital. Nightingale, although in poor health, spent the rest of her long life promoting reform and organising the nursing profession.

4. Charles Dickens 1812-1870

“He was a sympathiser to the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England’s greatest writers is lost to the world.”

Inscription on the tomb of Charles Dickens, possibly Victorian England’s greatest novelist

Charles Dickens was enormously popular during his lifetime and is still one of Britain’s best known novelists. Many characters from his sixteen completed novels have passed into the consciousness of people living almost 150 years after his death. Who hasn’t heard of Oliver Twist, Miss Havisham or Scrooge? His novels, written to be serialised in the popular press, have proven to be easily adapted to stage and screen.

Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth, the second of eight children. His father was an improvident clerk in the Navy Pay Office, often falling into debt. The early years of his childhood were relatively comfortable though he later complained that he had been largely ignored by his parents. During these early years he read voraciously, particularly from adventure stories such as Robinson Crusoe. His childhood ended abruptly at the age of twelve when his parents and his younger brothers and sisters all ended up in the Marshalsea, a debtor’s prison.

Young Charles was forced to leave school and go to work in a boot blacking warehouse, putting labels on bottles of boot black. The grim conditions of his employment left Dickens with the background for many of his later novels. Eventually, on receiving a legacy, Charles’ parents were released from prison and Charles returned home. He later claimed that his mother had been prepared to leave him where he was working and some critics claim that this apparent neglect permanently soured his relationship with women. He returned to school but left again aged fifteen and went to work as an office boy and then as a reporter.

In 1832 he began to contribute a series of impressions to magazines under the pseudonym of Boz. These were published in book form in 1836. The success of this book encouraged him to marry Catherine Hogarth with whom he was to have ten children before the couple became estranged. In 1865, returning from a visit to Paris with his young mistress, Ellen Ternan, and her mother, Dickens was involved in a serious train accident. He was able to give assistance to injured passengers while keeping Ellen and her mother out of the public gaze.

During his long career Dickens was to write short stories and essays as well as his sixteen published novels. He went on numerous lecture tours (including long tours to the United States) and performed public readings of his works. His novels, published first in serial form in newspapers, offered a fierce criticism of the social stratification of Victorian society and brought the plight of the poor to the attention of his vast reading public. He suffered a stroke in 1870 and died five days later, leaving his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, unfinished.

5. Sir John Soane (architect, 1753-1837)

John Soane died the year that Victoria came to the throne but left behind an eccentric museum that is well worth visiting. Sources differ on exactly where he was born but most agree that he was the son of a mason or bricklayer and that he was orphaned as a teenager. His rise to fame and fortune was a combination of talent and good luck.

At the age of 15 he was employed as an errand boy in the firm of George Dance Jr., surveyor to the City of London. Here his talent for drawing was recognised and he was transferred into the office and began to study architecture at the Royal Academy. He transferred to the firm of Henry Holland and continued to study, earning a silver medal at the RA in 1772 and a gold medal in 1776. Along with the gold medal came a scholarship to study abroad.

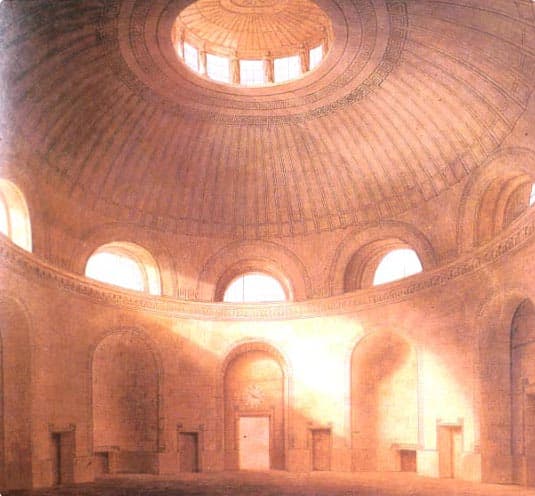

Soane spent the next three years on the continent, chiefly in Italy, concentrating on a study of antiquities. It was during this time that he probably developed his own brand of neoclassicism (just the sort of style detested by Pugin). It was in Italy that he met, and travelled with, a number of influential and wealthy English aristocrats who were to prove very useful to him back in England. He returned to England in 1870 and set up in practice designing many country houses and making a wealthy marriage. His business really took off when he was appointed architect to the Bank of England, probably his best known building.

John Soane and his wife Elizabeth had a long and happy marriage but they were less fortunate with their children. Two of their four sons died as infants and the other two turned out badly. John, the elder boy was lazy and suffered from ill health. He died at the age of 36 leaving debts and a young family which Soane supported. George was also lazy and had an uncontrollable temper. On his marriage, George wrote to his mother saying, “I have married Agnes to spite you and father.” Shortly before his mother’s death George anonymously published defamatory articles about his father, went into debt, was sent briefly to debtors’ prison and later entered into a menage a trois with his wife and her sister, both of whom he physically abused. It is no wonder Soane cut George out of his will.

In 1806 John Soane was appointed Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy and in 1831 he was knighted. Although now very famous, his work often received criticism for his profusion of ornamentation. What Sir John Soane is best remembered for now, however, is his wonderfully eccentric museum in Lincoln’s Inn Field. Sir John spent many years towards the end of his life collecting for a display in his house and in the specially built gallery next door. His collection included an alabaster sarcophagus from Egypt, Hogarth’s “The Rake’s Progress”, illuminated manuscripts, rare books, gems and plaster casts, all crowded together in the space of two houses. On his death he left the museum and the collection to the nation but very little to his son George.

6. Sir Frederick Leighton (painter and sculptor, 1830-1896)

Frederic Leighton was born into a wealthy, well connected, upper middle class family. His father was a doctor and his grandfather had been physician to the Russian royal family. Nominally enrolled at the London University College School, he spent most of his childhood travelling on the continent with his parents. He was to grow up to become one of the most celebrated of all Victorian artists.

When Frederic was 16 the family moved to Germany where he began his artistic training. For the next 14 years he lived mainly in Germany, France and Italy where he met many leading artists, studied and painted. He returned briefly to England in 1855 when he exhibited his first major work, Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is Carried in Procession through the Streets of Florence. The painting was bought on the day the exhibition opened by Queen Victoria who wrote in her diary:

“There was a very big picture by a man called Leighton. It is a very bright and very beautiful painting … so bright and full of light. Albert was enchanted with it – so much that he made me buy it.”

In 1860 Leighton moved back to Britain and became associated with the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. By the age of 30 he was one of the best connected and charismatic members of the European art world but it was some years before he was accepted by the Royal Academy as a member. In 1864, however, he was accepted in the RA, eventually becoming its president.

Frederic Leighton was one of the most brilliant and influential artists of his era but now his name has been mostly forgotten by the general public. This was not the case in his own time. In 1878 he was knighted by the queen at Windsor and in 1896 he became the first painter to be given a peerage. Unfortunately Baron Leighton did not live long to enjoy the honour. He died on the 24th of January, 1896, just one day after the peerage was issued.

7. Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, in 1809, the fifth of six children of wealthy society doctor and financier Robert Darwin and Susannah Darwin (née Wedgwood, a daughter of the founder of the famous Wedgwood porcelain company). His family were non-conformist Christians and both his grandfathers, Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood, were prominent abolitionists. Darwin studied medicine and arts at Edinburgh and Cambridge University, but neglected these studies to pursue his interest in natural history and geology.

Darwin took part, as a naturalist, in a five-year geological survey voyage around the world on the HMS Beagle from 1831 to 1836. He visited South America, the Pacific Islands, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa, noting the variations and similarities of life in each of these places. On this journey Darwin observed and collected specimens of birds, animals, plants and fossils in many different countries, which would eventually form the basis of his theories of evolution and natural selection. His collections and papers on his observations made Darwin a celebrity in scientific circles and provided much material for other naturalists to study for years to come.

In 1859 Darwin published his book On the Origin of Species (or more completely, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life), a book which changed scientific opinion on the theory of evolution. This book was followed by a second, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) which more explicitly discussed evolution in relation to humans. The books revolutionised scientific thinking about evolution, though they sparked a religious debate on the origin of humans.

Darwin suffered from ill-health during much of his adult life, but managed to continue working and produced new ideas throughout his life. He also fathered ten children, seven of whom survived into adulthood. He spent most of his life in Shrewsbury, London and Downe, in Kent, where he died in 1882, aged 73.

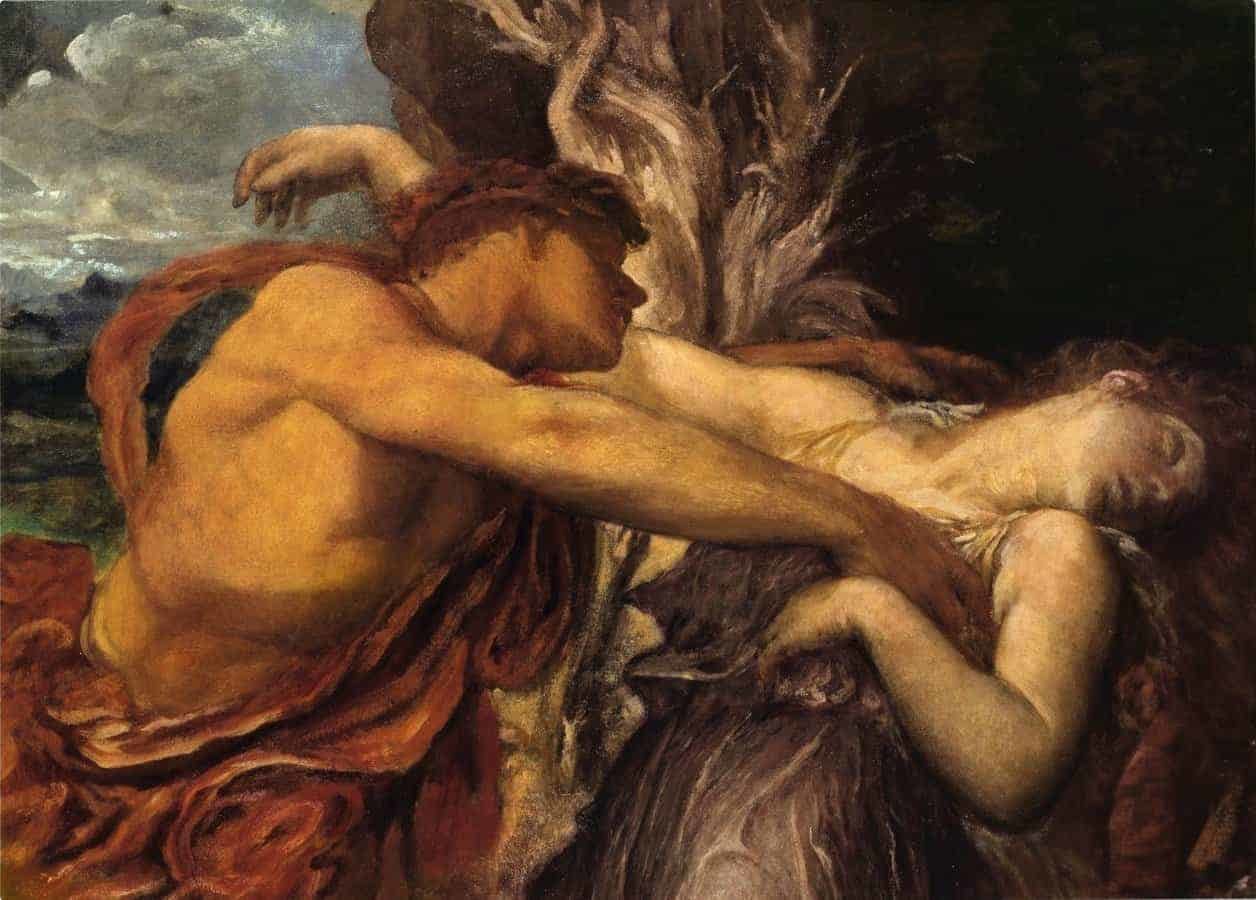

8. George Frederic Watts (Artist, 1817-1904)

“I paint ideas, not things”

George Frederic Watts was the son of a piano maker and tuner. Watts was a sickly child, unable to attend regular school, so he was educated at home by his father. His education concentrated on strict Christian values with the addition of Greek mythology. He came to resent the Sabbatarian restrictions but to value the Greek mythology. His artistic talents emerged early and at the age of 10 he entered the studio of the sculptor, William Behn, which allowed him access to the British Museum and the Elgin Marbles. He later claimed, “The Elgin Marbles taught me everything. It was from them alone that I learned.”

At 18 Watts joined the Royal Academy but seldom attended lectures, finding them uninspiring. By this time he was already painting portraits and had acquired a number of wealthy patrons including Alexander Constantine Ionides. In 1843 he won a competition for the design of a mural for the new Palace of Westminster and used the prize money to fund an extensive tour to Europe. He remained away for the next three years. An extended period in Italy fostered his love of Italian Renaissance painters and their work.

Upon his return to England in 1847, Watts turned increasingly towards social realism in his art, attempting to draw attention to the living conditions of the working class. He was increasingly distressed by the poverty seen in London and in Ireland, where disease and the potato famine were having a devastating impact on the population. He was influenced by the writer, Thomas Carlyle, who believed that art should be “both spiritual and intellectual”. It was during this period that he became friends with other leading artists and writers including Sir Frederic Leighton, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Makepeace Thackery and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. As his paintings became more powerful and renowned, he twice refused a baronetcy from Queen Victoria and attempted to stay out of the public gaze.

He certainly entered the public gaze in 1864 when he met the young actress Ellen Terry. He was enthralled by her beauty and she became his muse. They were married when she was 16 and he 46, though they separated after only 10 months. It was to be another 20 years before he married again. This time, although she was only 36 to his 69, it was a much more equitable match. Watts’ new wife was Mary Frazer-Tytler, a Scottish potter and pioneering suffragist with an established reputation and many similar reformist ideas to his own.

In 1891 the couple moved to Compton, near Guildford in Surrey, having commissioned an Arts and Crafts house to be built for them. They later added a purpose built gallery. Mary set up a pottery training school for local people and later still, a working pottery. Both Mary and George Frederic believed that art should communicate something worthy. It should uplift the soul. Their work reflected their social conscience and progressive socio-political positions.

In his lifetime Watts was hailed as the “greatest painter since the Old Masters” and as “The English Michelangelo”. When he died in 1904 The Times claimed, “The most honoured and beloved of English artists is dead.” In 1904 he was one of the most famous artists in the world having exhibited widely in the US as well as Britain. Today, like Sir Frederic Leighton, he is largely forgotten.

9. Evelyn de Morgan (Pioneering Victorian Female Artist, 1855-1919)

Mary Evelyn Pickering was born into a wealthy family and educated at home in the accomplishments typical for girls of her class in the classics, music and art. Her talents were recognised by an artist uncle, John Rhoddam Spencer Stanhope, who encouraged her to pursue this interest. Despite initial opposition from her parents she was eventually allowed to enrol at the South Kensington National Art Training School before becoming the first female to be admitted, in 1873, to the Slade. She exhibited regularly between 1877 and her death in 1919.

In 1883 she met her future husband, ceramicist William de Morgan, and they were married in 1887. Unlike many women of the period, Evelyn continued with her work. She painted strong, athletic women and used a rich colour palette which catches and holds the viewers’ attention. She and her husband developed a different way of using paint, mixing it with glycerine to produce both clarity and colour.

An interest in the spiritual world was common in the Victorian world. William De Morgan’s mother was a clairvoyant medium who encouraged both Evelyn and William to develop an interest in spiritualism. They experimented with automatic, spirit writing, in an attempt to commune with the inmates of the other world. This interest can be seen in some of Evelyn’s work and the idea of spiritual progress towards the afterlife, and the struggle for enlightenment are recurrent themes in her paintings.

Because of her husband’s ill health the couple spent long periods of each year in Florence where her uncle lived. The couple rented an apartment there and frequently stayed for the winter months. Here she was strongly influenced by the paintings of Botticelli and a number of her paintings were clearly inspired by works she saw in the Uffizi. Back in England her style evolved to reflect the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s interest in medieval subjects. Her work also often reflected her political ideas and her frustration with the limitations placed on women during the Victorian period. This can be seen particularly in paintings such as The Gilded Cage and The Prisoner. In 1889 she and her husband were both signatories of the Declaration of Women’s Suffrage.

10. Isambard Kingdom Brunel (Engineer, 1806-1859)

According to his BBC biography, “Brunel was one of the most versatile and audacious engineers of the 19th century, responsible for the design of tunnels, bridges, railway lines and ships.”

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born on 9 April 1806 in Portsmouth. His father Mark was a French engineer, with Royalist sympathies, who had fled France during the revolution, and his mother was an English girl who was working in France when the revolution began. They first met in France and were reunited in England where they married and had three children. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, their third child and only son, was educated both in England and in France, receiving the very best education that his father could afford.

When he returned to England he went to work for his father. Brunel’s first notable achievement was the part he played with his father in planning and then building, the Thames Tunnel from Rotherhithe to Wapping, completed in 1843. This project was both difficult and dangerous. Several accidents took place and in 1828 two senior men were killed in one accident. Isambard was also seriously injured in this accident and forced to spend many months recuperating.

In 1831, after much opposition from renowned engineer, Thomas Telford, Brunel’s designs finally won the competition for the Clifton Suspension Bridge across the River Avon. Construction began the same year but it was not completed until 1864. The project was dogged with financial and political difficulties and was not completed until five years after Brunel’s death, to a design based on those he had submitted thirty years previously.

The work for which Brunel is probably best remembered is his construction of a network of tunnels, bridges and viaducts for the Great Western Railway. In 1833, he was appointed their chief engineer and work began on the line that linked London to Bristol. Impressive achievements during its construction included the viaducts at Hanwell and Chippenham, the Maidenhead Bridge, the Box Tunnel and Bristol Temple Meads Station.

Brunel is noted for introducing the broad gauge in place of the standard gauge on this line, though this was later abandoned. While working on the line from Swindon to Gloucester and South Wales, he devised the combination of tubular, suspension and truss bridge to cross the Wye at Chepstow. This design was further improved in his famous bridge over the Tamar at Saltash near Plymouth.

As well as bridges, tunnels and railways, Brunel was responsible for the design of several famous ships. The ‘Great Western’, launched in 1837, was the first steamship to engage in transatlantic service. The ‘Great Britain’, launched in 1843, was the world’s first iron-hulled, screw propeller-driven, steam-powered passenger liner. The ‘Great Eastern’, launched in 1859, was designed in cooperation with John Scott Russell, and was by far the biggest ship ever built up to that time, but was not commercially successful.

Brunel was also responsible for the redesign and construction of many of Britain’s major docks, including Bristol, Cardiff and Milford Haven.

Brunel died of a stroke on 15 September 1859.

Click here for Part 2, where we get to know more famous personalities from Victorian Britain.

If you want to learn more about Queen Victoria’s Britain, click through to sign up for our tour.

We also have several other tours exploring the sights and history of the British Isles.

About Odyssey Traveller

Odyssey Traveller is committed to charitable activities that support the environment and cultural development of Australian and New Zealand communities. We specialise in educational small group tours for seniors, typically groups between six to fifteen people from Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada and Britain. Odyssey Traveller has been offering this style of adventure and educational programs since 1983.

We are also pleased to announce that since 2012, Odyssey Traveller has been awarding $10,000 Equity & Merit Cash Scholarships each year. We award scholarships on the basis of academic performance and demonstrated financial need. We award at least one scholarship per year. We’re supported through our educational travel programs, and your participation helps Odyssey Traveller achieve its goals.

For more information on Odyssey Traveller and our educational small group tours, do visit and explore our website. Alternatively, please call or send an email. We’d love to hear from you!

Read more in our articles:

- Queen Victoria’s Britain: The Definitive Guide for Travellers (Part 1 & Part 2)

- Victorian Country Life

- Victorian Women’s Fashion

- Britain: First Industrial Nation

- Exploring Jane Austen’s England

- William Morris’ Kelmscott Manor

Related Tours

23 days

Oct, Apr, SepCanals and Railways in the Industrial Revolution Tour | Tours for Seniors in Britain

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of Wales, Scotland & England that traces the history of the journey that is the Industrial revolution. Knowledgeable local guides and your tour leader share their history with you on this escorted tour including Glasgow, London, New Lanark & Manchester, Liverpool and the Lake district.

From A$17,860 AUD

View Tour

22 days

AugDiscovering the art and literature of England: Jane Austen, Shakespeare, and more

Visiting England

Stratford upon Avon, Shakespeares birthplace and Anne Hathaway's cottage as well as the Lake district a UNESCO World site and Dicken's London are part of guided tour for a small group tour of like minded people learning about the art and literature of England. Your tour leader and local guides share day tour itineraries to create a unique travel experience.

From A$17,765 AUD

View Tour

21 days

Sep, JunQueen Victoria's Great Britain: a small group tour

Visiting England, Scotland

A small group tour of England that explores the history of Victorian Britain. This escorted tour spends time knowledgeable local guides with travellers in key destinations in England and Scotland that shaped the British isles in this period including a collection of UNESCO world heritage locations.

From A$15,880 AUD

View Tour

From A$13,915 AUD

View Tour